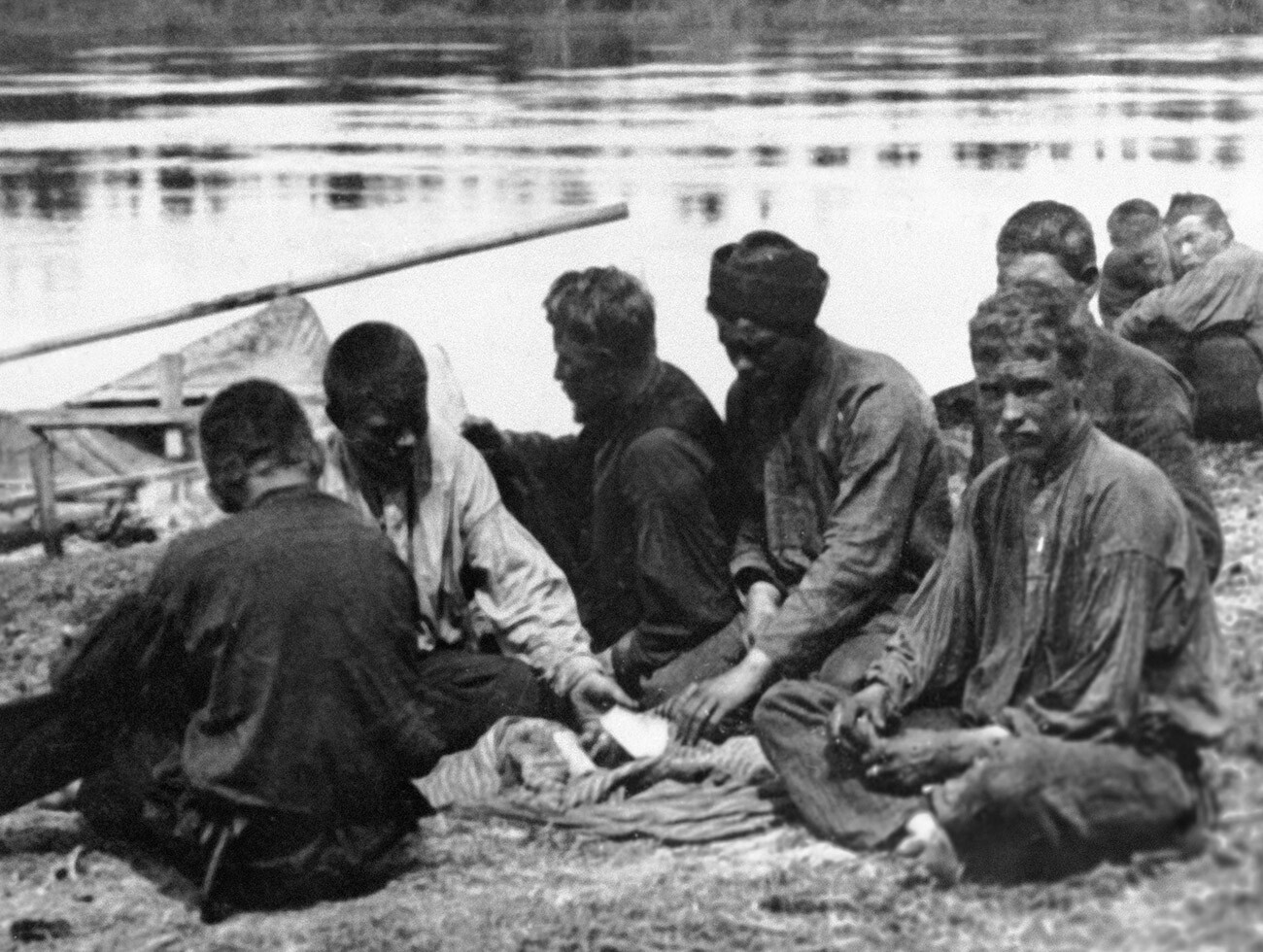

Floating prisons represented some of the darkest pages in the history of the Russian Civil War. They were cargo barges in which hundreds of people were crammed together in terribly overcrowded spaces, suffering from unsanitary conditions, disease and harsh treatment by guards. It is not for nothing that these overcrowded prison ships, shuttling along the country’s rivers, became known as ‘death barges’.

Both the Reds and their opponents, the Whites, used barges converted into prisons for criminals and prisoners of war. It was much more difficult to escape from them than from prisons on dry land; also, fewer people were needed to guard them.

Each of the two sides overtly accused their adversaries of taking the POW ships out to sea or to the middle of a river and deliberately sinking them. However, there is no documentary evidence that such mass executions took place. But, even without them, the ‘death barges’ were truly nightmarish places.

This is how doctor Kononov, who found himself on the Volkhov barge used by the Whites, described what he saw there: “All the inmates were crammed into a shockingly confined space and the hatches - the only source of air and light - were nailed shut and not opened for days at a time. The prisoners never received any food other than a piece of bread… The entire population of the barge had typhus and dysentery. The sick would defecate where they lay and their feces would ooze onto those below them. The dead lay mixed up with the living for several days at a time… The festering wounds of those who were still alive and the noses and ears of the dead were crawling with maggots. An unbearable stench overwhelmed everyone who approached the hatch: People would be immured there for weeks…”

The pieces of bread that the prisoners received were often covered in mold of every color of the rainbow. At warm times of the year, it quickly turned into a decomposing mess. There was always a shortage of clean water and people scooped up “water from overboard”, which, in turn, contributed to the spread of intestinal infections.

It was possible to get food from the guards, if a prisoner had anything of any value on him. Sometimes, people would give their only pair of boots or trousers for a stale rusk.

At the same time, the guards didn’t stand on ceremony whatsoever in the way they treated the prisoners in their charge, resorting to physical force at every opportunity. In some cases, they could even end up killing them. The bodies of the poor wretches who were shot or stabbed with bayonets were simply thrown overboard.

Despite the fact that it was almost impossible to escape from the ‘death barges’, such attempts were still made. For instance, on a hot day in July 1919, the captives kept on the above-mentioned Volkhov barge, traveling down the River Tura near the city of Tyumen, made a daring attempt to escape.

The barge housed 160 criminals and 900 Red Army prisoners of war at the time, including about 400 Hungarians, who had been fighting on the Bolshevik side. The decision to escape was prompted by a rumor that the Whites intended to sink the barge along with all of its ill-fated passengers.

When the two hatches to the hold were opened and the prisoners began to be led out on deck to go to the toilet, someone shouted “hooray”, which was a prearranged signal. At the stern end, they succeeded in disarming and killing some of the guards, but, at the second hatch, the attempt failed.

Realizing they could not overcome the guards, the prisoners began to jump into the water under a hail of bullets, but only a few of them made it to shore. Once the prisoners who had come out on deck were driven back into the hold and the situation was brought under control, the guards shot several dozen men as punishment and deprived the rest of food for three days.

The captives on a barge that the Whites had moored at the settlement of Golyany not far from the town of Sarapul had much better luck. Learning that around 400 captive Red Army soldiers were on board, Commander of the Volga Flotilla Fyodor Raskolnikov decided to attempt a daring ruse.

On October 16, 1918, the ‘Prytky’ destroyer headed towards the enemy position pretending to be a White army ship. Disguised Soviet sailors told a reception party from the barge that they had arrived to move it to a different location. In the end, it was the sheer confidence with which they acted that helped them carry out their plan.

When the barge had been towed a considerable distance from Golyany, the Bolsheviks attacked the guards and quickly disarmed them. “The hatch began to open. Everyone stood back…” POW Vikenty Karmanov recalled. “A sailor looked through the hatch and asked: ‘Lads, are you alive there?’ and threw in a loaf of bread. No words could describe what happened after that! People started shouting ‘Hooray!’, clapping and many could still not believe that their own side had come to rescue them.”

For his part, Yevgeny Freyberg, a member of the ‘Prytky’ crew, recalled that “seeing these emaciated and exhausted people was a terrifying sight. They looked as if they had climbed out of their graves…”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox