'Village women,' 1894, by Sergei Vinogradov

“I have begun to bleed.” A village girl runs to her mother and the mother responds by slapping her in the face! The child, of course, bursts into tears. But, this cruelty was due to folk traditions.

'Village girls,' by Sergei Vinogradov, 1938. Both girls are wearing red colors in their clothes, which means their periods had already started. The girl on the right is wearing an apron over her chemise, which is also a sign of a young woman.

Public domainRussian peasants in the 19th century rightly associated the beginning of menstruations with the emergence of the fertile power in a girl. The slap in the face was given to the girl, in order to make her blush so she would “always have colors” (menstruation, that was also called ‘the thing on the shirt’ or simply ‘the bleeds’).

As historian Natalia Mazalova writes, in Smolensk province, in order to preserve the childbearing capacity of girls after their first menstruation, they put on their mother’s shirt in which she met her first discharge of blood.

Among the southern Slavs in Serbia, the ritual was harsher – “for the girl to be happy, after the first period, her mother lightly smears her forehead and eyebrows with menstrual blood.”

Why do we know so little about menstruation among Russian peasant women? A peasant family always needed workers. Girls who entered their periods soon married off to form a new family, which would produce new workers. Children died young, which provoked women to give birth more often and, after several births, combined with hard work and low nutrition, menstruation could just cease earlier in life. That’s why most women did not have periods for any lasting time.

What did women use during their periods in place of contemporary hygienic tampons? There is not much information on this issue, but it is known that in the 18th-19th centuries, educated and wealthy women could have used menstrual belts. Peasant women used rags or simply clamped the bottom of a long shirt between their legs.

'A home in Vologda region,' 1925, by Nikolai Terpsikhorov. This grown-up woman is alone at home during a summer day, which is unusual for working months. That means she is probably on her periods, as women were forbidden to work in the fields during these days. However, cleaning was not forbidden.

cultinfo.ruThe onset of menstruation officially turned a girl into a woman and gave her new rights. For example, the right to wear maiden clothes – an underskirt and poneva (a woolen skirt usually sewn from several pieces), as well as towels and aprons over her basic shirt.

The appearance of menstruation meant that a girl could now greet the village adults like an adult, by bowing to them, go to parties with young people and look for her future husband.

The Orthodox Church, following the Old Testament (Leviticus 15:19-33), however, declared menstruating women to be impure, forbidding them to attend church, kiss the cross and icons.

What if menstruation suddenly fell on the wedding day? Then, the wedding was postponed or the newlyweds were married, with the bride only being allowed to kiss the cross symbolically, without actually touching it with her lips. And in Pskov Region, writes Natalia Mazalova, “the priest would ask the bride allegorically, ‘pine or spruce?’ The answer of ‘spruce’ meant that the girl was menstruating and the priest read a purifying prayer before the ceremony began.”

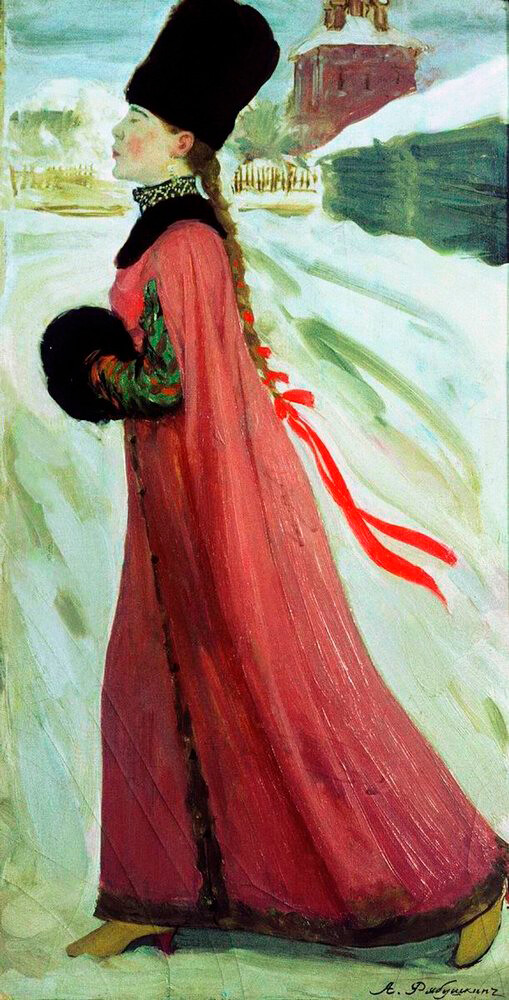

'Moscow girl of the 17th century,' by Andey Ryabushkin, 1903. This girl is single, which we can tell by her single braid, and is mature as a woman, which her red clothes indicate.

Public domainFolk beliefs also said that a woman during menstruation possessed dark energy. Women during their periods were forbidden to plant anything, to take part in field works, to touch flour, dough, grain – otherwise they would be considered to be spoiled. It was forbidden to be present at baptisms and births, funerals, weddings or to be the godmother of an infant. A menstruating woman was also considered especially vulnerable; for example, she should not go to the woods to pick mushrooms and berries by herself, because a bear might kill her, having “smelled blood” (which was, of course, only a popular belief).

Women were not recommended to cook during this period either, but were not forbidden to do household chores, such as laundry and cleaning, although they were advised to be careful and not apply much physical effort.

The Laundering Girl, 1889, Khariton Platonov

Public domainBut in Russian villages, menstruation wasn’t only considered “bad”. Menstruation allowed women to perform magical rituals – deeply pagan in essence. Historians Shumov and Chernykh write: “The perception of periods as the center of female nature… sometimes proved stronger than prohibitions, overcoming the cultural, social and economic isolation of a woman… made her condition desirable and reminded about her exclusiveness.”

READ MORE: How women ran business empires in Tsarist Russia

The Slavs of Polesye thought that it was better to plant potatoes for a menstruating woman – as it would yield better. In Serbia, “a woman who wanted to have a son next, during the first period after childbirth, had to dye corn grains with her blood and feed them from an apron to a rooster; if she wanted to have a daughter in the future, then she must feed a hen”.

The menstrual blood itself was considered a “highly potent magical poison”. Putting some drops in food or drink, it was supposedly possible to bewitch a man and ‘anointing’ a person, especially a child, with such blood could bring them to their grave.

Many magical tricks were aimed at relieving the menstrual pains – but they were connected not with the “blood” itself, as an unclean substance, but with water left after washing soiled linen. The most popular trick was to “divide” this water (which symbolized menstruation) into several parts and get rid of all of them except one, which was left “for oneself”.

'Milkwoman,' 1826, Alexei Venetsianov

Russian museum/Public domainIn Nizhny Novgorod Region, in order to relieve the pain, a woman poured water from a trough three times to the right and to the left while washing laundry, accompanying her actions with the words: “Strange water to the left, my water to the right.”

In Siberia, in case of too much pain, a folk healer would take a pot of water after washing soiled underwear and pour it on different sides at the crossroads. There was also a simpler magic – the water had to be poured out on a birch tree or on the lower parts of a peasant hut.

Another known way to suppress menstruations was to use wood chips from mill dams or shutters from windmills – i.e. symbolic barriers and seals. Women burned them and then drank the ash dissolved in the water.

However, it was important that laundry with traces of menstruation could not be buried or burned and water after washing could not be poured on the ground – it was allegedly a way to make yourself infertile. Water was only poured back into the water (the laundry was mostly done on rivers and ponds) and the clothes a woman had her first period in were kept in the family – to pass them on to the daughters.

To avoid having children, there was an incantation known in Smolensk Region: A woman would throw her shirt with traces of her period blood on a hot stove or stones in the bathhouse and pour water on it saying: “As this blood bakes on the stove, so may my future children bake in my womb” – according to the folk beliefs, all of a woman’s future children were concentrated in her menstrual bleedings.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox