Russia’s bloody struggle against the terrifying Chukchi aboriginals

The view that the conquest of Siberia - and later the Far East - began in earnest in 1581 with the journey of Timofey Ermak and his Cossacks against the Siberian khanate, is a commonly held one in Russia. Ermak was hired by brothers Yakov and Grigory Stroganov, who received lands in the Prikamye and salt mines in Sol-Vychegodsk. From there, the colonists moved eastward, but were met with resistance in the face of the last vestiges of the Golden Horde. Kuchum Khan presented a real threat to Ivan IV (often remembered by history as ‘Ivan the Terrible’). The story goes that Ivan allowed the Stroganovs to hire Cossack muscle to solve that problem.

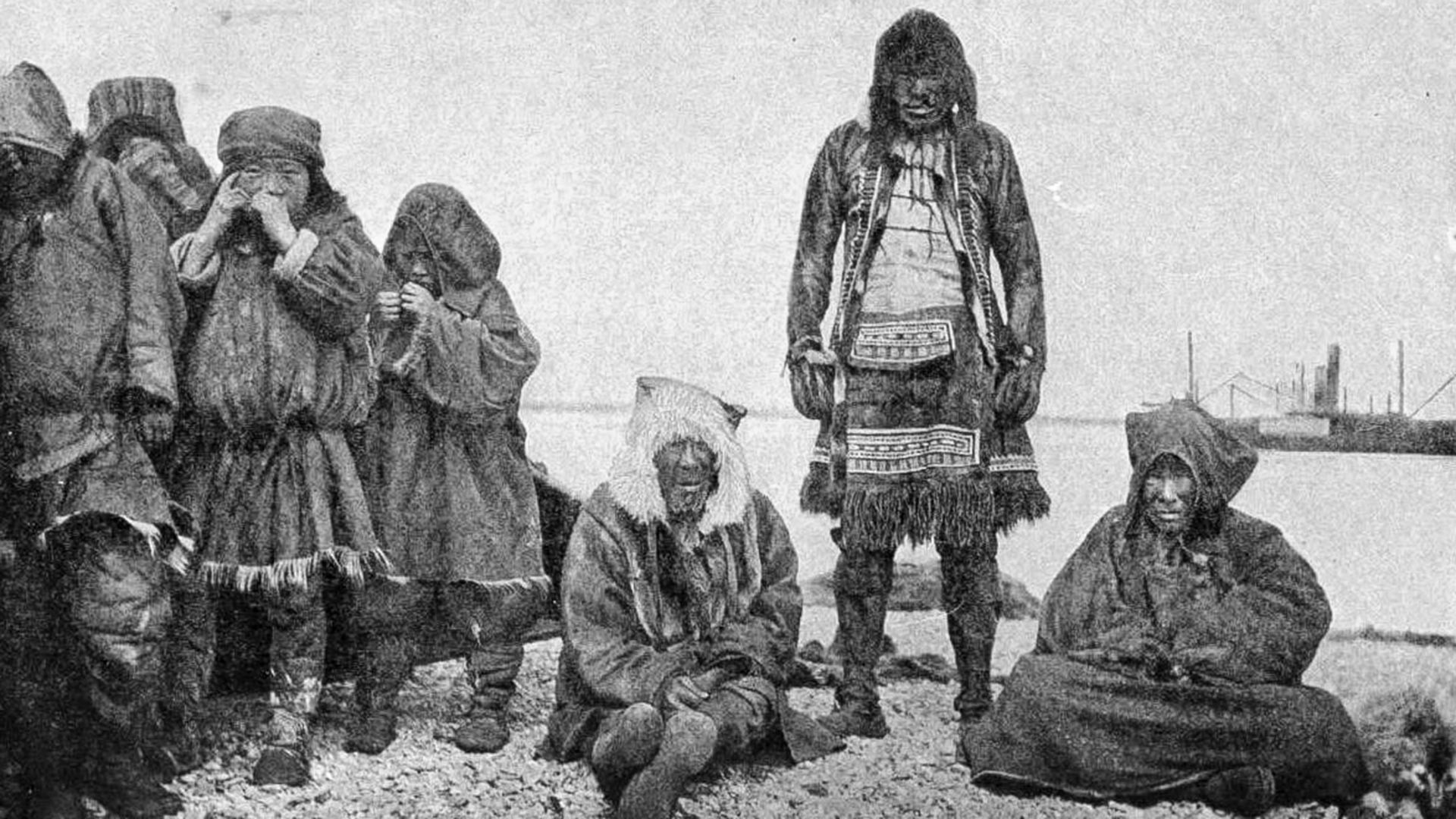

A Chukchi family in front of their home

Public domainAfter the defeat of the Siberian khanate, Russian landlords were fresh out of rivals, and they moved to conquer new lands. The Cossacks had become the colonialist tsardom’s go-to mercenaries. Some were going to fight of their own volition, while others were hired. A third group were the offspring of the ones who migrated. They traveled by rivers, collecting ‘yasak’ (“tribute”) from the natives they encountered. Staying in one place never made sense - the aim was always southern Siberia and its arable lands. Tsar Ivan wouldn’t have had it any other way, requesting new subjects to pay yasak, and with an eye to acquiring new goods for expanding trade. And Russia’s north was always rich with fur, fish, seal lard and walrus tusk.

READ MORE: What life is like for Russia’s indigenous folk - 100 years ago and today (PHOTOS)

Little by little, the colonists traversed northwards on what is now modern Russia, toward Siberia, founding ‘ostrogs’ (“towns/wooden forts”) and collecting tribute. Bloody struggles often erupted, but often ended quickly after a show of force by the Cossacks.

There’s a first time for everything, however, and the conquerors learned the hard way that flexing their muscle wasn’t always going to do the job. The Cossack’s sickle met with a rock in the face of the Chukchi.

The Chukchi

The Chukchi are a fascinating people. They consider themselves “true humans” - or “laurovetlan”. The neighboring peoples were second-class beings to them. The same attitude was displayed toward the Russian colonists.

Invaders

Yury TulinThere are no verifiable accounts of when exactly first contact took place. One of the versions posits that it happened in 1642, near the Alazea River.

But there is reason to believe that it was, in fact, earlier. In any case, the Cossacks were aware of the existence of a “fearsome people” in the area. The Even, Evenki, Yukagir and Koryak people related to them the story of their age-old struggle against the Chukchi. However, Cossack chieftains Ivan Erastov and Dmitry Zyryan did not take these tales too seriously. And when the Cossacks finally collided with the Chukchi, they simply declared that their land was now subject to the rule of Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich, and must pay yasak. The aboriginals, however, had different ideas. An armed conflict ensued with the participation of the great future explorer - then still a Cossack, Semyon Dezhnev.

Russian explorer Semyon Dezhnev

SputnikChieftain Erastov subsequently wrote to tsar Mikhail with the story of the battle that “lasted an entire day and night”. He attributed this to the Chukchi’s complete lack of fear of firearms: the Cossacks simply did not expect to face such bravery and fearlessness. If the Evens and the Yukagirs quickly scattered even before the thunderous roar of their guns, the Chukchi were incredibly steadfast, and took the challenge head-on, returning fire with their bows and arrows. Their stubbornness took the Cossacks by complete surprise.

This underestimation of the enemy owed itself entirely to a lack of basic knowledge of the Chukchi mentality. The tribe’s entire life had been a struggle for survival. Moreover, they did not fear death - a fact the Cossacks would be made aware of later.

However, the Russians were not about to withdraw. The process of colonizing the Far East was well underway, and they were knee-deep and unwilling to budge from the aboriginals’ lands.

One curious reason for that were walrus tusks. It was an incredibly precious resource, one that the Russians considered the height of stupidity to give up on.

Diplomacy VS war

Chukchi warriors

Public domainThe Cossacks did initially plan on settling matters peacefully. However, it was a complete failure. While the Cossacks weren’t skilled diplomats by any stretch of the imagination, the hardships they faced were owed almost exclusively due to the Chukchi’s unwillingness to accept even the slightest compromise.

The “true humans’” primitive system of governance was a real stumbling block. They didn’t have a central government. Each clan was governed by a ‘tayon’, but even he could not decide the fate of his tribesmen - acting only as counsel, providing an advisable course of action. However, if that wisdom went in stark opposition to the opinion of the majority, he was simply killed, and his status was handed down to a more agreeable member of the tribe. There was nothing the Cossacks could say to change that. War was the only way.

Despite the primitive lifestyle and weapons, a Chukcha warrior was a formidable adversary. His armor, forged from the skins of seals and walruses, covered his body from the neck down. Some warriors had armor made of deer bone and antlers. The shields, meanwhile, were made with seal and walrus skins.

Chukchi boats

Public domainThe Chukchi weapons of choice were the bow, spear, knives and slingshots, which they mastered from early childhood (although, according to the Russians, they weren’t “too skilled” in using the latter). And whenever the threat of capture arose, a Chukcha would take his own life.

One of the notable differences the Chukchi exhibited compared to their neighbors were their military tactics, honed in a life of constant raiding.

The “true humans” were expert masters of disguise and would often outsmart their enemies by luring them into a trap. Each clan had its own famous warriors. One of their traditions consisted of tattooing a small dot on the palm of their hand after a kill. The more dots - the more respect a warrior garnered.

The ‘conquistadors’ of Chukotka

At the time of the Chukotka Peninsula’s conquest, some 10,000 individuals belonging to various clans had lived there, with frequent inter-tribal conflicts breaking out over deer and territory. The Russian colonists were greatly outnumbered, with only a couple of hundred warriors. However, they were joined by the Yukagirs, the Koryaks, the Evens and other peoples who had a bone to pick with the Chukchi. Unfortunately, they weren’t very useful against the “true humans”, whom they feared. A number of them would scatter before a battle would even begin.

The main stronghold of the colonists was the Anadyr ostrog, erected in 1652 with Semyon Dezhnev’s participation. For over 70 years, the stronghold was the only place they felt safe from constant Chukchi attacks.

Finally, St. Petersburg had had enough.

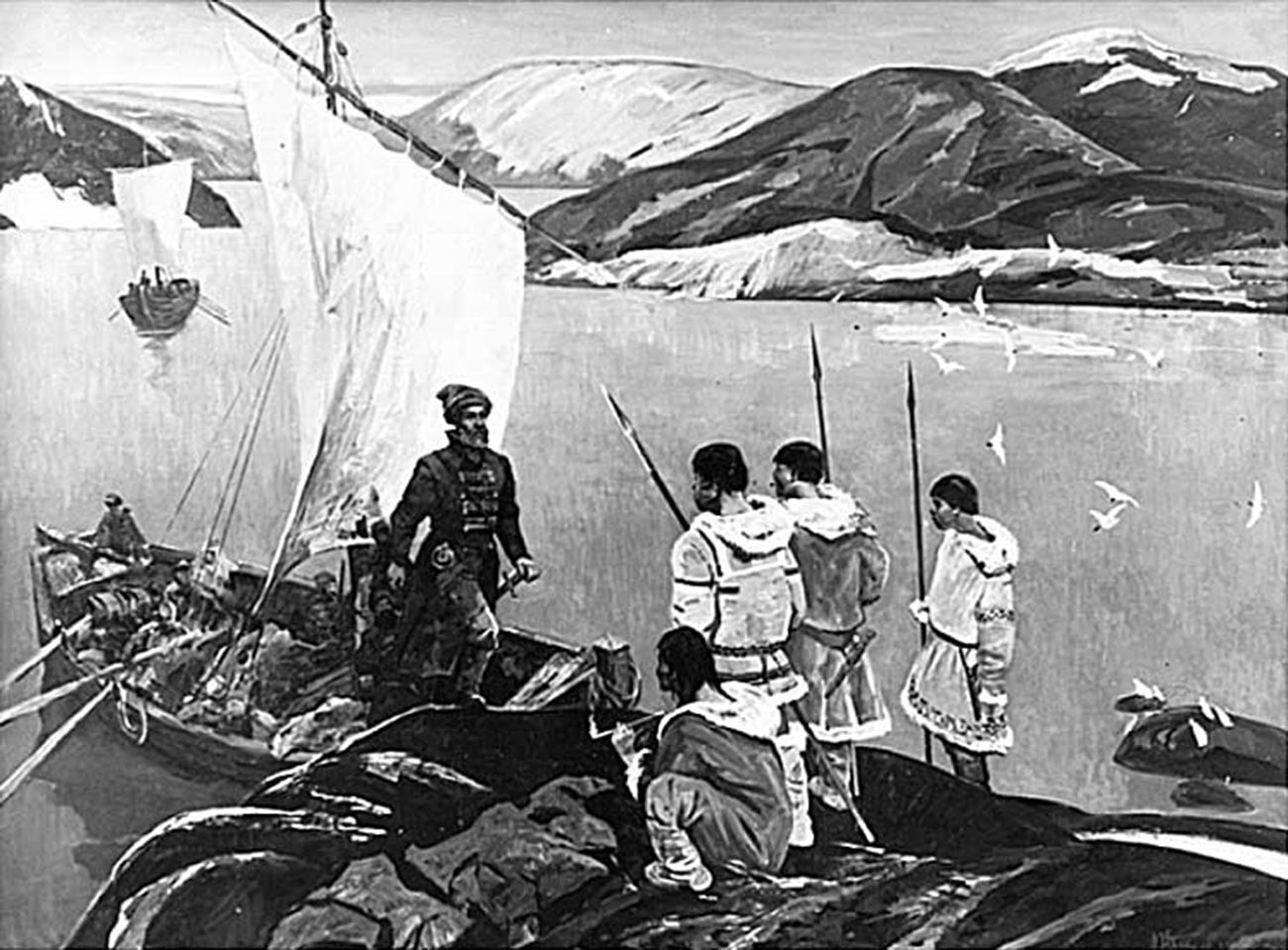

Semyon Dezhnev's expedition, 1645 or 1648

Klavdy LebedevA large-scale military operation was mounted by chieftain Afanasy Shestakov. The objective was to take Chukotka, Kamchatka and the Okhotsk Sea coastline. Captain Dmitry Pavlutskiy was sent to help. The commanders were to unite their forces and crush the Chukchi in a decisive offensive. However - both being strong-willed leaders, they failed to agree. And in 1729, both armies chose their own separate routes of attack.

Shestakov’s assault failed about a year in, ending with his death in an ambush. Pavlutskiy would only learn of this months later. By then, the captain and the Koryaks he’d had with him managed to defeat several Chukchi armies and locate their camps. Following Petersburg’s orders, Dmitry Ivanovich went scorched-earth on the aboriginal peoples, leaving nothing but ash in his wake. Pavlutskiy actually managed to impress the Chukchi so much that his nickname - Yakunin, became synonymous with the archetype of the “great enemy”.

The bloody war between the Russians and the Chukchi actually found its way into a lot of Chukotka folklore, recorded for posterity by ethnographer Vladimir Bogoraz. Yakunin figures prominently there, and always dies at the end. There are two versions dealing with his legend: the first is a sort of composite of the way the Chukchi viewed the Cossacks. The second references Pavlutsky’s actions directly.

Pavlutskiy, however, never managed to accomplish his task. He was promoted to Major and transferred to Yakutsk. And, for a time, the clashes between the colonists and the Chukchi subsided. Some clans had even begun paying yasak.

But the tentative peace was short-lived.

The photo shows a Chukchi, or Chukchee, family: a man, old man, old woman, and children lined up for a photo neatr the shore, with a ship in the background. Anadyr (Novo-Mariinsk), Russia, summer 1906.

Public domainIn the early 1740s, Chukchi had become emboldened enough to once again carry out raids on neighboring tribes and colonist hunters. That’s when Dmitry Ivanovich came back with a vengeance, and, once again, the fighting began anew.

But, the Chukchi were prepared this time, and staged an elaborate show for his benefit. They withdrew their deer from the Anadyr ostrog, waited until Pavlutsky came out with a war party, and baited him into a trap. The commander - by then an expert in the enemy’s tactics and trickery - ended up falling prey to his own lack of patience, and was killed because of it.

A different strategy

Attempts to conquer Chukotka continued until 1763, with no success. The treasury was incurring huge losses - more than 1,300,000 rubles was spent on sustaining the Anadyr party’s campaign. Meanwhile, yasak revenues didn’t even reach 30,000. The decision to end the campaign was, therefore, a sensible one. The Anadyr ostrog was liquidated and its inhabitants relocated.

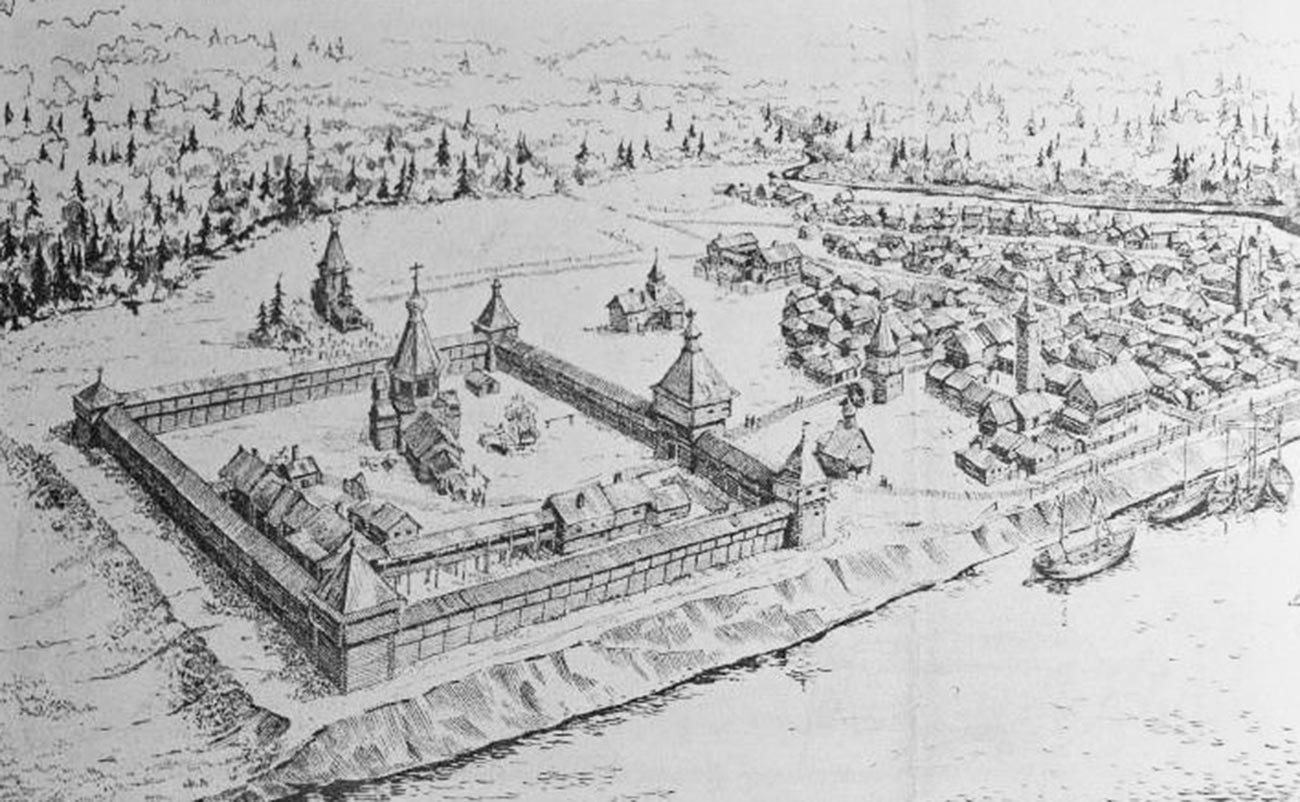

Anadyr Ostrog

M. I. BelovIt would seem that the history of the Chukotka conquest should have ended there. But it didn’t. As soon as the Russian Imperial fleet was gone, the territory had caught the attention of the French and English. The Russians could not allow them to establish a foothold on the peninsula. And so, Catherine II (Catherine the Great) ordered the colonists to return - but not as conquerors. Instead, they came extending an olive branch.

And the strategy worked. Trade began to flourish between the Cossacks and the Chukchi. with annual trade fairs, where goods were exchanged, were set up and the two peoples were finally speaking the same language. The natives, however, never paid yasak, and their status as subjects was little more than a formality. The formal annexation of the Chukotka Peninsula did not happen until much later, during the time of the Soviet Union.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox