Did Paul I PREDICT his own death?

Grand Duke Pavel Petrovich, the future Paul I, had many times regretted the “scary story” he told at a friendly dinner in Brussels on June 29, 1782. Paul and Maria Feodorovna were, at the time, traveling through Europe, half incognito – under the names of Count and Countess du Nord.

That evening, after the theater, the Grand Duchess felt tired and went to her room, while Pavel Petrovich remained among a close circle of Brussels high society, of which he was certainly the center that night. The young people began to share “mystical” stories from their lives. Baroness d’Oberkirch, a close friend of the Grand Ducal couple, recalled that the 27-year-old Grand Duke told his own “scary story”. Strolling at night in St Petersburg, he met a tall man in a cloak and hat, his face covered, and a deathly coldness emanating from him. The unknown man walked beside Paul for some time and then, in response to a demand to identify himself, uttered:

“Who am I? Poor Paul, I am the one who takes part in your destiny and who wants you to be especially unattached to this world, because you will not stay in it for long. Live according to the laws of justice and your end will be peaceful. Fear the reproach of conscience; for a noble soul, there is no more sensitive punishment.”

– Do you know what this means, Your Highness? – Prince de Ligne asked.

– It means that I shall die young.

Monk Abel’s fake 'prophecy'

The Voskresensky (Resurrection) Gate of Mikhailovsky Castle

The Voskresensky (Resurrection) Gate of Mikhailovsky Castle

The Mikhailovsky Castle in Saint Petersburg, where Paul I was murdered on the night of March 12, 1801, is the place that supposedly harbors an omen of Paul’s death. In 1800, Emperor Paul allegedly visited a famous soothsayer monk Abel in the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. Answering the tsar’s question about his life span, Abel said: “The number of your years is likened to the number of letters.”

It was believed that “the number of letters” in Abel’s prophecy was the number of letters in the inscription above the main gate of the Voskresensky gates of Mikhailovsky Castle. “Дому твоему подобаетъ святыня господня въ долготу дней” (“Thy house shall be the holy place of God and long shall its days be”) is 47 letters in Old Russian.

There is, however, no documentary evidence – not even letters or memoirs of those years that include this story. Paul didn't live to reach 47 – at the time of his murder, he was 46 years 5 months old. The facts do not add up about monk Abel, as well.

Starting with the fact that, in 1800-1801, monk Abel didn’t live or reside in Alexander Nevsky Lavra, the main monastery of St. Petersburg. In 1796, six months before Paul’s accession to the throne, Abel was interrogated by Alexander Makarov, the chief of the Secret Expedition, the organ of state security, after which he was imprisoned in the Shlisselburg Fortress. But, as soon as Paul ascended the throne, he saw to it that Abel was released and handed over to Gavriil, Metropolitan of Novgorod and St. Petersburg. In the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, Abel was tonsured as a monk (at his own request), but he didn’t stay there.

Mikhailovsky (St. Michael's) Castle in St. Petersburg

Mikhailovsky (St. Michael's) Castle in St. Petersburg

Very soon after the tonsuring, Abel left the Lavra and went to Moscow where, prophesying, he collected money. For this, he was exiled to the Valaam monastery in 1798. In March 1800, a book was found in Abel’s monastic cell “with a sheet found in it, written in Russian letters, but the book is written in an unknown language” according to Ambrosius, Metropolitan of Saint Petersburg, writing to the General Prosecutor Obolyaninov. The case was reported to the tsar and, perhaps enraged by Abel’s behavior, Paul ordered him to be brought to St. Petersburg and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress, which was done on May 26, 1800.

“He seems to be just rambling and his lies mean nothing more; meanwhile, he thinks to draw out something with imaginary prophecies and dreams. Has a restless disposition,” a report on Abel from the fortress states. At the time of the death of Paul I, Abel was still in the fortress. Under Alexander, he was transferred to the Solovetsky monastery.

“Neck turned on the side”

Mikhail Kutuzov

Mikhail Kutuzov

The last dinner of the Emperor in his inner circle was held on the evening of March 11, 1801. It was attended, among other 20 guests, by General Mikhail Kutuzov, whose story is narrated by his assistant Count Langeron: “The emperor was very cheerful and joked a lot... After dinner, the emperor looked at himself in the mirror, which had a defect and made faces look distorted. He laughed about it and said to me, ‘Look how funny the mirror is, I see myself in it with my neck turned on the side.’ That was an hour and a half before he died.”

But what is the “prophecy” here? Possibly, the story hints at the main weapon of the emperor’s assassins, the scarf with which he was strangled.

Ivan Matveyevich Muravyev-Apostol, the tutor of the tsar’s sons Alexander and Konstantin and vice-president of the Foreign Collegium, was also present at the same dinner. He recalled the last conversation between Paul and Kutuzov: “Finally, they talked about death. ‘Going to the other world isn’t sewing pouches’ – were Paul's last words to Kutuzov."

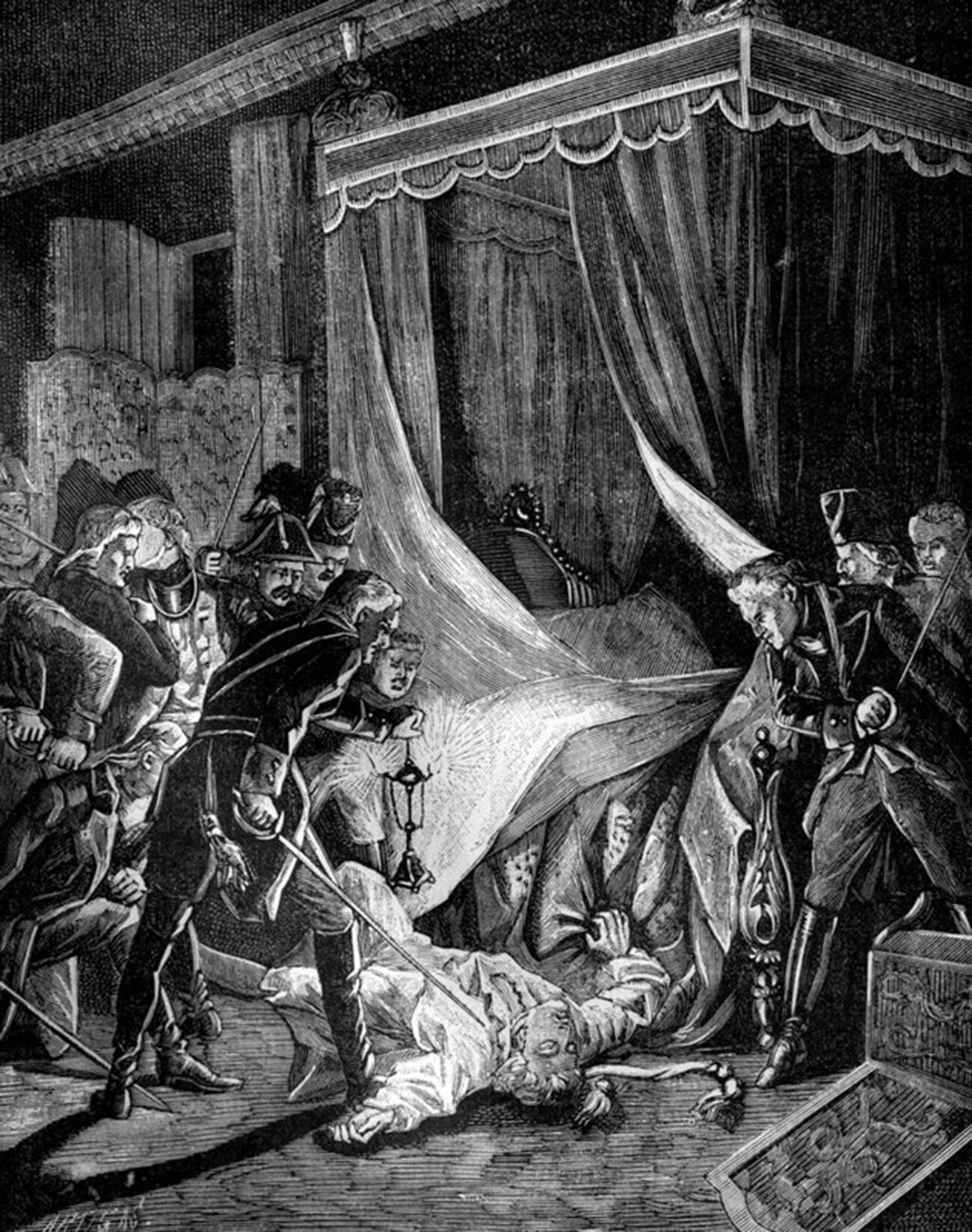

The murder of Tsar Paul I of Russia, March 1801. A print from "La France et les Français à Travers les Siècles", 1882-1884

The murder of Tsar Paul I of Russia, March 1801. A print from "La France et les Français à Travers les Siècles", 1882-1884

Nikolay Shilder, a 19th-century historian, tells about another strange omen, not connected to Paul's death but happened the same evening. Shilder wrote in his biography of Nicholas I about Paul’s last encounter with Nicholas, his son. “In the evening of March 11, Paul walked into Nicholas’s room. The Grand Duke was just four years old. ‘The son asked why his father was called Paul the First.’ – ‘Because there was no other sovereign who bore that name before me,’ the emperor answered. ‘Then I shall be called Nicholas the First’ – ‘If you come to the throne,’ the emperor remarked, kissed his son firmly and quickly withdrew from his room.”

What's the catch in this story? Little Nicholas wasn't meant to be the heir. Alexander, Paul's eldest son and Nicholas's brother, inherited the throne. However, what little Nicholas said that evening eventually came true – he came to the throne in 1825 after Alexander's sudden demise.

“A foolishness, a tale, a folly”

Henriette Louise de Waldner de Freundstein, Baroness of Oberkirch

Henriette Louise de Waldner de Freundstein, Baroness of Oberkirch

But, let’s return to the first “prophecy”, told by Pavel Petrovitch himself at a dinner in Brussels. With this story, Paul launched a meme about himself that lives to this day – that he himself believed in his “scary story”. However, the same Baroness d’Oberkirch further writes in her memoirs that Paul, at a dinner in Amsterdam, said to her: “I’ve had you there nicely, didn’t I? The more fascinating the story was, the more fascinating it is that you took it seriously.”

When the baroness asked if Paul had really invented this “fable, which he told to… scare us a little”, the Grand Duke only insisted: “This was no adventure, can’t you understand, it is a foolishness, a tale, a folly, told to amuse you, at least do not believe in it in any way.” Pavel Petrovich, according to the Baroness, was angry with himself for telling this story. “But let me, gentlemen, ask you all to keep my story a secret, because it would be very unpleasant if the story of the ghost in which I play a part was to spread all over Europe,” said Pavel.

Emperor Paul I of Russia

Emperor Paul I of Russia

The fact that the Baroness herself devoted so much space in her memoirs to this tale and gave a dramatic coloring to it can also be explained. The Baroness herself, Henriette Luisa de Waldner de Freundstein, lived only two years longer than Paul: she, too, died young, aged 48, and she wrote her memoirs in her final years, already knowing of the Emperor’s death. As we see, the Baroness did not keep the promise she gave Paul at that dinner in Brussels.