Royal diseases: 4 Russian rulers and heirs leveled by sickness

"The Tsar (Peter the Great) on his deathbed," a painting by Johann Gottfried Tannauer. It was a kidney disease that killed Peter I

Public DomainWhen Emperor Pavel I died in his castle in 1801, the official cause given was a stroke, although many Russians suspected — correctly, it turned out — that the tsar had been killed by a group of aristocrats. The official story seemed plausible: Despite Russia’s turbulent history, chronic illness has felled more leaders than has violent overthrow.

Peter the Great: neurological problems, asthma, kidney disease

Yet another painting of Peter I on his deathbed, by Ivan Nikitin.

Public domainPeter, according to contemporaries, had “beautiful features and noble posture,” and was very tall (203 centimeters, or 6 feet 8 inches). The tsar, however, didn’t enjoy good health. He was thin for his towering frame and suffered from several illnesses during his 52 years.

From time to time, Peter would seemingly become enraged for no reason. At a parade once, a Danish ambassador wrote, the tsar attacked a soldier with a sword, grimacing and physically shaking. (At the time, Peter was experiencing powerful seizures that only his wife and successor, Catherine I, knew how to stop.)

Peter died in 1725, but researchers still debate the reasons for his behavior. Nikolay Pukhovsky, a contemporary psychologist, suggests epilepsy. Other specialists, quoted by the writer Boris Akunin, speculated that the tsar had Tourette syndrome. Akunin noted that neither of these diseases impairs “intellectual activity,” but they certainly made Peter’s life difficult.

Apart from neurological ailments, the emperor also dealt with asthma, requiring regular visits to mineral springs for treatment. His death, however, was caused by kidney disease that worsened after Peter had saved several sailors from a sinking boat.

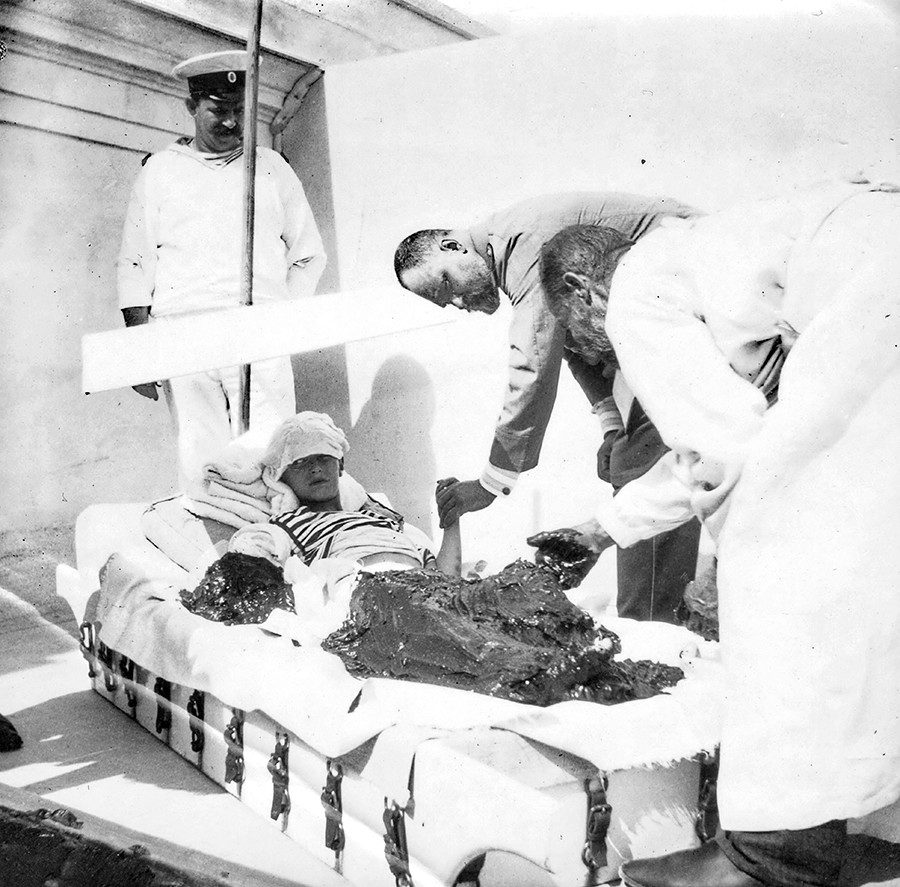

Alexei, son of Tsar Nicholas II: hemophilia

Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich of Russia during a mudbath treatment probably to cure his hemophilia at Livadia, Crimea.

Public domainAlexei Romanov (1904–1918), the only son of Russia’s last tsar, Nicholas II, never fulfilled his destiny of ascending the throne. That prospect, however, was always fraught due to the tsarevich’s serious illness — hemophilia, which he inherited from his mother, Alexandra, a granddaughter of England’s Queen Victoria.

The condition meant that every cut or bruise young Alexei received was potentially life-threatening, as his blood could not clot properly to stop bleeding. Nicholas had two guards follow his heir everywhere, but even this couldn’t avert all risks. Several times in his life Alexei suffered injuries that put him on the verge of death.

In 1917, when Alexei was 12, a doctor to the royal court stated that hemophilia made the tsarevich “unlikely to live for more than 16 years.” The question of whether the boy might have outlived that prediction was rendered moot a year later: In July 1918, a month shy of his 14th birthday, Alexei was killed along with the rest of the royal family by Bolshevik revolutionaries.

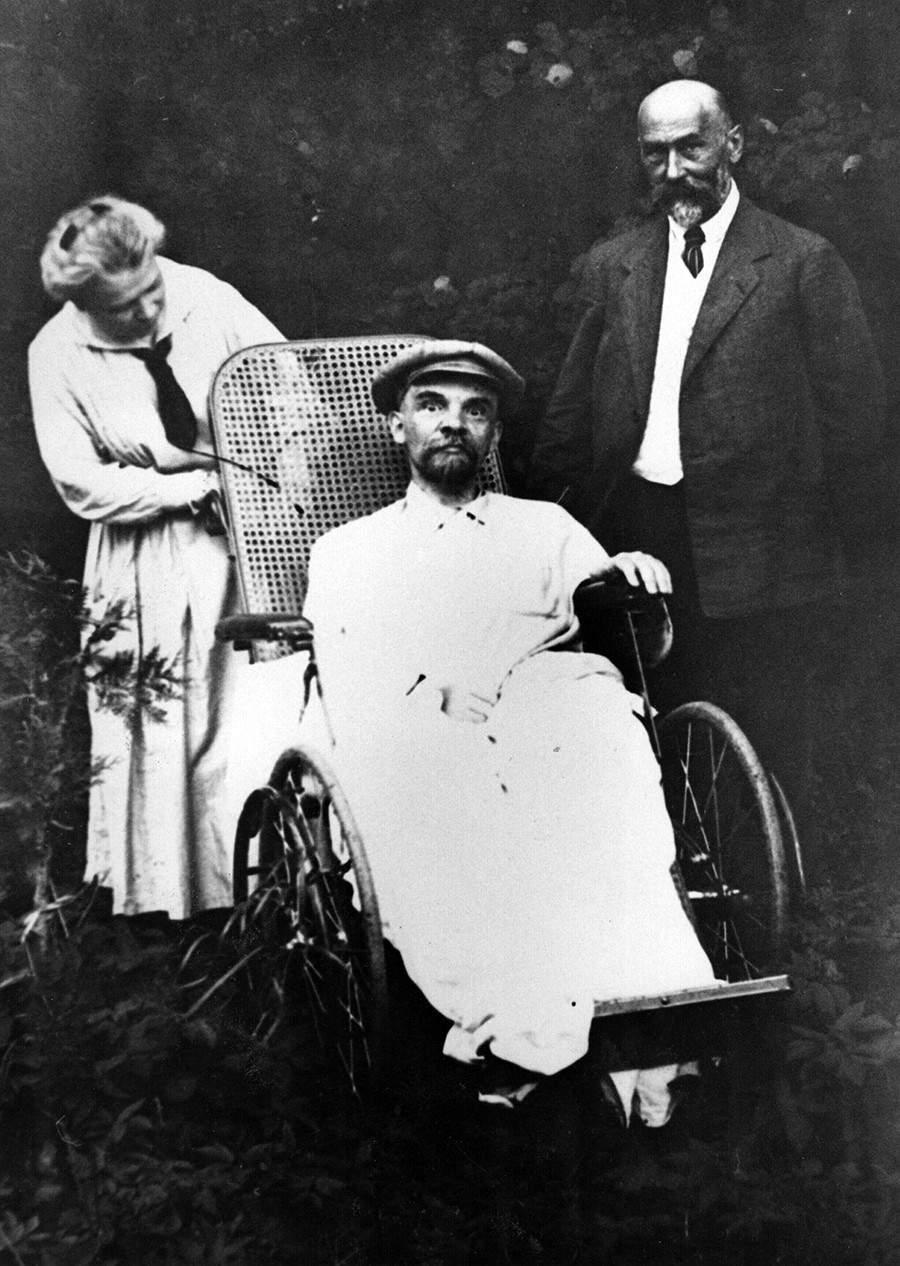

Vladimir Lenin: progressive atherosclerosis

Vladimir Lenin in his Gorky residence, in a wheelchair, months before his death.

Getty ImagesHard-working and energetic, the leader of the October 1917 revolution burned out in less than two years from a mysterious disease. He suffered his first stroke in May 1922, causing paralysis and loss of speech — humiliating for the highly active communist revolutionary.

Throughout 1922, Lenin managed to recover and returned to work. But the following year he had to leave the Kremlin and his duties. He spent months at his residence in Gorky, his health rapidly deteriorating. The best doctors, including some invited from Germany, could not determine what was ailing the Bolshevik leader.

As the

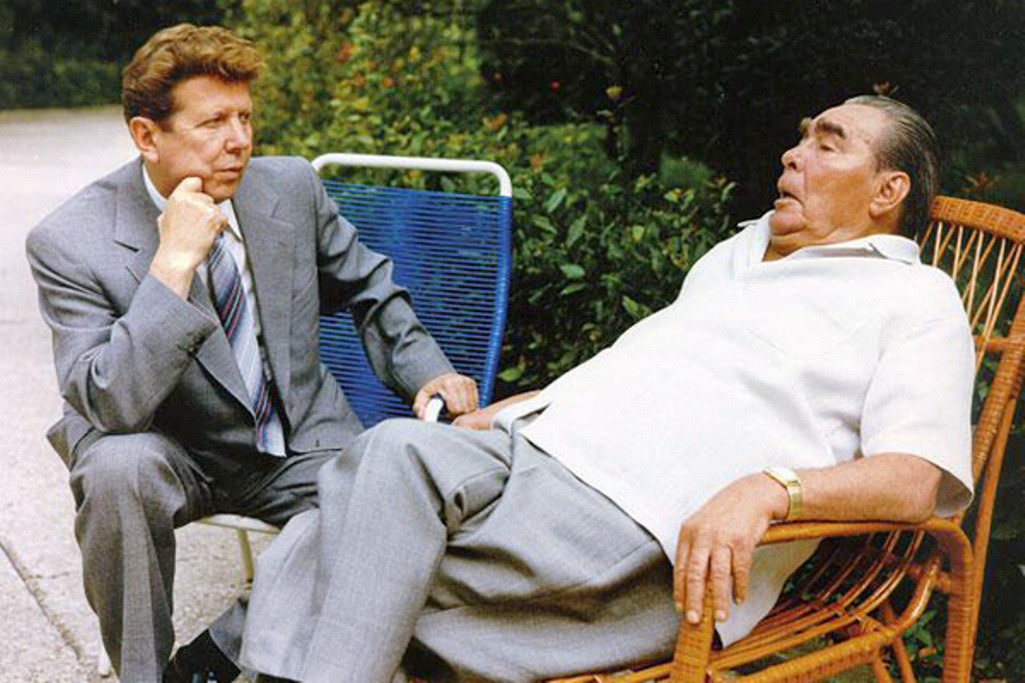

Leonid Brezhnev: problems with nervous system and heart

For years Leonid Brezhnev, sick and constantly exhausted, was accompanied everywhere by his private doctor Yevgeniy Chazov (L).

Archive PhotoThe Soviet Union’s longest-serving general secretary saw his health deteriorate during the last of his 18 years in office. Seeing their leader on television mumbling and barely able to walk, Soviet citizens made jokes about Brezhnev (“He rules the country unconsciously”). What many didn’t realize was that Brezhnev was sick long before his symptoms started to show.

“Metaphorically speaking, if he had worked as a postman, not a politician, he would have lived longer,” the historian Viktor Denninghaus notes. According to him, Brezhnev had his first heart attack in 1951, more than a decade before heading the Communist Party. Years of working after hours, chain-smoking and constant nervous tension also took their toll. From the late 1970s, he couldn’t sleep without pills, which also damaged his heart.

Perhaps Brezhnev would have gotten better if he had retired, but he didn’t consider that option. “He didn’t have enough courage to retire and had to remain the leader until his last days,” the historian Andrey Savin explains. Brezhnev died in his sleep in November 1982, age 75, from yet another heart attack.

If you enjoy stories concerning royalty, here’s a bunch of articles on the House of Romanov. And in case you prefer the Soviet history – here is a feature concerning the power struggle after Joseph Stalin’s death.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox