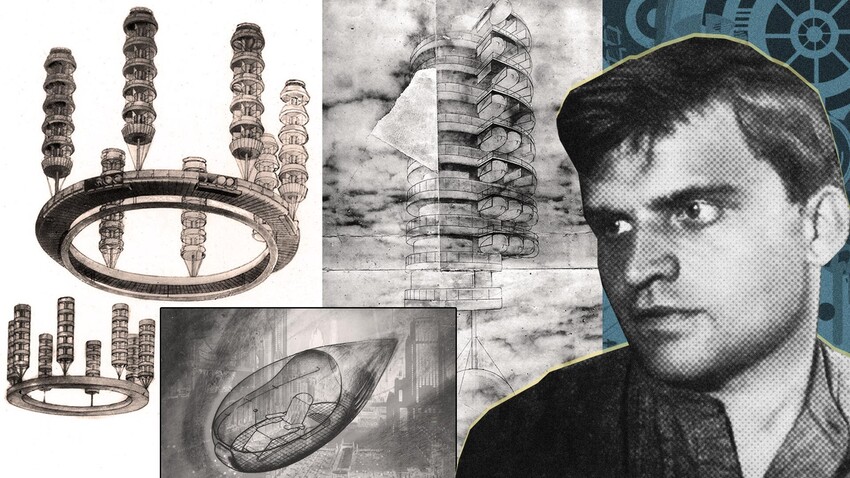

In 1928, a graduate of the Higher Art and Technical Institute in St. Petersburg was preparing to defend his diploma thesis. His presentation became the first theoretical step toward human migration into earth’s orbit.

Georgy Krutikov started his scientific endeavor with a simple idea: each type of society should have a unique design of cities. For example, feudal societies tend to build their cities around fortresses and arrange them in a circular shape while capitalist societies tend to arrange the streets of the cities in a rectangular manner.

Georgy Krutikov.

Public domainKrutikov argued that the new communist society deserved to have its own unique urban arrangement. In his thesis, he offered his vision of the flying city designed to become mainstream in the USSR of the future. His work made quite a splash at the time.

The architect proposed to vacate the earth, leaving only factories and other production facilities on the surface, and permanently relocate humans to communal cities floating in the air.

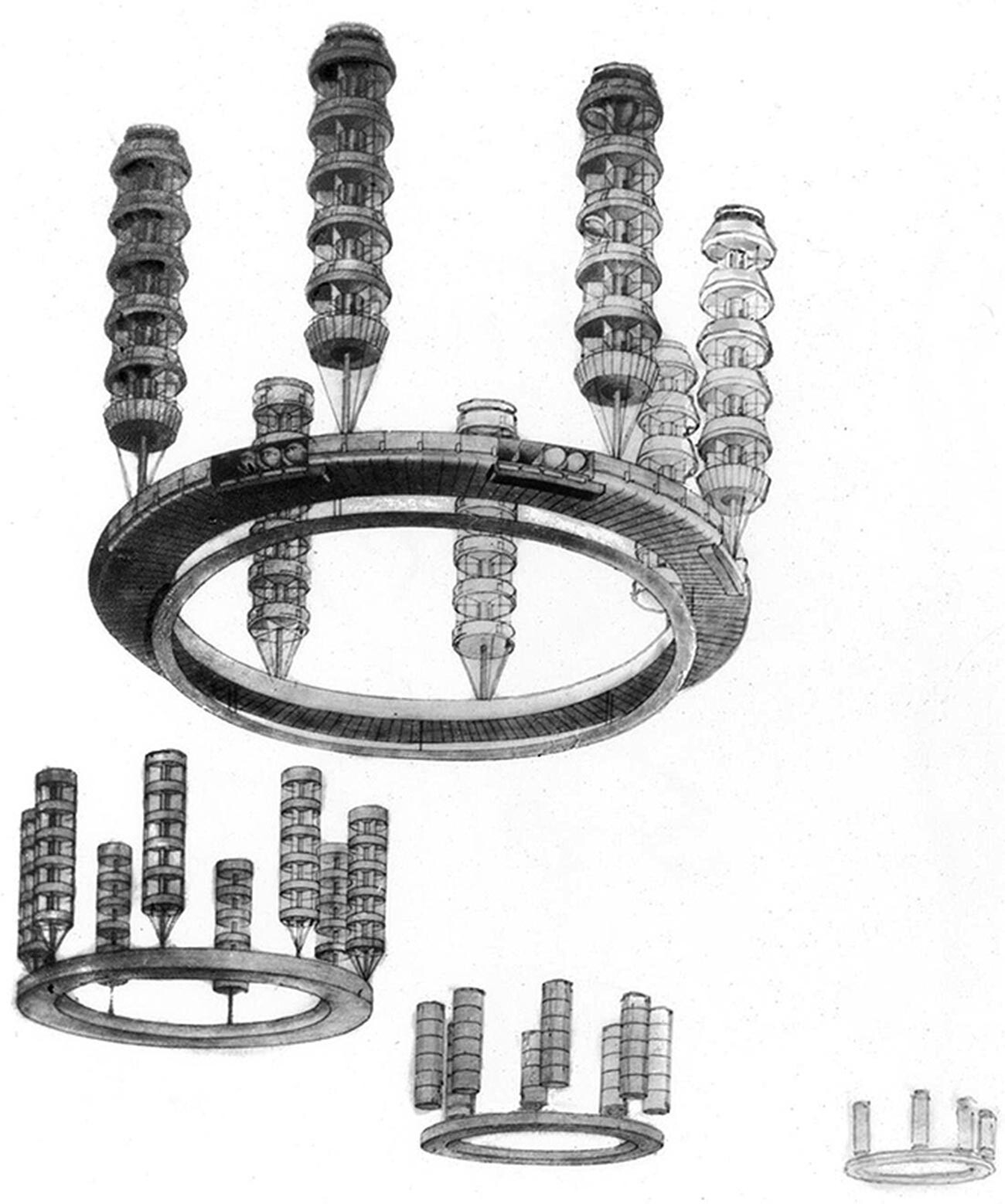

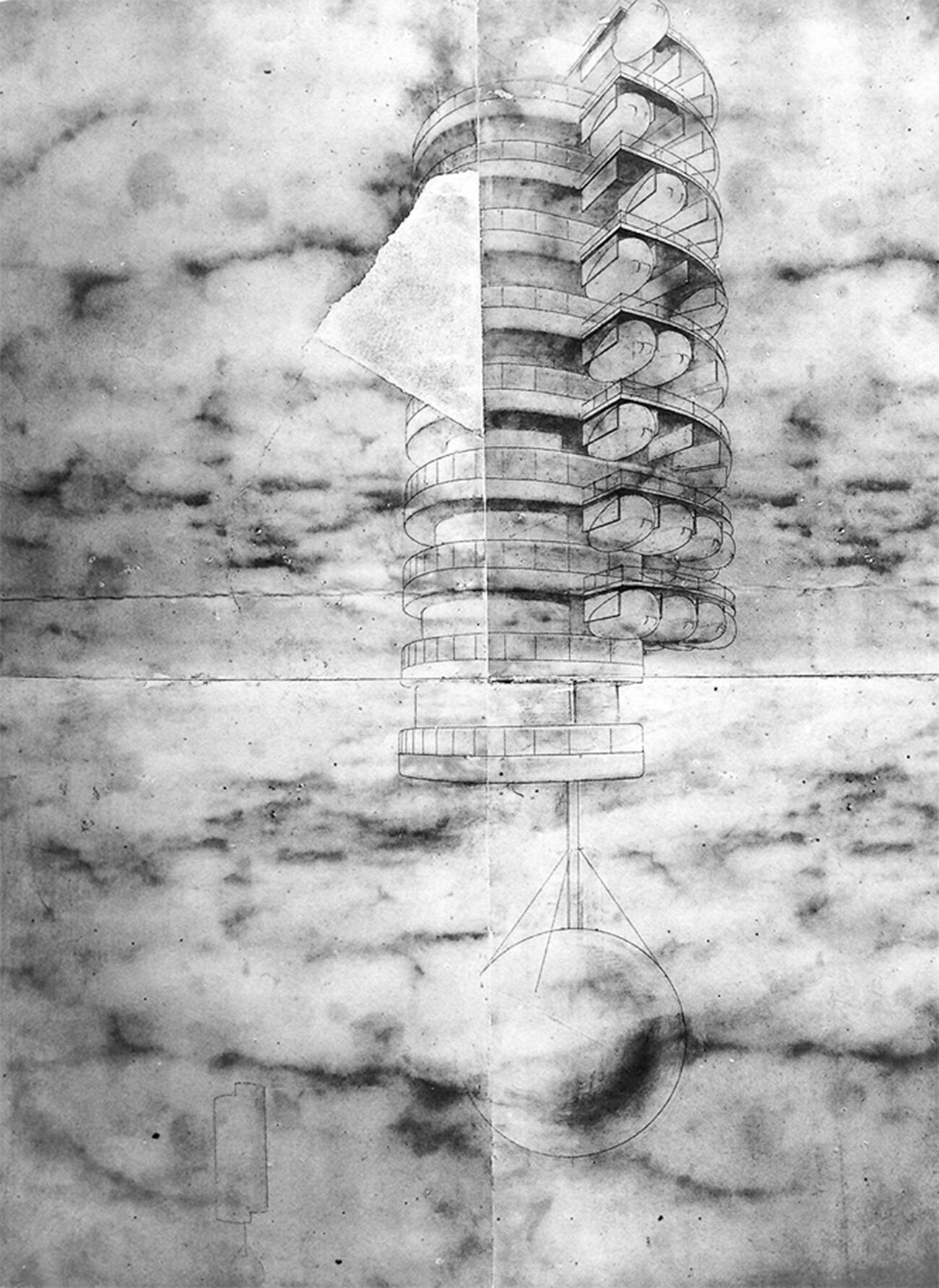

The picture above shows the general vision Georgy Krutikov had of the new city. The habitable high-rise buildings stand in a circle on a ring-shaped platform where, according to the architect’s plan, utility rooms and technical facilities were to be located.

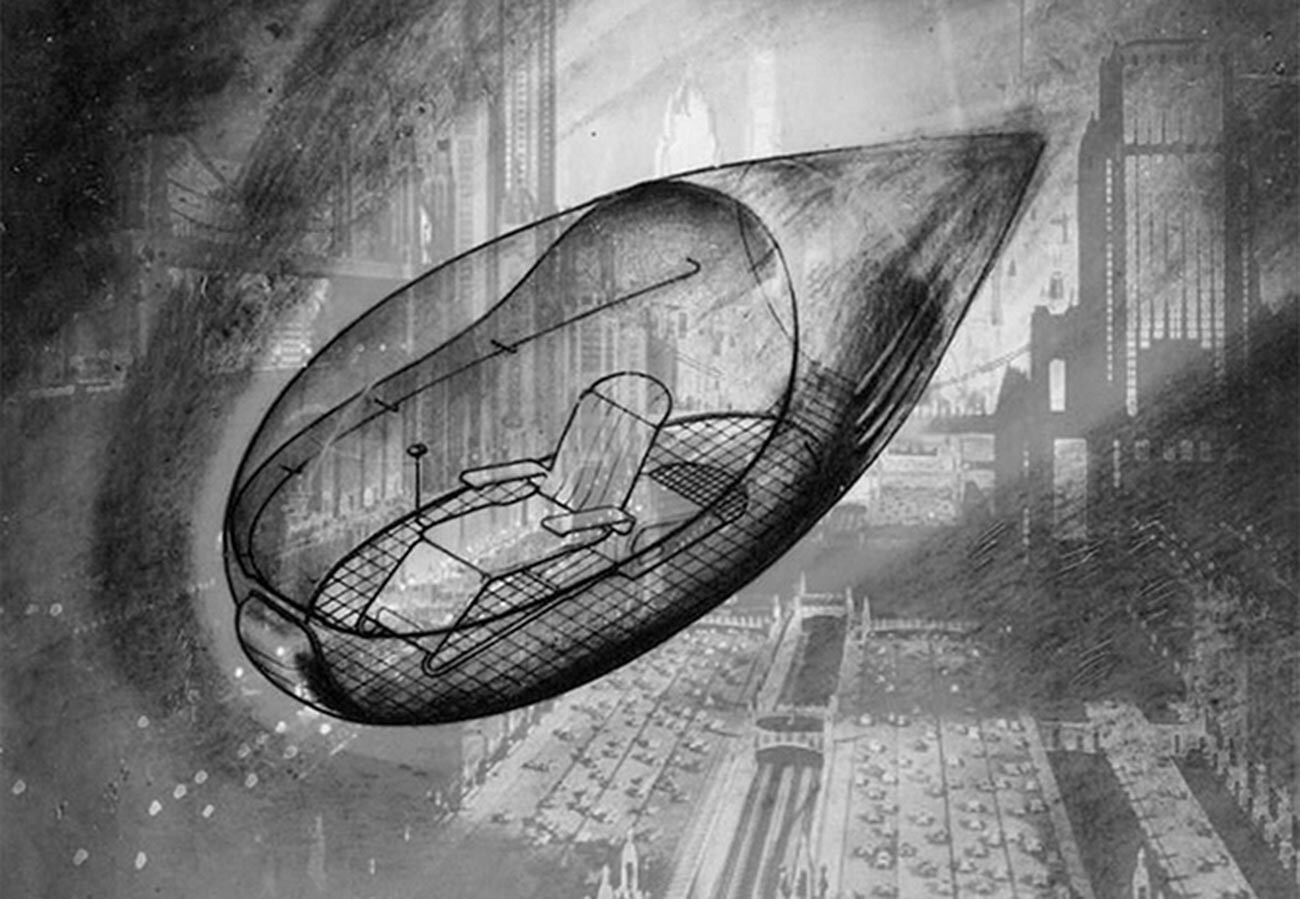

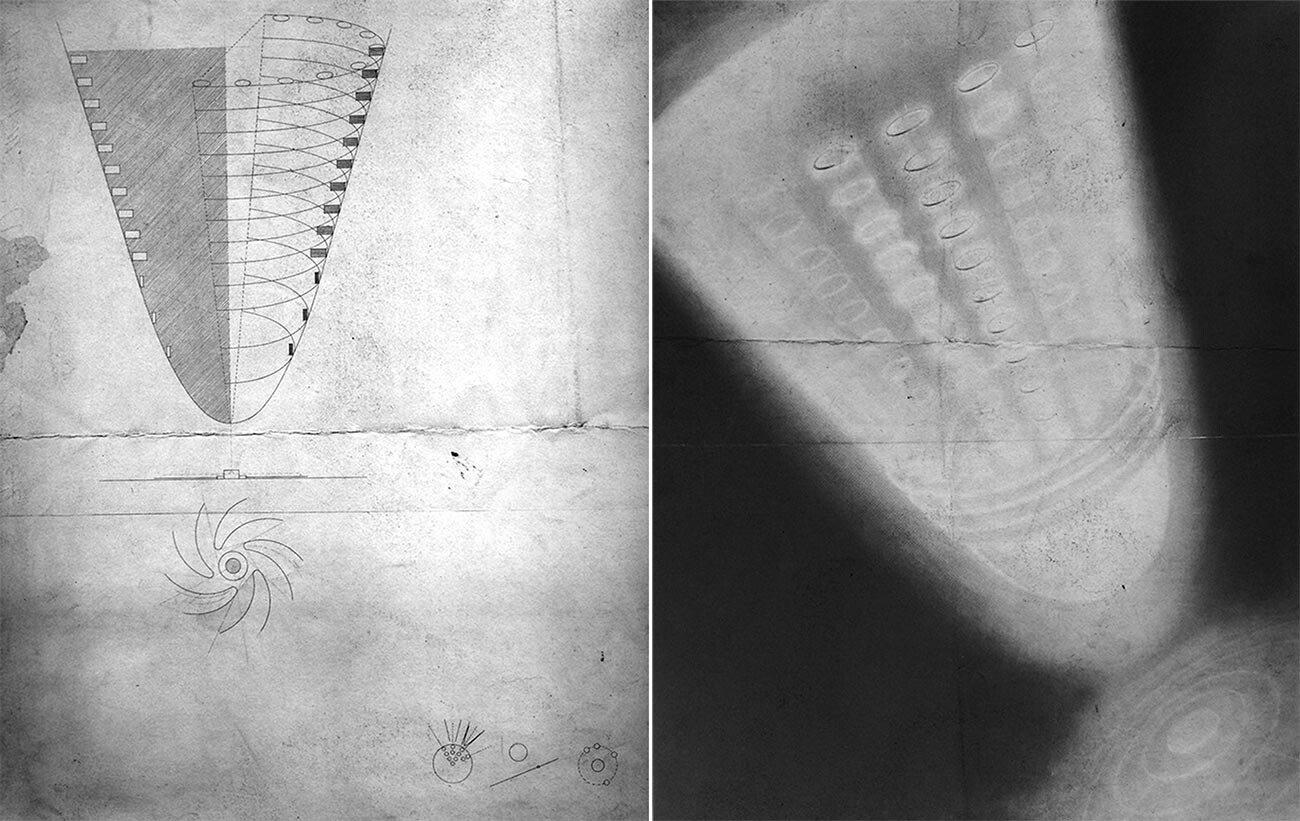

The architect proposed to use small self-sufficient flying cabins – somewhat similar to the flying vehicles featured in Universal Pictures’ blockbuster ‘Oblivion’ (2013) – to transport humans from the surface of the earth to the flying city and back.

Contrary to the popular movie, however, Krutikov’s flying cabins were designed to also be used as short-term housing, an autonomous part of bigger stationary buildings.

The cabins had a streamlined shape. It was assumed they would be filled with transformable furniture that would change according to the circumstances and necessities of the pilot. The cabins would also be able to dock with the main dwelling, according to Krutikov’s plan.

Besides architecture, Krutikov was fascinated with zeppelins. He believed that, in the immediate future, the scientists would discover or invent new forms of energy, making Krutikov’s “flying city” a reality.

Therefore, Krutikov believed that the implementation of his futuristic plan was a matter of the near future.

Proponents of Krutikov’s work considered the project a significant step in the architectural avant-garde. However, opponents criticized it as being excessively fantastic and unrealistic.

Despite the criticism, Krutikov successfully defended his work before a panel of academicians and received a professional degree. He built his future career in architecture, although his new projects were more realistic than the “flying city”. For example, Krutikov successfully designed administrative and residential buildings in Moscow.

The architect and visioneer died in March 1958. His brainchild never became a reality.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox