"Every yardkeeper is obliged to point out this place to everyone – however, these should be avoided, as the places pointed out are mostly unkempt. It is more convenient to go into the first hotel, giving the doorman 5 to 10 kopecks for a tip. A public lavatory, quite clean – on Ilyinka across from the Exchange, behind the Novotroitskaya hotel on the narrow Pevcheskaya line, in the passageway, with the descent to the basement floor" – this is what journalist Vladimir Gilyarovsky wrote in a guidebook to Moscow in 1881.

As you can see, it was very difficult to find a public toilet in Moscow in those times. In fact, there were no public loos in Russian capitals until the 1890s.

Sukharevskaya square in Moscow, with the Sukhareva Tower in the background, late 19th century. Note the dire condition of the street, covered in mud and feces.

pastvu.com/Public domainThe first equipped restrooms in Russia were, of course, at the imperial premises. There were latrines in the palace of Ivan the Terrible in Kolomna, in the palaces of Alexei Mikhailovich in Izmailovo and Kolomenskoye. In 1710, in the palace Montplaisir in Peterhof, the first Russian latrine with a flush was made for Peter the Great.

By the end of the 18th century, properly equipped restrooms appeared in the houses of the nobility. They were described in detail by Daikokuya Kōdayū, a Japanese merchant who had been ship-wrecked in the Aleutian islands and then was forced to spend ten years in Russia in the 1790s until Catherine the Great allowed him and his crew to return home. Daikokuya looked at Russian life with the fresh eyes of an outsider.

"Even in four- and five-story houses there are privies on every floor," is how Daikokuya described the everyday life of St. Petersburg, which he visited on several occasions. "They are arranged in a corner of the house, fenced from the outside with a two-three-layer wall, so that the odor wouldn’t percolate through. A pipe like a chimney is built at the top and the bad odor comes out through it."

Daikokuya writes that the height of the wooden seat in these latrines was about half a meter, and explained it as follows: "in Russia, pants are put on very tight, so it is uncomfortable to squat, as we [Japanese people] do.”

Zolotars (sanitation team) in the 1910s

Public domainHe also noted that houses had latrines with several holes at the same time, and rich people had stoves in their latrines to keep warm. He cites the city fee for emptying the cesspools, where all the waste was eventually poured – 25 rubles a year. By the standards of the time, this was a lot of money, which only the rich could afford.

Cleaning of cesspools was carried out by teams of zolotars (sanitation teams) who first appeared in Catherine the Great’s time. They traveled around certain parts of the city and took out the stinking sludge in barrels – for this service a fee was charged. Most citizens tried to save money by pouring their sewage into the street, or into ditches behind the fence, or wherever.

Historian Vera Bokova writes that in the mid-19th century, "absorbing wells" were popular in Moscow. They are described by Moscow theater director Yuri Bakhrushin: "Wells in the ground, which had the ability to suck into the soil everything that fell into them. Thanks to this, owners of plots were spared the expense of removing waste from their property. All this disgusting dirt was dumped into the well and ‘disappeared.’ And then the owner didn't care that it later went into the underground springs that fed the numerous drinking water wells.”

In apartment buildings, there were rooms with latrines located on public staircases, which made the hallways stink, especially in summer. In the courtyards, there were wooden booths above the cesspools – for those who lived on the first floor and in the cellars, as well as for yardkeepers and doormen.

By the second half of the 19th century, water closets were available in some of the most expensive hotels and in the homes of the rich. But what could a common person do if he needed to go to the toilet in the street?

"Travel through all Western Europe, and you will not see such scenes as occur in St. Petersburg every day and in full view of everyone. A gentleman stands in the middle of the street and, in full view of all the passengers in passing carriages, satisfies his needs. In London, such a gentleman would have been taken to the police station as an offender; but how could such a thing be done to an inhabitant of a city in which there is no necessary commodity of city life – urinals? Moreover, we probably know that if a decent passerby goes for a minute or two in an alleyway, the yardkeeper drives him out into the street," wrote Ivan Goncharov in 1864. The great writer was as much a St. Petersburger as any other, and he himself, as he admitted in a letter, was sometimes forced to "publicly, in the streets, to discover human infirmity".

The first public toilet, reports historian Igor Bogdanov, appeared in St. Petersburg in 1871 at the Mikhailovsky Manege. "It had two urinals, two water-closets and a small room for a watchman; the toilet was abundantly supplied with water, heated by a cast-iron stove." Heating was mandatory for street toilets, otherwise the water would freeze in winter.

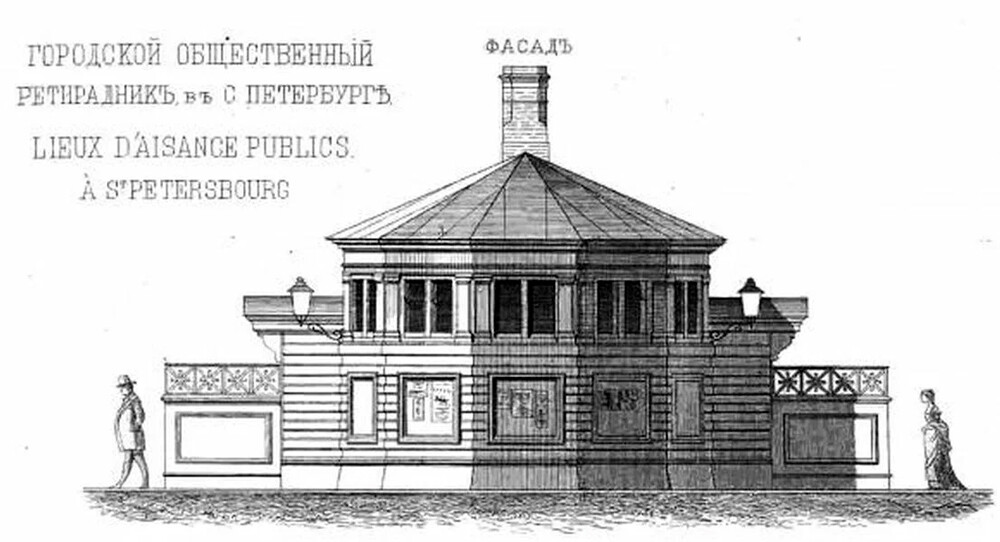

A project of a wooden booth of a public toilet in St. Petersburg

Public domainSoon, five more street booths were built according to the design of the city architect Ivan Metz. They had separate compartments for women and men, and a room for the watchman. They were fenced in and trees were planted around them. Still, wrote architect Metz, "many people prefer to stop outside, near the booth, rather than go straight through the doors! Alas! It takes time, too, it takes years to get accustomed to good manners." These toilets were free of charge, maintained by the city government.

Things in Moscow were dirtier – the first full-fledged public restrooms began to appear only in the late 1890s. Before that, only booths were installed, mostly in large markets, where it was quite indecent to empty oneself in public on the street. But what about the rest of the streets? As Nikolai Davydov, a Muscovite, recalled, "the places where cab drivers, innkeepers, taverns, common people's taverns and similar establishments stood and, finally, all street corners, even if boarded up from below, various nooks and crannies (and there were a lot of them!) and covered gates of houses... were hotbeds of spoiled air".

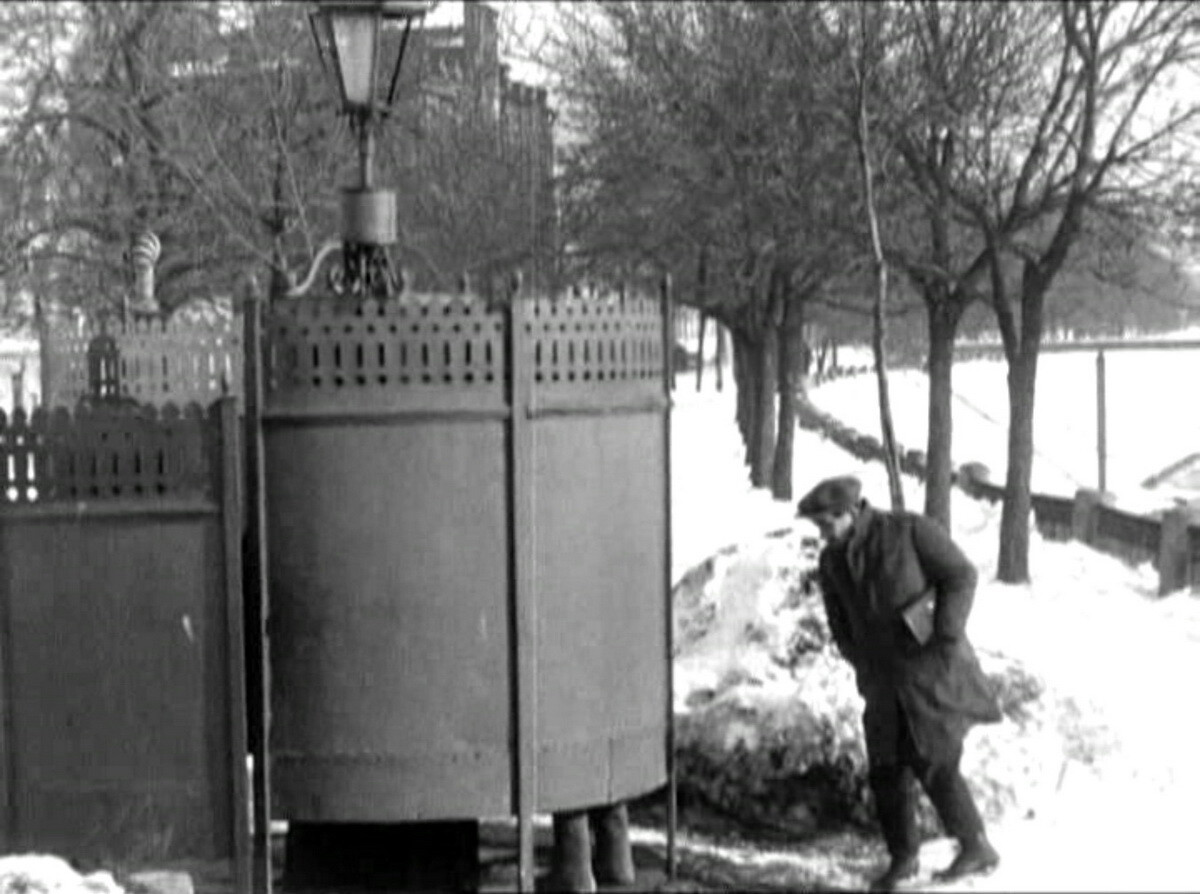

Since the 1880s, public urinals – simple grates over cesspools made in the ground and enclosed by screens (like changing booths on beaches) – were built on some public squares. And only at the beginning of the 20th century did stone public restrooms appeared, including three underground ones – on Teatralnaya, Sukharevskaya and Pushkinskaya squares.

Shot from the stairs of the Sukhareva Tower, this photo shows two entrances to the underground public toilet on Sukhareva square (center of the photo)

G. Brunstein/pastvu.com/Public DomainHowever, the main problem of public latrines in tsarist times was getting rid of waste. After all, even in Moscow and St. Petersburg, both the most populated cities of the empire, there was no sewerage system until the end of the 19th century.

In Moscow, a sewer system began to be built and developed only in 1893 when Lublinskiye irrigation fields appeared, where sewage was filtered through the soil. And still for a long time the old capital was surrounded by a "ring of sewage", which the historian Solovyov compared to the rings of Saturn – because Moscow zolotars transported and dumped waste outside the city. When approaching Moscow, passengers of trains closed their windows because the odor was so strong. Zolotars continued to roam the streets of the capital until the 1930s.

The public lavatory on the Devichye field in Moscow, one of the oldest in the capital.

S. G. Velichko/pastvu.com/Public domainIn St. Petersburg the situation was unfortunately "easier" – the city is crossed by rivers and canals, where it was possible to pour the sewage. As historian Igor Bogdanov writes, "Basically, in the 18th and 19th centuries, sewage, as well as the effluents of industrial enterprises were discharged without filtering into rivers and canals and taken to the Gulf of Finland. Pollution of city waterways and clogging of street canals forced the government as early as 1845 to forbid connecting yard cesspools to street pipes".

Some homeowners, writes Bogdanov, used the city-wide rain sewer system to get rid of their waste. Running right through the streets, this rain sewage system first appeared in St. Petersburg in the 18th century. As a result, the intersections of the streets of St. Petersburg throughout the 19th century sometimes became an accumulation of human and horse excrement. The government banned the pouring of pots into the "storm drain" starting in 1860. However, by 1884 it became clear that the ban was being widely ignored. So, the government ordered at least to install grates on the drain pipes to filter solid waste, but this was to no further avail.

A public urinal in Moscow, the 1920s

Yakov Protazanov, 1924, MEZHRABPOM-RUS'Alas, despite all efforts and several projects, a general sewerage system was never built in St. Petersburg under the tsars. One of the consequences was the terrible cholera epidemic that started in Petrograd in 1918. A full-fledged sewerage system in St. Petersburg began to be built during the time of Soviet power.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox