For most Soviet citizens, international tourism was a once in a lifetime experience. Those who were lucky to get on a tour abroad often dived head-on into troubles.

International tourism first became available in the USSR in the early 1930s, when the state organization responsible for sending Soviet people on foreign trips, Sovtour, was formed. However, as the country under the dictatorship of Joseph Stalin was isolating itself further and further from the rest of the world, ‘Sovtour’ did not perform particularly well, limiting its operations to just a solitary cruise.

The Khrushchev Thaw - the period when repression and censorship in the Soviet Union were relaxed - lifted severe restrictions on international tourism for the Soviet people. Starting from the mid-1950s, every Soviet citizen could theoretically go on a tour abroad. However, in practice it was a whole different thing for ordinary people.

To get permission to travel abroad, a potential candidate needed references from work that highlighted their impeccable morality. Potential tourists had to appear, at least on paper, as dedicated communists and modest, but politically active individuals.

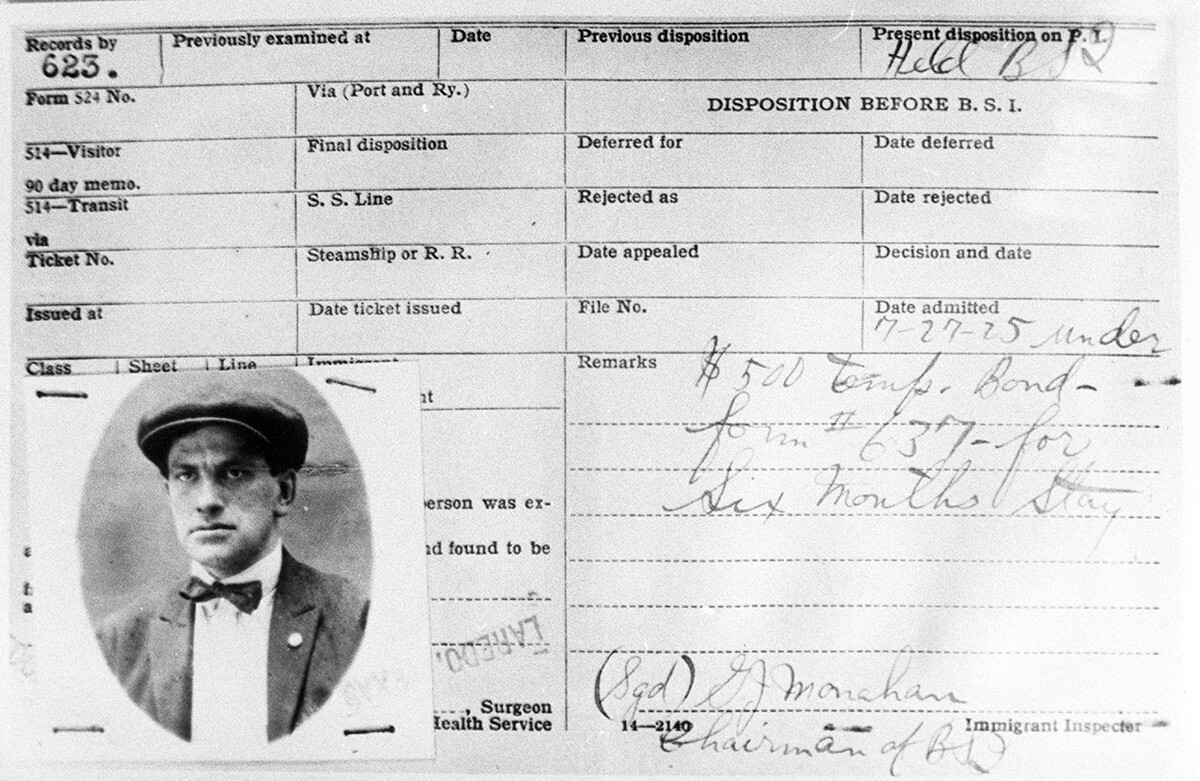

The passport of Soviet poet Vladimir Mayakovsky.

V. Khomenko/SputnikReference letters were then evaluated by different bureaucratic institutions of the Soviet Union before they finally landed on a table in Lubyanka, where the candidate was eventually approved by the KGB.

“There was a special system of various briefings, during which a person had to sign a written form where he promised he would not disclose information [about life in the USSR] and also had to familiarize himself with a certain set of rules. In addition, the potential tourist had to pass some sort of examination. For example, if one was going to East Germany, one had to name the chairman of the German Communist Party,” said historian Igor Orlov in an interview.

In practice, the procedure for getting permission to travel abroad was so broad and elaborate that it opened room for arbitrary decisions and corruption. Those who were lucky enough to receive permission from the authorities had to sort out the money issue.

While costs of tours varied depending on the destination, most of the tours available for the Soviet citizens started from 150 rubles, some 50-100 rubles more than an average monthly salary in the USSR in the 1960s.

USSR. July 1, 1958. An employee of Aeroflot answers a phone call.

TASSGeopolitics played a major role in shaping the most common travel destinations of Soviet tourists. The vast majority of foreign tours for Soviet citizens were to Czechoslovakia, East Germany and Socialist Republic of Romania.

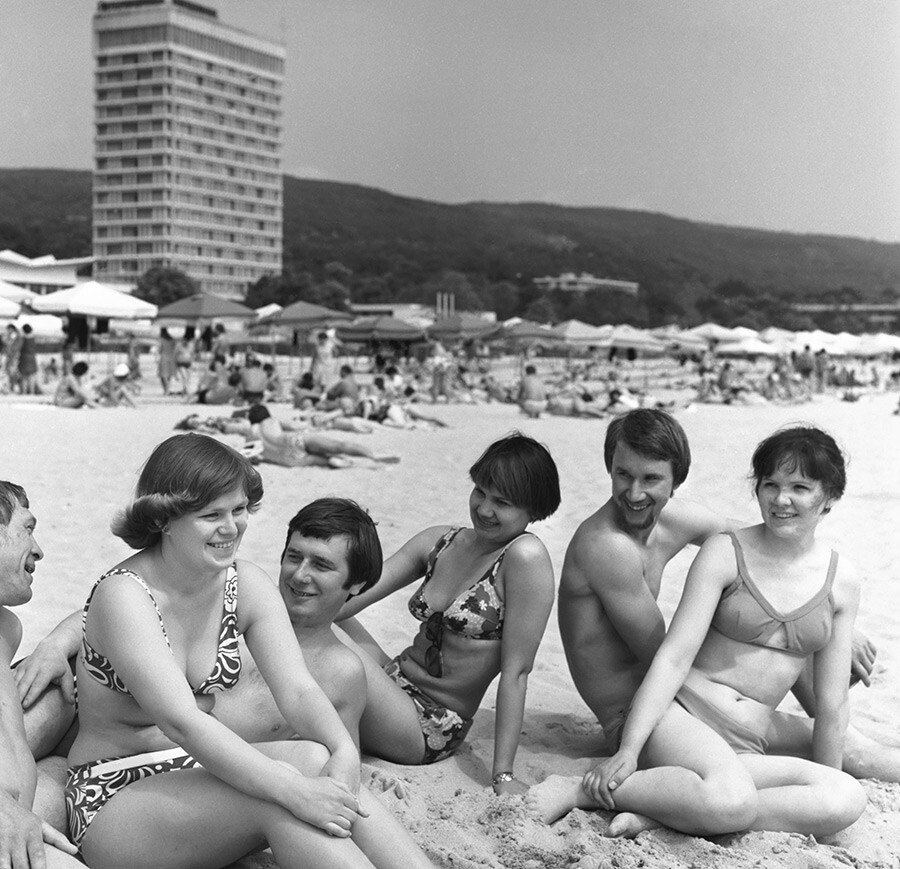

The growing popularity of Bulgaria as a vacation destination for the Soviet tourists eventually translated into a common saying: “A man is not a bird, Bulgaria is not abroad.”

June 1-10, 1977. Golden Sands, People's Republic of Bulgaria. Tourists from Leningrad and Chelyabinsk rest on the beach of the International Hotel.

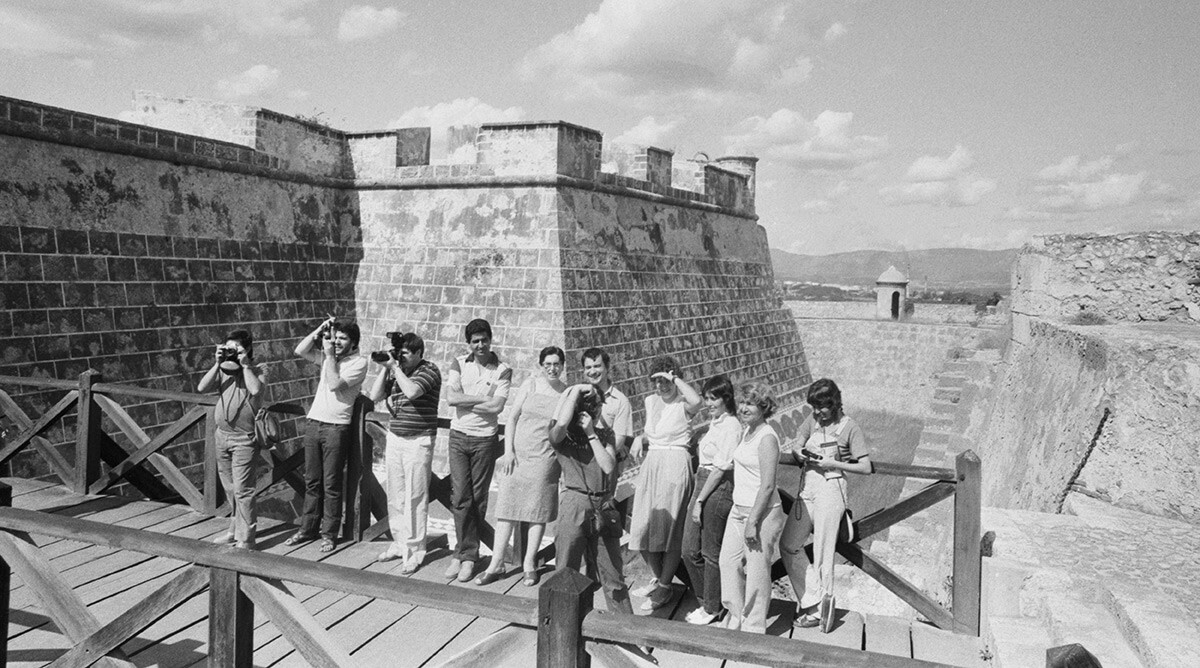

Valentin Mastyukov/TASSThe Cuban revolution opened up a more exotic destination for the Soviets. India, a non-aligned nation that proclaimed its neutrality during the Cold War, but, nevertheless, had good relations with the Soviet Union, provided another vacation spot for Soviets. Sometimes, tours to Finland, Italy, North Korea, Japan, Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and even Mexico were organized in the 1960s.

December 1, 1983. Republic of Cuba. Santiago de Cuba. December 1, 1983. The old fortress of El Morro.

Semyon Maisterman/TASSHowever, the more exotic the destination, the more expensive the tour was. If a trip to Bulgaria could cost some 150 rubles, a cruise with stops in multiple countries in Europe or Africa could cost a whopping 900 rubles — an equivalent of a five-month salary for a middle-class Soviet worker.

Although a workplace or a factory could potentially cover a part of expenses, this privilege was often reserved for well-connected individuals. Common Soviet citizens had to save a lot to afford trips like this.

There was also a limit on how much local currency a Soviet tourist could purchase. For example, those few Soviet citizens who traveled to the U.S. in 1961 were only allowed to purchase a total of 31.90 U.S. Dollars (or $2.30 per every day of stay in the country).

U.S. dollars. 1989.

A. Babushkin/TASSSince it was not enough to buy things that were scarce in the USSR, some Soviet tourists intentionally brought extra items of value, like photo cameras or bottles of vodka, abroad to sell them and fetch some extra cash.

Soviet citizens always went abroad in organized groups. Before departure, heads of groups were selected based on their reputation and party affiliation. Heads were responsible for monitoring the behavior of the group members, reporting incidents and writing final reports after tourists had returned to the Soviet Union.

In addition, Soviet tourist groups were often accompanied by one or two KGB agents, whose job was to make sure the trip went smoothly and did not cast a shadow on the USSR’s reputation and interests.

Sometimes, while abroad, Soviet tourists faced so many new temptations that it was hardly possible to restrain them, despite all the preparation.

“...without my permission as a group leader, albeit in their free time, P. and H. went to a strip club together, even though tickets for striptease are quite expensive, from 35 to 50 dinars,” read one of the reports.

Members of the Soviet army dance troupe seen taking photographs in the park at Versailles, just outside Paris.

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesStrip clubs, illegal currency exchange and trading, bars, alcohol-infused brawls and other mischievous behavior was an integral part of Soviet tours abroad. One of the most reviled behavior, however, was a fleeting encounter with a foreigner. Such incidents often caused scandals and ended up in the final reports.

“Women comprised 80 percent of [all members of Soviet] tourist groups going to Bulgaria. They would arrive, meet the local men and disappear for the night. It was a shock to the heads of the delegations when the girls did not return to their hotels for days. As the fugitives later explained, they spent the whole night ‘collecting seashells by the sea on the beach’. It went so far that the leaders of tour groups would lock the girls up and put a ‘sentry’ at the door to make sure they didn’t go anywhere at night,” says historian Igor Orlov.

July 1, 1958. Aircraft coming in for a landing.

TASSForeign tours were a hard-earned privilege for Soviet people throughout most of the Soviet Union’s existence. It was only in 1991, after the USSR’s collapse, when Russian people were free to travel abroad as they pleased.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox