The fascinating, boring lives of Russian tsarinas

Since the times of Ivan the Terrible, a bride for the tsar would be chosen at a bride-show, a tradition brought to Russia from Byzantium. The most beautiful daughters of noble families were brought to Moscow from around the country, and the tsar’s matchmakers would choose several of them. Not nobility or wealth mattered, but only the beauty and the health of the bride. 6 or 7 women were eventually invited into the tsar’s chambers for the young groom to make the choice himself. After being chosen by the tsar, the girl would be installed as a tsarina.

Live and die like a tsarina

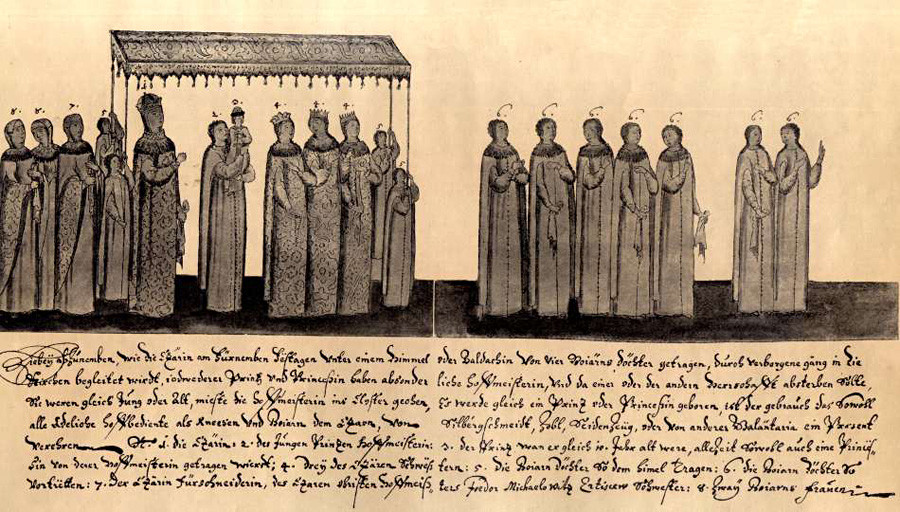

'A tsar's bride being installed as a tsarina,' an engraving by Vyacheslav Schwarz.

Vyacheslav Schwarz/Tretyakov GalleryThe first wife of Ivan the Terrible (1530–1584), Anastasia (1530–1560) was believed to have fallen victim to black magic, ordered by the boyars. Ivan had several of them tortured and executed. The tsar was devastated after his wife’s death, but his second and third wife also died early, with the third, Marfa Sobakina, dying two weeks after the wedding in 1571 (this also resulted in executions of many people, including Marfa’s relatives). Poisoning was most likely the actual cause, as Russians often used different health-aiding potions and brews for medicine.

''The bride-show of the tsar Alexey Mikhailovich (Alexis of Russia),' 1886, Konstantin Makovsky

Konstantin MakovskyMaria Khlopova (died 1633), the first bride of Mikhail Fyodorovich, the first Russian tsar of the House of Romanov (1596 – 1645), fell ill shortly after her engagement to the tsar and vomited for several days. This was enough for the boyars to declare her unfit for the marriage and send her into exile. Then, Mikhail’s second bride, Maria Dolgorukaya (1608–1625), died 5 months after being declared a tsarina. So when Mikhail chose his third bride, Evdokiya Streshneva (1608–1645), he brought her to the palace only three days before the arranged wedding – the tsar feared that Evdokiya could be poisoned, too.

Many people would want a young tsarina dead – first, the families of the ones that weren’t chosen at the bride-show. So in the 17th century, strict measures were applied at the palace to protect women of the tsar’s family.

Ash in the footprints

Tsarina's winter carriage and suite, a 17th-century engraving.

Augustin MeyerbergWhen a noblewoman became a tsarina, she was no longer allowed to visit her relatives at their home anymore. Technically, it was forbidden for her to see common people. So her parents and other close relatives would be moved to live in the palace and given high positions at the court.

The tsar’s wooden palace at the Kremlin was huge, with hundreds of rooms, and a good half of women’s chambers. The tsarina and her daughters would not take part in official ceremonies where men were present. But they had their own ceremonial hall – the Golden tsarina’s chamber. Here, on her throne, the tsarina would receive visitors during important Orthodox feasts and the name day of her patron saint. These were the only days she could see people previously unknown to her – mainly clergy, noble boyars, and their wives. When the tsarina and her daughters would travel to monasteries outside Moscow, they would go in a closed carriage. When they walked from the carriage to churches, servants would hold velvet curtains around them that protected the women from unwanted exposure.

'Tsarina visiting a women's convent,' 1912, by Vasiliy Surikov.

Vasiliy Surikov/Tretyakov GalleryIn the women’s chambers, all staff and servants were female. The highest female officials were called boyarinyas (boyar’s wives). They oversaw the tsarina’s treasury and supervised the tsarina’s clothing and food. One of the boyar’s wives also served as a judge for all conflicts and crimes inside the women’s chambers.

However, if serious crimes, like a jinx or black magic, were suspected, the case would be transferred to the horrendous Privy Prikaz, an institution for political investigations, which the tsar personally oversaw.

Tsarina and her suite during a ceremony, a 17th-century engraving.

Augustin MeyerbergIn 1638, work women of the tsarina’s laundry chamber reported that one of their girls, Daria Lamanova, had stolen fabric for the tsarina’s underwear. An investigation revealed that Daria had been meeting a sorceress named Nastasya and had sprinkled the footprint tsarina Evdokiya left in the courtyard’s dirt with ash – a supposed attempt to curse the tsarina! All women involved in the case were interrogated in Privy Prikaz and eventually died of torture.

The fairer tsardom

The outfits of Russian tsarinas

Fyodor SolntsevAside from boyarinyas, the tsarina would have around 50 female servants that formed her daily suite but didn’t live inside the palace, and younger noblewomen who were brought up with the tsar’s daughters as friends and close aides. Besides, there would be an army of servant girls. They made the tsarina’s bed, sat in the rooms to perform petty tasks, mended and washed clothes. There were special women who would read aloud to the tsarina and her daughters, sing religious hymns, and for coarse entertainment, the tsarina often kept dwarf women and jester women.

There were male servants there, too. First, they were priests who conducted religious services inside the tsarina’s rooms (just as the tsar, she had a house church and a separate room for praying next to her bedroom).

The Golden Chamber of the tsarina in the Moscow Kremlin

Mikhail Kuleshov/SputnikSeveral dozen young boys (10-15 y.o.) would help the tsarina and her daughters at the table; as soon as they reached maturity, they were sent away from women’s chambers. About 100 grown-up men guarded the chambers day and night but were never allowed to see the women, just like the stokers, who would maintain the women’s chambers furnaces only when no women were present.

Apart from visiting churches and monasteries, the tsarina would have some charity and official work to do. Often, noble people and women sent their complaints to the tsarina rather than the tsar – a tsarina had fewer state duties and could attend to some cases by addressing the tsar directly.

The bedroom in the Terem Palace of the Moscow Kremlin

Legion MediaThe tsarina also dedicated a lot of time to making high-end clothes, often doing the embroidery herself. A cloak made by a tsarina was one of the most stately gifts a foreign ambassador or ruler could receive from the Russian royal family. A tsarina’s evenings were spent with the tsar and family. They could play chess, read the Bible or Orthodox books, listen to stories told by travelers or pilgrims who were often invited to entertain the tsar and his family. The tsar could spend the night in the tsarina’s rooms, but it was not an everyday occurrence and required special security measures.

The women’s chambers came to an end with the rule of Peter the Great (1672–1725). His mother, Natalya Naryshkina (1651–1694), was the first Russian tsarina who ever visited a theater performance, loved to dance and watch diplomatic receptions. She literally tore down the old habits and rules of the women’s chambers, and eventually, the division of the palace in two halves was banned by her son – by the 18th century, the Russian royal court was much like European ones.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox