“The Chukchi people are strong, tall, audacious, broad-shouldered, sturdily built, level-headed, fair-minded and bellicose; they love freedom, can’t stand dishonesty and are vengeful; and, in time of war, when they end up in a dangerous situation, they kill themselves,” was how Russian officer Dmitry Pavlutsky described the indigenous people of the Chukotka Peninsula on the eastern edge of Eurasia which Russia began to colonize in the middle of the 17th century.

Few peoples living east of the Ural Mountains resisted the Russians as much as the Chukchi. Refusing to become subjects of the tsar and pay yasak (tribute), they waged bloody wars against the newcomers for almost a hundred and fifty years, destroying their settlements and successfully ambushing their military detachments.

A Chukchi familiy in front of their home near the Bering Strait.

ictures From History/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesFor the Russian troops (mainly Cossacks), bringing the nomadic reindeer herders to submission proved an extremely difficult task owing to the peninsula’s harsh climate and its remoteness from the center of the Russian state, as well as limited human resources. A not insignificant factor in their frequent failures was the fact that the Chukchi were among the most ferocious and skillful warriors in all of Siberia and the Far East.

Physical strength and endurance were valued above all else in Chukchi society. From an early age, the future reindeer herders and hunters were taught to build a strong physique, readily endure hunger and sleep little. From as young as five years of age, children ran after the herd on snowshoes with stones attached to them.

The Chukchi went running (sometimes in heavy body armor) and participated in wrestling every day. Also, mock one-to-one fights with spears - their main weapon in close combat - and a rugby-like sport played with a ball made of reindeer hair were very popular.

“The Chukchi, especially the reindeer herders, are remarkable walkers,” wrote Staff Captain N. Kallinikov at the beginning of the 20th century. “They really seem to be men of steel when it comes to overcoming fatigue, hunger or lack of sleep… particularly in their younger years.”

Chukchi warriors.

Public DomainThe Chukchi had no fear of death. They were far more afraid of displaying cowardice and leaving behind a negative memory of themselves. Once captured, warriors often starved themselves until they died.

In battle, the Chukchi not only skillfully wielded a bow, spear or knife, but, if needed, could successfully fight with a reindeer herder’s lasso, spear throwers they normally used for launching darts at waterfowl when out hunting and even the sticks with which they halted reindeer that had separated from the herd.

The Chukchi didn’t use shields, but their highly-developed dexterity helped them to dodge the arrows of their eternal enemies, the Koryaks (a related indigenous people living south of the Chukchi who had accepted allegiance to Russia). Nevertheless, the bodies of the warriors were protected from head to knee by lamellar (platelet) armor made from walrus skin, walrus tusk, reindeer ribs, whalebone and/or iron.

Russian explorers of Siberia at the end of the 18th century observed that 20 “savage, fierce, unbridled and ruthless” reindeer herder Chukchi were easily able to rout 50 Koryaks. The nonmigratory Chukchi, who lived by the coast, were less bellicose than their nomadic brethren, but they were also regarded as first-rate fighters and a strong adversary.

At first, the Russians’ firearms seriously frightened the Chukchi, who regarded shots as “divine thunderbolts” and wounds from projectiles as “lightning injuries”, but they got used to them fairly quickly. Since the Russians were in no hurry to sell muskets to the dangerous reindeer herders, the latter used to acquire them as trophies or barter them from the Koryaks.

The Chukchi preferred to fight in winter. Clandestinely crossing many kilometers on reindeer and dog sleds, they would mount surprise raids on enemy settlements, killing people, burning houses, taking prisoners and destroying everything they could not carry away with them. They deliberately doomed the enemy to starvation by trashing food stocks.

While several dozen men would usually go on expeditions against the Koryaks, against such a formidable enemy as the Russians the Chukchi tribes would often deploy several hundred warriors and, in exceptional circumstances, up to 2,000. For instance, in the 1731-1732 military campaign, the Pavlutsky detachment killed around 1,000 Chukchi in battles.

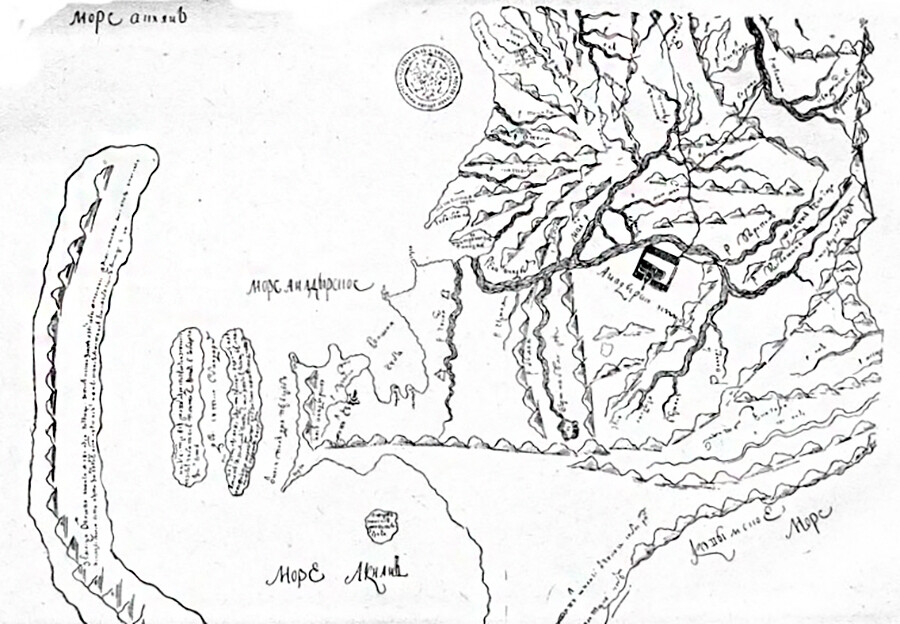

The Anadyrsk ostrog.

Public DomainThe Chukchi’s chief mode of warfare against the technically superior Russians was to mount ambushes. In addition, they ably exploited any enemy mistakes to their own advantage. For instance, the Cossacks once set up camp on Mount Mayorskaya, which was surrounded by frozen water and, counting on the ice being thin, failed to post any sentries. The Chukchi were not put off by the danger of ending up in the water. After crawling along the ice on their stomachs, they slaughtered the intruders unimpeded.

The war against the Chukchi that started in the mid-17th century was a long and bloody affair for Russia. Despite the fact that the Chukchi were losing hundreds of their fierce warriors in clashes, they stubbornly refused to recognize tsarist rule.

The Russian troops also suffered heavy defeats, at times. For instance, 30 Cossacks led by Colonel Afanasy Shestakov were killed in a battle beside the River Egacha in 1730. Seventeen years later, a battle on the River Orlovaya ended with the death of Major Pavlutsky and 50 of his men. Given the limited resources that Russia had at its disposal in the region, these setbacks hit painfully home.

Chukchi, 1906.

Paul Niedieck/Public DomainIn the end, St. Petersburg simply decided to reach an agreement with the unsubmissive reindeer breeders. An important step towards normalizing relations was the closure in 1771 of the Anadyrsk ostrog (fortified settlement), which had been a major source of aggravation for the Chukchi (the maintenance of the fortress had cost the public coffers very dear in the century of its existence). After this, emissaries of Empress Catherine II were able to conduct successful talks with the local leaders, who were known as toyony.

In 1779, Chukotka was officially incorporated into the Empire. The Chukchi were exempted from payment of tribute for 10 years and effectively retained full independence in their internal affairs. Even in the early 20th century, many of them had no idea they were Russian subjects.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox