Why did the Soviet Union fight in the Spanish Civil War?

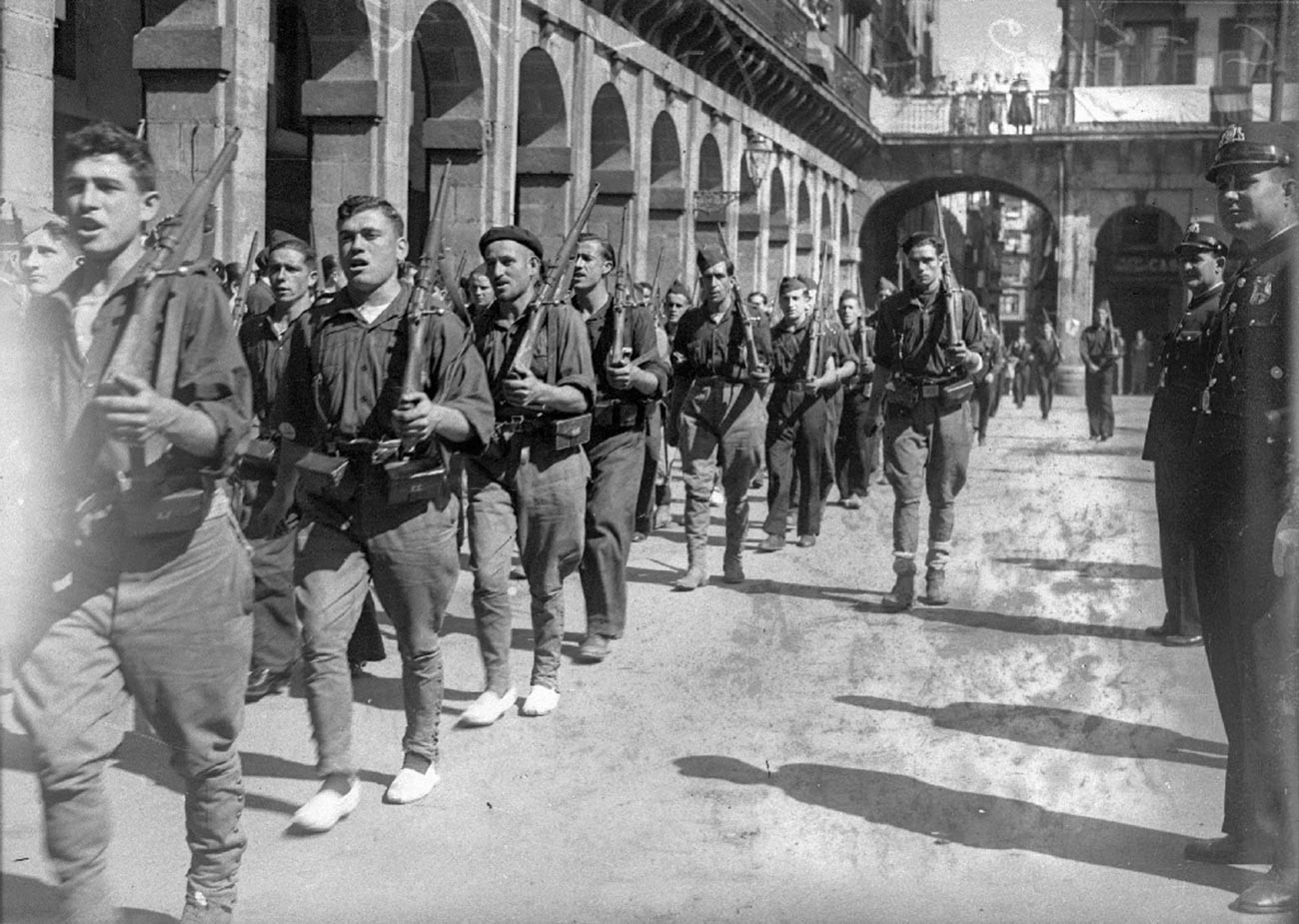

International brigade soldiers with a Soviet Russian machine gun during the Spanish Civil War.

Photo 12/Universal Images Group/Getty ImagesThe civil war that broke out in Spain in July 1936 turned into a kind of rehearsal for WWII. It was there on the Iberian Peninsula that Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy first clashed on the battlefield with the Soviet Union.

Despite repeated requests from Spain's Popular Front-led government for military assistance, the USSR had no intention of intervening in the conflict in far-flung Spain, preferring to remain neutral. But following the abject failure of the Non-Interference Committee, set up by a group of European countries with the aim of avoiding any escalation or expansion of the civil conflict in the Pyrenees, the emboldened Germans and Italians became increasingly involved, obliging the Soviet Union to act.

Street fights in Madrid, 1936.

The Russian State Military ArchiveMoscow’s aims in providing military support to the Second Spanish Republic were to prevent the victory of the pro-German forces of Francisco Franco's nationalists, thus curbing the influence of the Third Reich, and to engage with the Western powers on an anti-fascist footing. The latter objective had to be abandoned almost immediately, since the British and French distanced themselves from the conflict early on and imposed an embargo on the supply of weapons to the warring parties.

Francisco Franco.

Public DomainThe first ship loaded with Soviet weapons arrived at the port of Cartagena on Oct. 12, 1936. Throughout the war, a total of 66 vessels delivering Soviet military equipment, small arms, ammunition and other materiel to Spain docked in the Republic-controlled ports. The Popular Front government decided for itself what weapons it needed, and paid for them in cash courtesy of Soviet loans as well the country's gold reserves, part of which was transferred to the Soviet Union in the first months of the conflict.

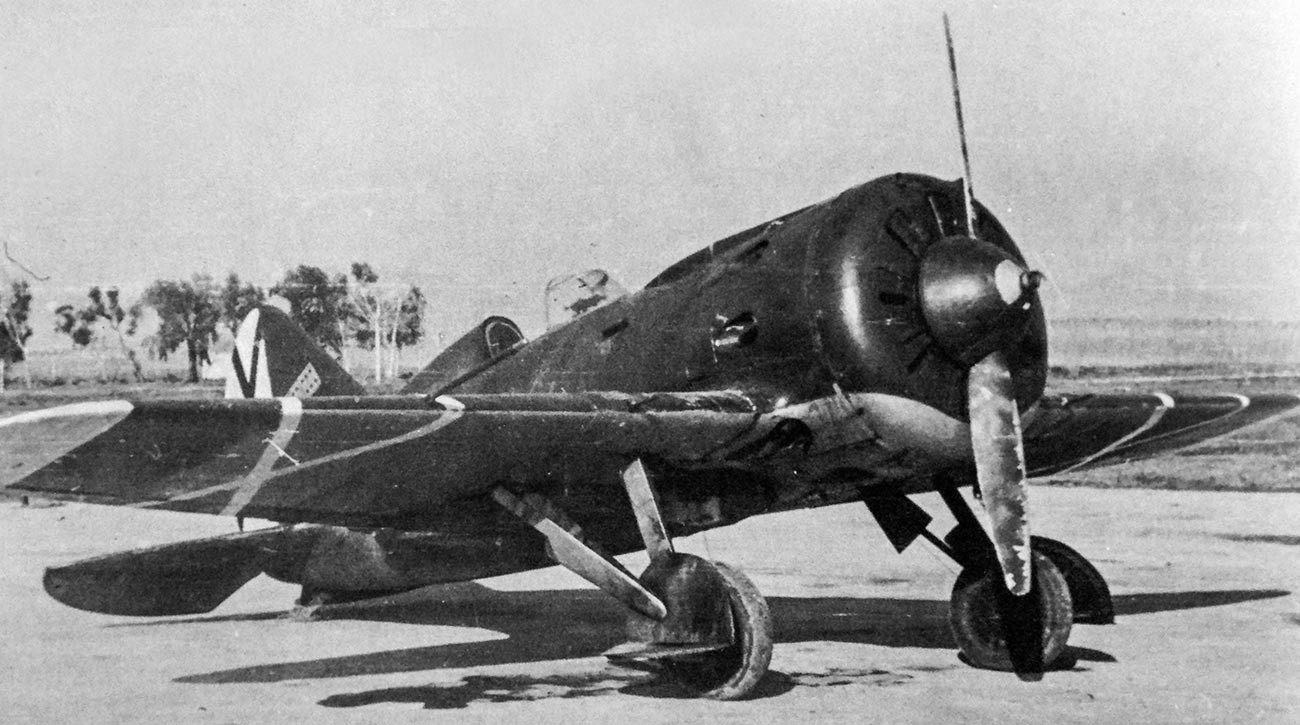

Polikarpov I-16 fighter in Spain.

Photo 12/Universal Images Group/Getty ImagesDuring the three-year civil war, Moscow supplied to the Popular Front and its supporters 648 aircraft (I-15 and I-16 fighters, SB bombers, etc.), 347 tanks (mainly T-26), 60 armored vehicles, over 1,100 artillery pieces, 340 mortars, 20,000 machine guns, almost 500,000 rifles, 862 million rounds of ammunition, 3.5 million shells, and more besides. As the Republic's Minister of the Navy and Air Force Indalecio Prieto noted in January 1937: "The Soviet Union is the only country in the world (besides Mexico) to have provided armed support to the Spanish Republic, all it could, without fuss or fanfare..."

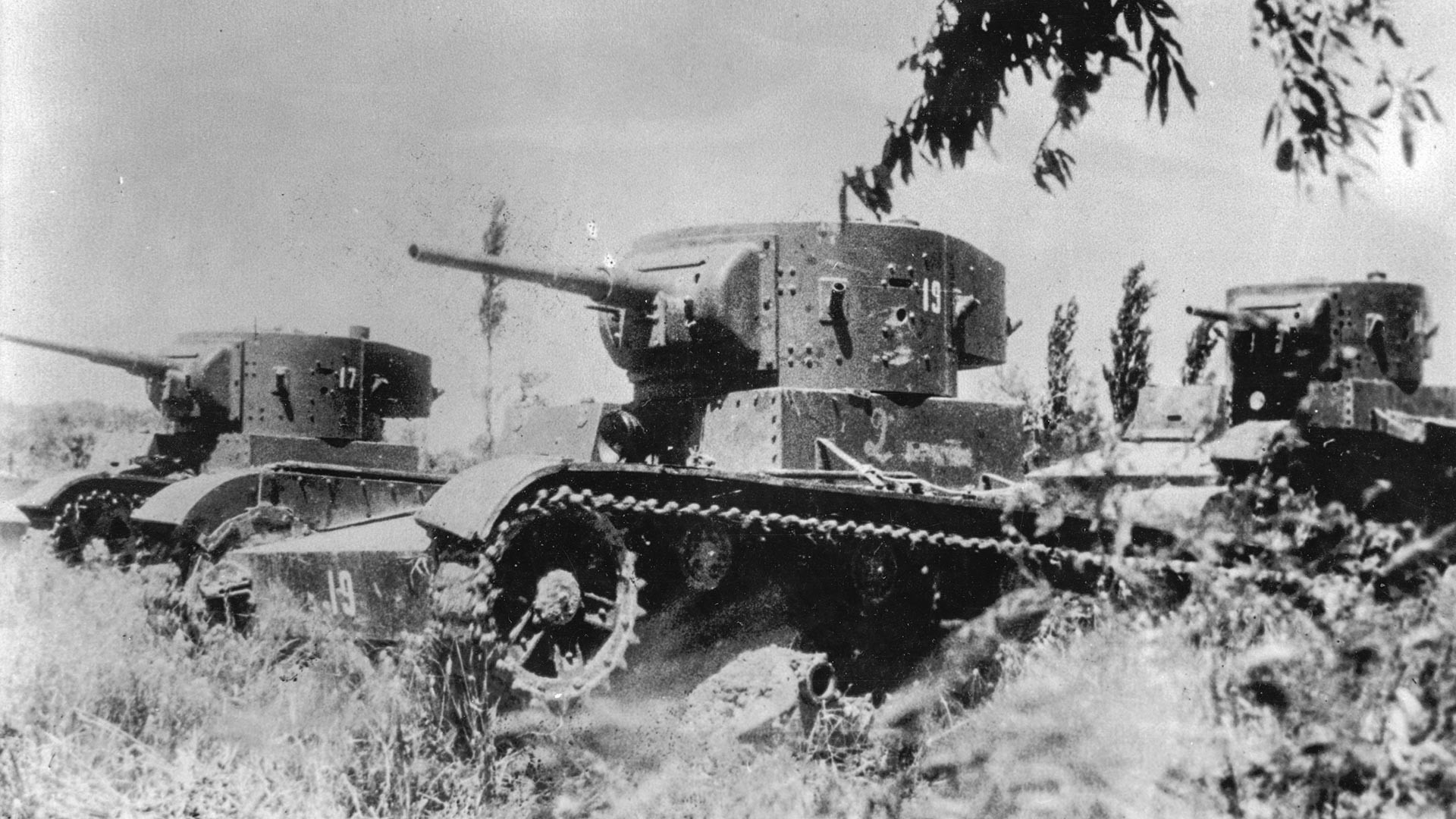

Soviet T-26 tanks in Spain.

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesIn addition to weapons, Moscow sent military advisers and specialists to help the Spaniards, including pilots, tank crews, sailors, signal operators, anti-aircraft gunners, military engineers and interpreters. Their task was to ready and train the Republican armed forces, but many themselves had to take part in the battles.

Soviet pilots near Madrid.

Sputnik“To Spain we sent both young and inexperienced operatives as well as experienced and professional instructors. The country became a kind of training ground for trial-running our future military intelligence ops. Many of Soviet intelligence's subsequent moves relied on contacts established in Spain and conclusions drawn from our Spanish experience,” wrote Pavel Sudoplatov, one of the top Soviet intelligence officers and saboteurs.

The 14th International Brigade.

The Russian State ArchiveGerman and Italian aid to the Nationalists far exceeded that of the Soviets to the Republicans: twice as many planes, almost three times as many tanks, two-and-a-half times as many artillery pieces. The German Condor Legion alone, a volunteer aviation force that accounted for almost half of the Francoists’ air victories during the entire war (314 out of 695), numbered about 5,000 personnel. Mussolini sent a 50,000-strong expeditionary force to Spain, 20,000 of whom were from his personal guard, the so-called Blackshirts. The number of Soviet military personnel did not exceed 2,000, but it was largely thanks to them and the Soviet weaponry that the Republic managed to hold out for so long.

The German Condor Legion.

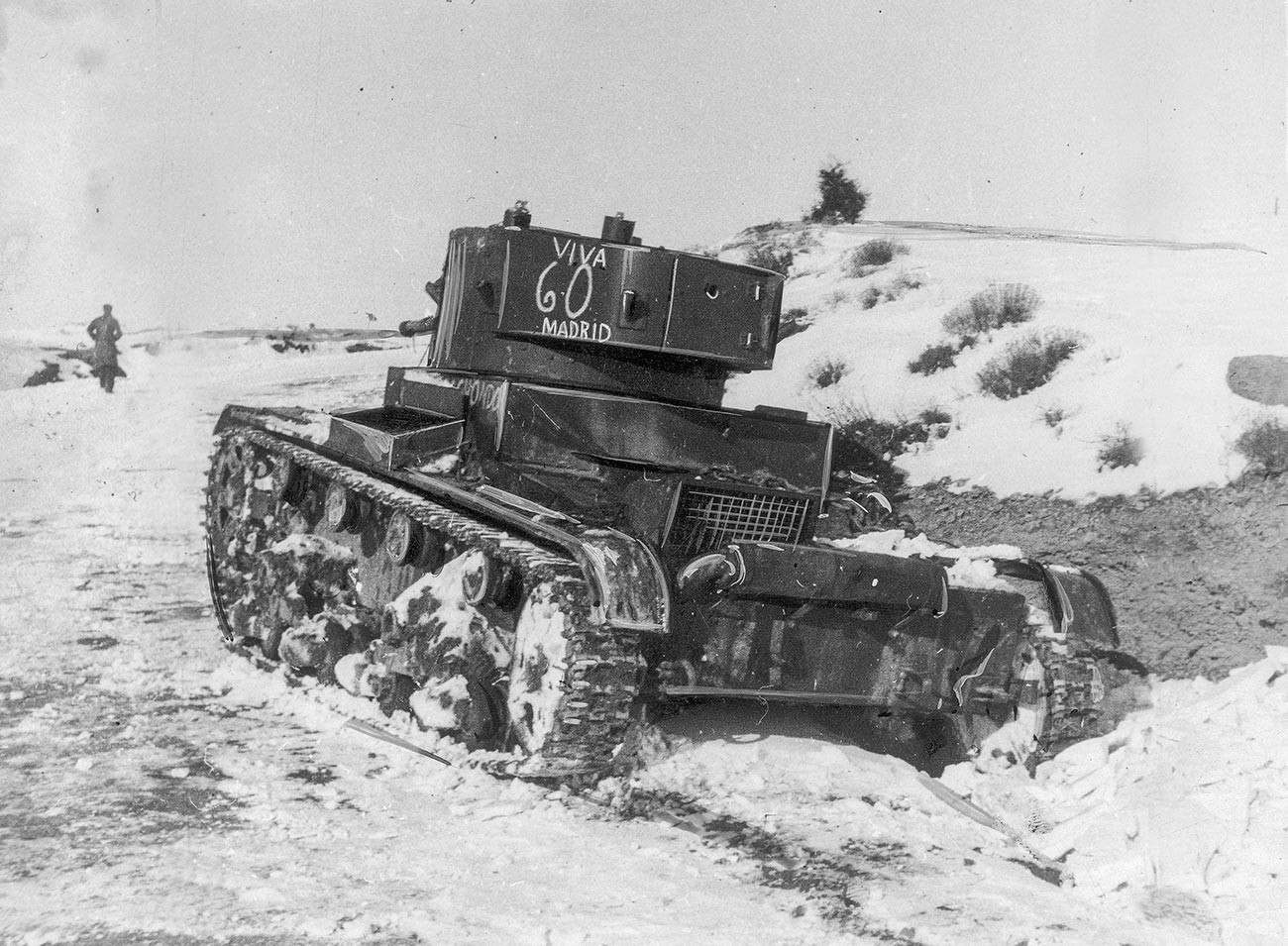

BundesarchivSoviet military advisers and specialists played a vital role in the successful defense of Madrid in the fall of 1936. A notable episode of that battle was the raid on Oct. 29 by Soviet T-26 tanks on the village of Sessinia (30 km from the capital), during which they defeated a squadron of Moroccan cavalry, destroyed a Francoist infantry battalion and inflicted significant damage on their opposite numbers from the Italian tank corps. It was there that the commander of the Soviet tank platoon, Lieutenant Semyon Osadchiy, performed the world's first tank ram, shoving an Italian Ansaldo tankette into a ravine.

Soviet T-26 during the Battle of Teruel.

Public Domain“You should have seen the sudden and drastic change in mood of the Spaniards at the front and in the rear when, in early November, Republican I-15 and I-16 fighters piloted by Soviet volunteers appeared in the skies over Madrid and launched the first air strikes against the rebels. There was no more impunity for the fascist ‘air pirates,’” recalled military adviser Pavel Batov. On top of that, in late October, SB bombers began large-scale bombing of Francoist airfields in Avila, Seville, Salamanca and other cities.

Madrid after the bombing of the city, December 1936.

The Russian State Military ArchiveIn the early period of the war, the SB bombers (or “Katyushas” as the Spaniards called them) were the veritable kings of the Spanish skies. With a top speed of 450 km/h, they were beyond the reach of the Italian Fiat CR.32 and the German Heinkel He 51. In addition to the Battle of Madrid, the SB was actively used in the defense of Guadalajara, the Battle of Jarama and the raids on the Francoist naval base at Palma de Mallorca. Only with the appearance of the German Messerschmitt Bf-109 in the late spring of 1937 was their air superiority challenged.

Tupolev SB in Spain.

Aeronaves del Ala 14 (CC BY-SA 2.0)After the heavy defeats of the Republican army in the spring of 1938, Stalin realized that the Popular Front was on the verge of collapse. Besides, his focus was in any case shifting to central Europe, where the Nazis had annexed Austria in March. The USSR began to gradually curtail its aid to the Republicans, bringing its military advisers and specialists home. Of the nearly 2,000 Soviets sent to Spain, 189 lost their lives. Fifty-nine were awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, some posthumously.

Soviet tanks crews at the tombs of their comrades in Spain.

SputnikMore than 6,000 Spaniards, mostly communists, moved to the Soviet Union after the fall of the Second Spanish Republic. Hundreds of them took part in the war that broke out in 1941 against Nazi Germany, mostly in sabotage units, where their experience of guerrilla warfare proved invaluable. One of the most famous Spaniards in the Red Army was Rubén Ruiz Ibárruri, the son of Dolores Ibárruri, a leader of the communist movement in Spain. Serving as commander of a machine-gun company, he died in the Battle of Stalingrad, and in 1956 was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

Rubén Ruiz Ibárruri with his sister Amaya.

Public DomainThe Francoists dreamed of settling scores with the Russians for their intervention in the Spanish Civil War, and the Wehrmacht's invasion of the USSR gave them that opportunity. The 18,000-strong 250th Spanish Volunteer Division (commonly known as the Blue Division) was sent to the Eastern Front, where it took part in the siege of Leningrad. In October 1943, Franco, seeing which way the tide was turning, recalled the division to Spain. Those who did not want to return joined the SS and continued fighting the Red Army until the fall of Berlin.

Spanish volunteers of the Blue Division in the Soviet Union.

BundesarchivIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox