“Today, the work continued at the Gur-e-Amir mausoleum. Anthropologists and chemistry specialists scrupulously studied Timur’s remains. The scientists found out that there was remaining hair on the skull. The possibility of restoring a fairly precise portrait of the conqueror was determined,” ‘Izvestiya’ newspaper wrote on June 21, 1941. And, early morning the next day, Nazi Germany attacked the USSR. A myth took root among the masses that these two events were linked by “Timur’s curse”.

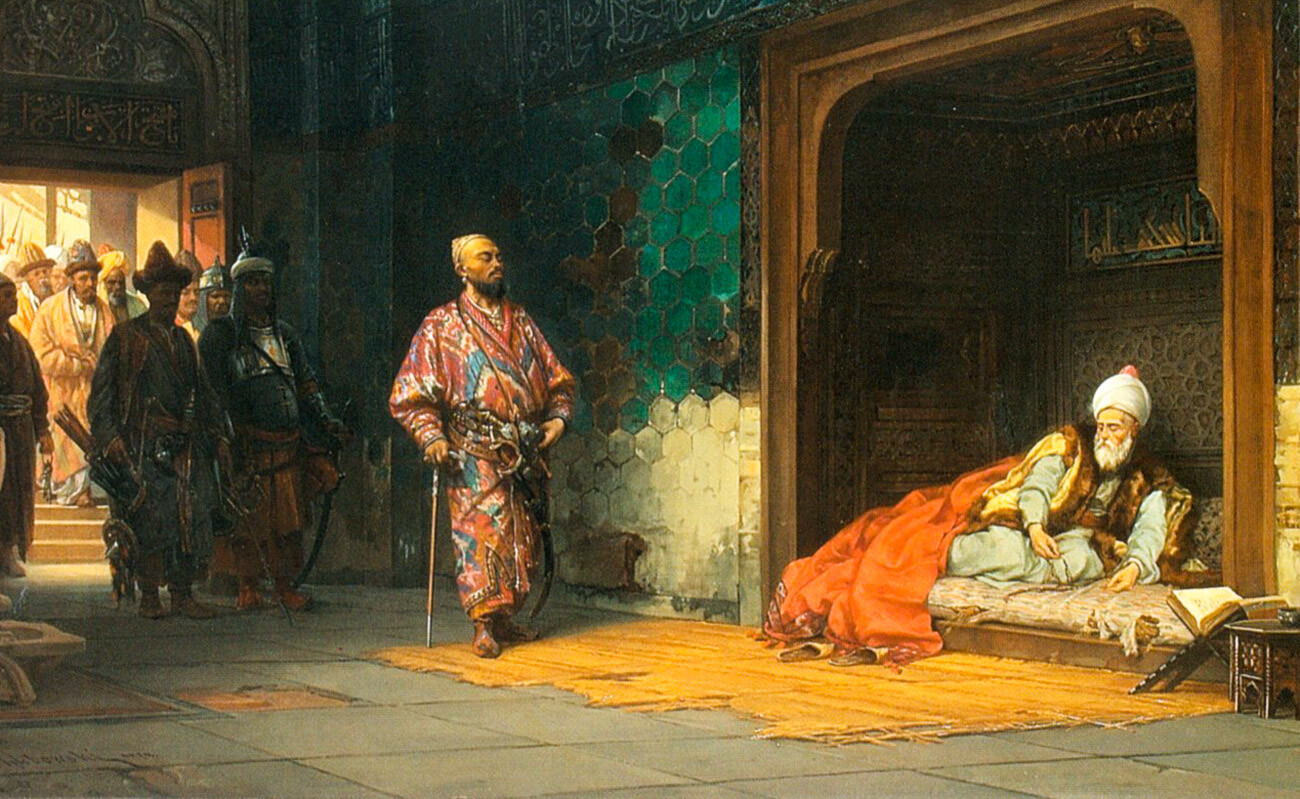

"The Capture of Bayezid by Timur", 1878

Stanislav KhlebovskyTimur, or Tamerlane (1336-1405), was a Central Asian ruler and founder of the Timurid dynasty. He started as a warrior who gathered his own party; then he became a significant commander and took an important government position in the Turkic-Mongol state of Moghulistan. Later, he was elected the first ruler of a new Timurid state with its capital in Samarkand (modern Uzbekistan), existing until 1507. Conquering a lot of land, Tamerlan began ruling over a major part of Central Asia, as well as territories in Mesopotamia and the Caucasus, modern Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Syria.

Timur was not a descendant of Genghis Khan, the founder of the Mongol Empire, so, according to Mongol tradition, he had no right to bear the title of khan – he was, instead, referred to as the “Great Emir”. But, marrying the daughter of one of Genghis Khan’s descendants, he could now take the honorary title of “khan’s son-in-law”, which gave him more freedom of action and power.

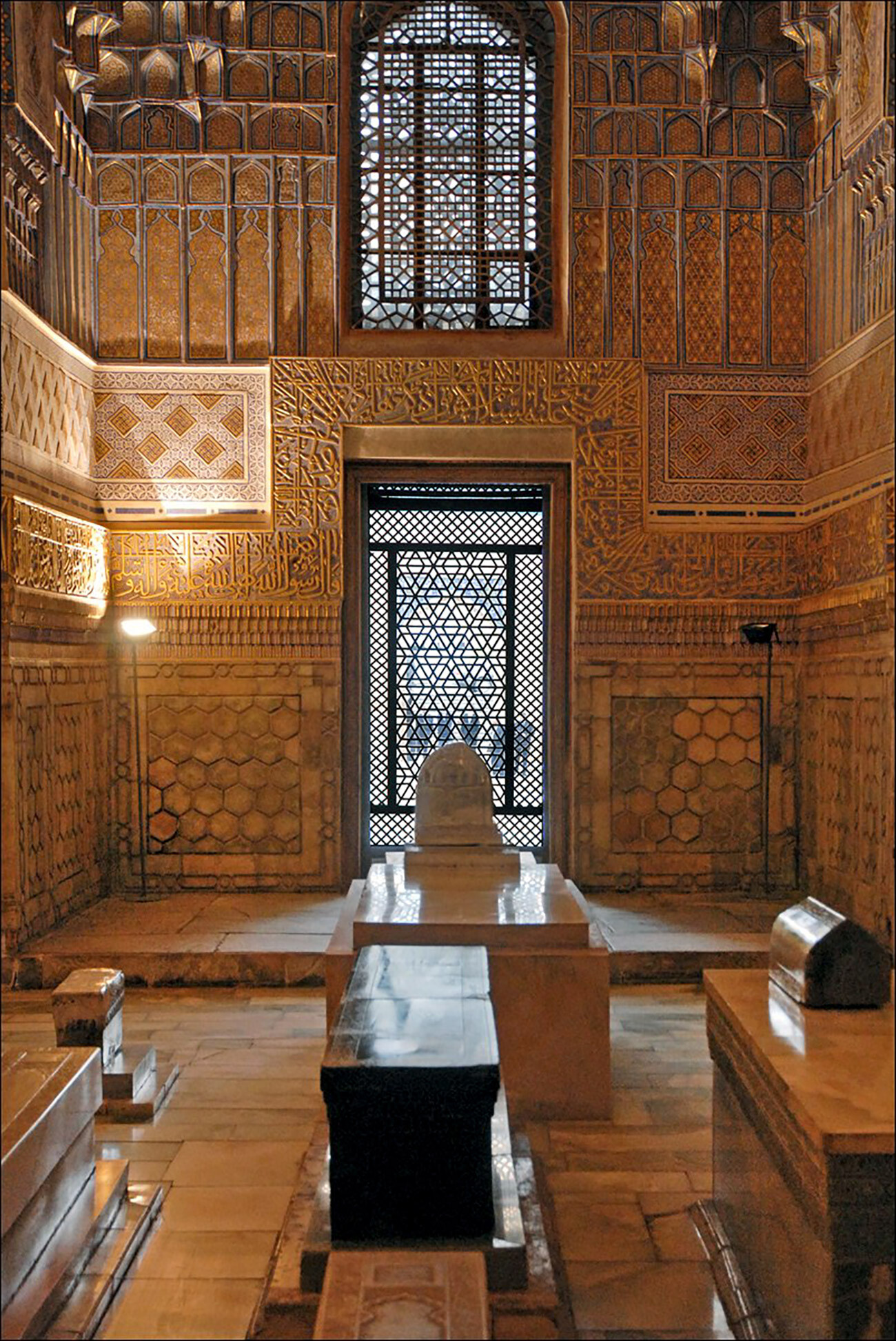

Gur-e-Amir mausoleum of Timur in Samarkand

w0zny (CC BY-SA 3.0)Apart from conquest, the great emir did a lot for the development of culture in his country and many masterpieces of architecture in Samarkand were built under his rule. At his order, the construction of the Gur-e-Amir mausoleum began in the city, where, later, he was buried, along with some of his descendants.

Gur-e-Amir is considered one of the most important monuments of Islamic architecture, which influenced many religious buildings. It was this mausoleum that inspired the architect of the Taj Mahal mausoleum and mosque in India (which, by the way, was commissioned by a descendant of Timur in the middle of the 16 century).

Below in the center is the tomb of Timur

Jean-Pierre Dalbéra (CC BY 2.0)Archaeologists decided to open up Timur and his descendants’ tomb and to study their remains in 1941. The directive on the excavations in Soviet Uzbekistan was allegedly personally signed by Joseph Stalin.

It’s unclear why they got the idea to study the graves. There are versions that the digging was initiated to save the remains – at the time, the construction of a hotel began next to the mausoleum and, in the course of construction work, water began to seep into the tomb.

Officially, the opening of the tomb was timed for the 500-year anniversary of Uzbek poet Alisher Navoi, who lived in the Timurid Empire and was close with the grandchildren and the descendants of Timur. The scientists hoped to uncover new historical details or find artifacts that could be shown to the public.

Soviet scientists opening the tomb of Timur

Uzarchive AgencyIn June, a large team of Soviet scientists began opening up the tomb. Cameraman Malik Kayumov, sent to film the important process, later said in an interview that, during a break, he met several elders who told him about the curse – the tomb should not be opened or a war will break out! Kayumov even took them to the expedition leaders and they showed a 17th century book that said in the Arabian language: “Who disturbs Tamerlan’s tomb will release a spirit of war. And such a bloody and terrible slaughter will commence that the world has not seen in all eternity.” There were even legends that fearful prophecies were written directly inside the coffin: “Whomsoever opens my tomb shall unleash an invader more terrible than I.”

Undeterred by superstitions, the scientists continued their work. On the next day, June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the USSR.

The legend about Timur’s curse allegedly reached Stalin himself, who ordered to put the remains back in their place. There were rumors that he was ready for any mystical rituals to change the course of the war.

On November 19-20, 1942, the ceremonial re-burial took place according to all Muslim honors. Surprisingly, on this day the most important battles under Stalingrad happened – the Soviet troops launched a counter-attack that led to the beginning of the key turn in the course of the war.

The opening of the tomb had important historical significance. After studying the skeleton and the skull of Timur, the head of the expedition, sculptor-anthropologist Mikhail Gerasimov managed to make an incredibly detailed description of what the Medieval ruler looked like and even rebuild his portrait.

Image of Timur reconstructed by Mikhail Gerasimov in 1941

shakko (CC BY-SA 3.0)He learned that Timur had typical Mongoloid facial features, he had ginger-red hair, a mustache hanging down the sides of his lips and a wedge-shaped beard. Aside from that, he was quite tall (especially for a Mongol) – about 170 centimeters.

Archaeologists also documented the fact that Timur had an injured leg (in Russia, he had the nickname ‘Timur the Lame’). Despite the fact that the great emir lived for 68 years – to a very old age in those times – his remains spoke of great physical strength and vitality, which he possessed until his very death.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox