‘The Meeting Place Cannot Be Changed’ (1979).

State Committee of Television and Radio Broadcasting of the Soviet Union / Odessa Film StudioStrong, courageous, honorable and delicate knights in shining armor - that is how Soviet citizens perceived law enforcement officers. The state went to great lengths to create an ideal public image of the police, even though the reality was somewhat different.

Soviet police cadets in Saratov, 1971.

TASSUp until the mid-1950s, nobody in the USSR cared about popularizing the police service. Being “rough and dirty”, it was never surrounded by an aura of romanticism like, for example, the Soviet intelligence agencies. Nor had the involvement of the police in recent political repressions been erased from people’s memory.

At the Moscow police department, 1950.

Anatoly Garanin / SputnikHowever, with the beginning of liberalization of political and public life during the so-called ‘Khrushchev Thaw’, which began soon after Stalin’s death, state agencies began to strive for greater openness. This resulted in the “humanization” of police officers in public opinion. Newspapers and magazines published articles depicting police officers as ordinary people who, in their spare time, painted and played music, sang in a choir and planted flowers.

Soviet police in 1952.

Robert Diament/МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruThe task of improving the reputation of the police was partially delegated by the state to the creative intelligentsia. In 1954, poet and writer Sergei Mikhalkov wrote a poem called ‘Uncle Styopa the Policeman’, which created an iconic image of a tall policeman, who skillfully rescued citizens from all kinds of trouble.

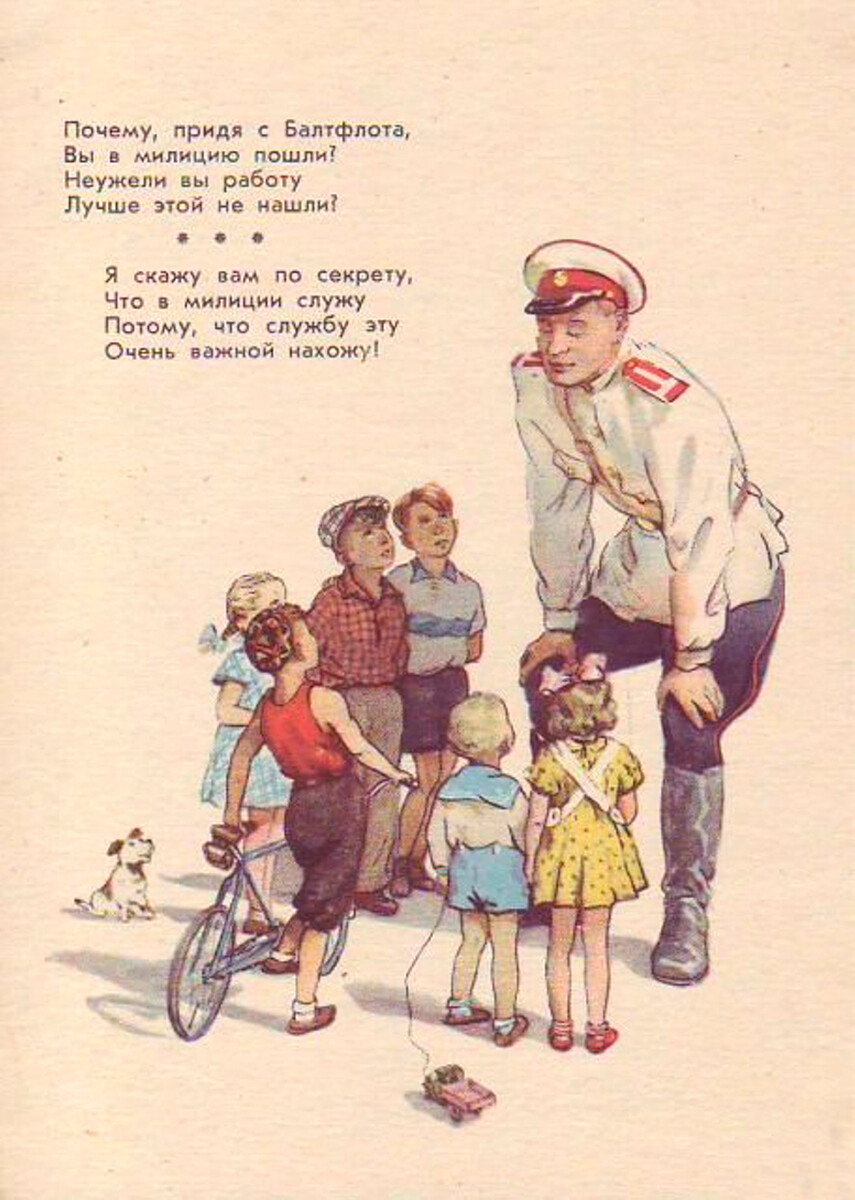

Illustration to the poem ‘Uncle Styopa the Policeman’.

Public DomainThe detective genre was revived in the Soviet Union with the publication in 1956 of Arkady Adamov’s novella called ‘The Motley Case’. The author fully immersed himself in the world of the Moscow police. He even went on detentions and took part in ambushes. A movie based on the book was filmed two years later and marked the beginning of a whole universe of movies about courageous defenders of law and order. Among these, the most popular were: ‘Come Here, Mukhtar!’ (1965), about the adventures of a police lieutenant and his faithful dog, as well as the trilogy about a kind and clever village policeman named Fyodor Aniskin.

‘Come Here, Mukhtar!’ (1965).

SputnikThe real heyday of Soviet police came in the late 1960s and 1970s, when Nikolai Anisimovich Schelokov became the head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Under his management, employees received a noticeable increase in wages and many benefits. Officers began to be actively provided with housing. The number of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs educational institutions grew across the country, which attracted young people en masse. “He worked tremendously hard, especially in the early years, when he deeply studied the roots of crime across the country. Under him, the internal affairs agencies became more respected by the people,” Shchelokov’s deputy Yuri Churbanov wrote.

Nikolai Schelokov.

Aleksander Morozov / SputnikDue to Nikolai Shchelokov’s efforts, numerous books, films and television series were devoted to the everyday life of the Soviet police. The professional holiday of the Soviet police began to be celebrated annually on November 10 with a grand concert and was about as popular as the New Year’s celebrations at the time.

Celebration of the professional holiday of the Soviet police, 1969.

SputnikThe TV series ‘Investigation Led by Experts’ (1971-1989) and the movie ‘The Meeting Place Cannot Be Changed’ (1979) became real cult phenomena. Thousands of letters from all over the country flooded the editorial office of the “Experts” requesting for help with investigating unsolved cases. “Trust in the characters was so strong that many people thought that theater was a hobby for us, and that we actually worked for the police,” recalled Leonid Kanevsky, who performed one of the roles.

‘Investigation Led by Experts’ (1971-1989).

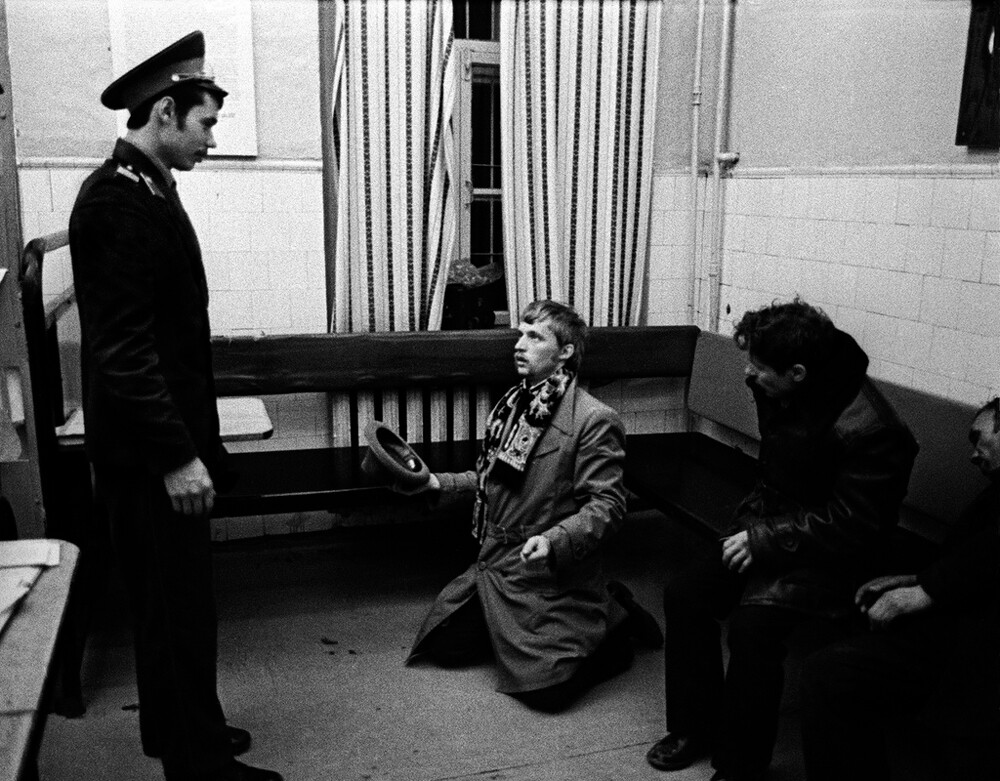

Soviet Central TelevisionOn a late evening of December 26, 1980, police officers on duty at the Zhdanovskaya station of the Moscow Metro (present-day Vykhino) detained and severely beat a drunken KGB major. The major died at the hospital several days later. In response, the Committee, along with the Prosecutor General’s Office, literally “shook up” the entire Ministry of Internal Affairs, uncovering a myriad of shocking cases of power abuse by the police across the country, including robbery and murder of drunken passengers on the metro. The investigations did not spare the all-powerful minister himself. After being accused of corruption and fired, Shchelokov shot himself in 1984.

At the Kazan police department, 1978.

Rustam Mukhametzyanov/russiainphoto.ruFor a long time after the Zhdanovskaya incident, people were still wary of police officers on duty at metro stations. The closer the country progressed towards its decline, the more such ugly episodes of police activity came to light and the lower became the long-held prestige of the police.

At the shooting range, 1987.

Igor UtkinAfter the collapse of the Soviet Union during the “lawless” 1990s, the image of a police officer in popular culture became completely different. It was no longer a knight in shining armor but, at best, a broken down, but honest officer who, amid general chaos and corruption, stubbornly fulfilled his duty. Now, policemen were competing for viewers’ attention with the new heroes of book novels and television series - the criminals.

Traffic police in Orenburg, 1989.

Valery Bushukhin/TASSDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox