At the beginning of the 17th century, the population of the Tsardom of Muscovy was prohibited from helping the ‘nemtsy’ (a general term for all foreigners) to find routes leading to Siberia. A “wicked death” and ravaging one’s home “to the ground” was the punishment. To this extent, the freshly-ascended-to-the-throne after the ‘Time of Troubles’ Mikhail Romanov didn’t want to allow foreigners deeper into the country.

The ‘Time of Troubles’ offered Western countries an opportunity to gain at Russia’s expense. This period lasted from 1598, when the Rurikid dynasty ended, until 1613, when Tsar Mikhail ascended to the throne – the first from the Romanov dynasty. But, it’s one thing to capture border regions in the West, like the Swedes and the Polish did, and completely another to try and colonize the north-eastern lands of this giant country like the English.

Mikhail Romanov

Public domainBy the beginning of the 17th century, the English felt in charge in the Russian North. Appearing at the mouth of the Northern Dvina River in 1553 for the first time, in 1555, they founded the ‘Moscow Company’. A couple of years later, they opened one of the trading posts in Pomorye (near the White Sea shores); and, in 1569, they received permission from Tsar Ivan the Terrible to conduct duty-free trade across the entire Tsardom of Russia.

Taking advantage of this, English merchants began to export linen, ropes and hemp ropes, resin, tar, lard, mast timber, furs, wax, hides, leather, potash, oil and caviar from Arkhangelsk and Kholmogory. In 1611, during the ‘Time of Troubles’, they planned to conduct talks with the locals about signing a deal on the conditions of sovereignty or protectorate. But, they didn’t make it in time. The election of Mikhail Romanov as Tsar put an end to the ‘Time of Troubles’. The English, however, were in luck: they hadn’t yet gone through with the realization of their plan. It remained secret and foreign diplomats saved their faces before Moscow.

But, English appetites didn’t end with the Russian North. Their goal was to penetrate Siberia.

Siberia offered incredible trade and economic perspectives. Firstly, the route to India and China went through there. Secondly, it was a potential center of foreign trade in itself. Thirdly, at the beginning of the 17th century, the natural wealth of Siberia was already known. Finally, access deep into the Tsardom of Muscovy would be gained not just by merchants, but also by religious missionaries, as well as spies and a variety of adventurers. The infiltration of Siberia by the English would cause Russia even greater damage than giving them concessions for exporting goods from the Russian North.

The problem was, Moscow found it hard to straightforwardly refuse London’s requests to grant it access to Siberia: the English loaned money to the temporary tsars during the ‘Time of Troubles’ and acted as intermediaries in peace talks between Mikhail Romanov and Sweden and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Russian Tsar Mikhail Romanov had to stall time in order to gather some funds to cover the debts with the English and not to let them deep into the country at the same time. That’s when people were prohibited from showing foreigners the route to Siberia on pain of death.

It was now in Moscow’s interests to seize initiative in Siberia. This opened the opportunity for control over the entire trade and for a more active collection of ‘yasak’ ((a Turkic word that was used in Imperial Russia to designate fur tribute exacted from the indigenous peoples) from the locals and merchants. For that, they needed to build military forts in Siberia – ‘ostrogs’ – as well as prevent possible bypassing of customs posts.

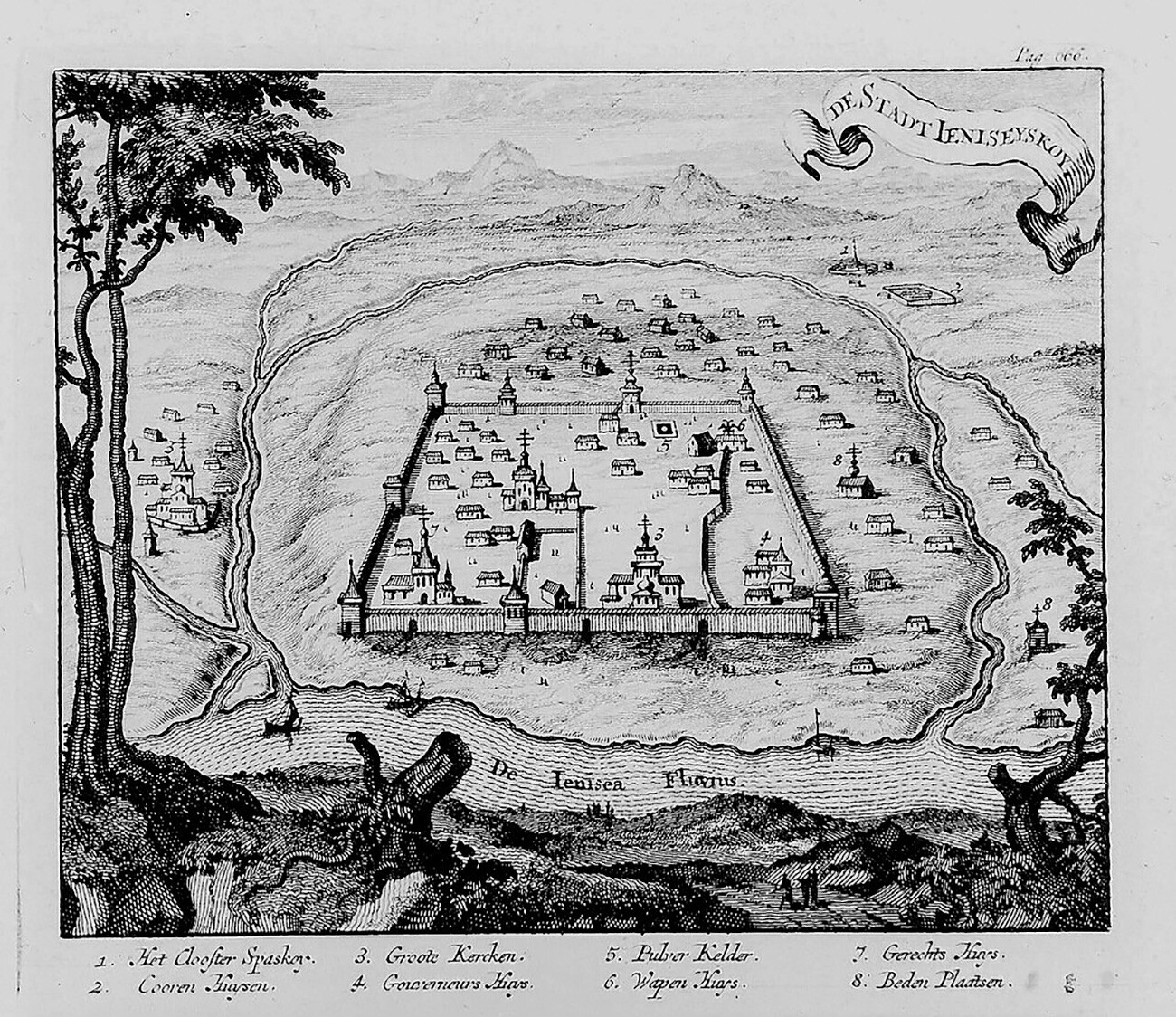

The Yenisei ostrog at the end of the 17th century

Public domainTo achieve both goals, the tsar decided to fully close down the Mangazeya Sea Route in 1619.

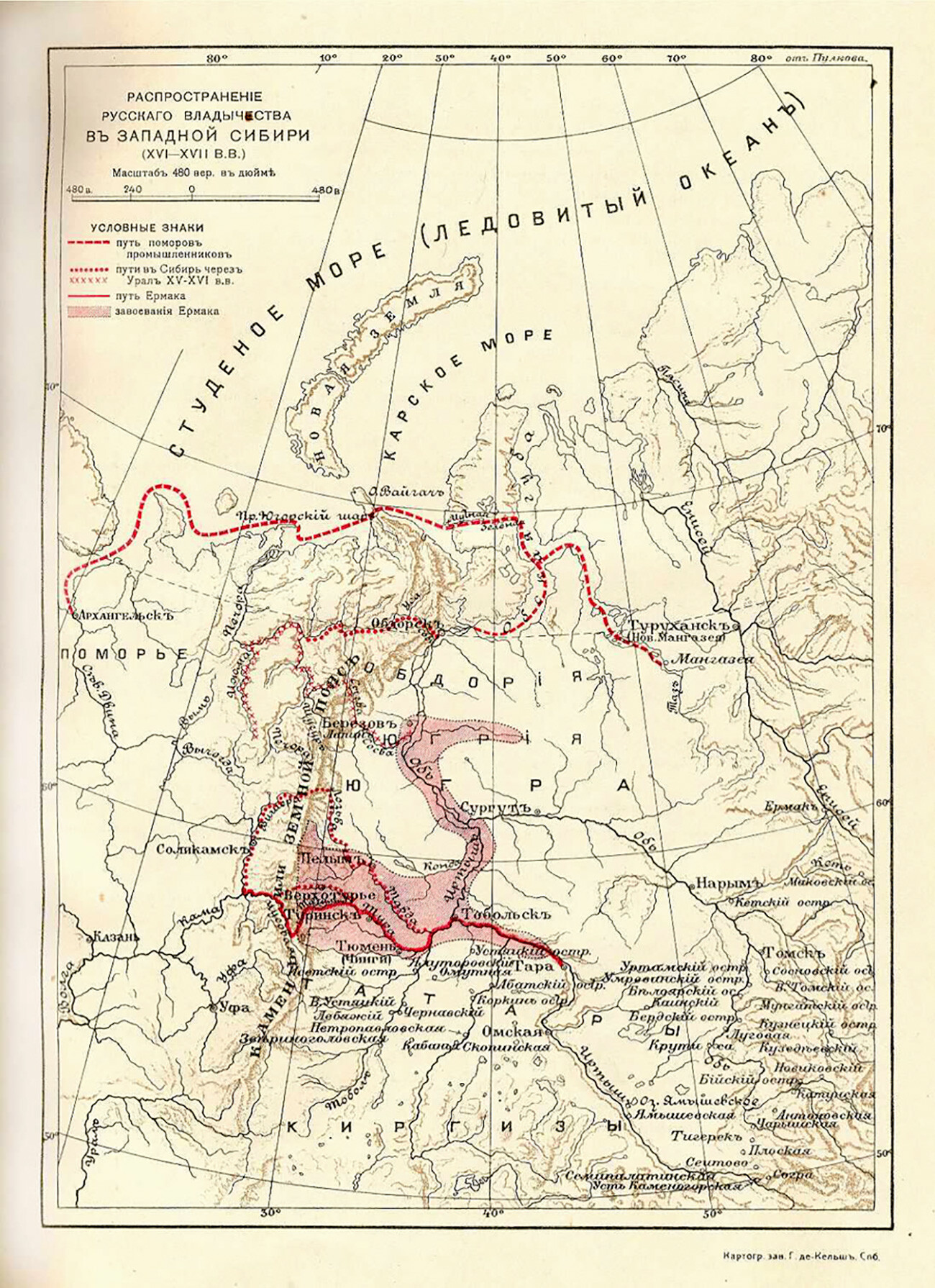

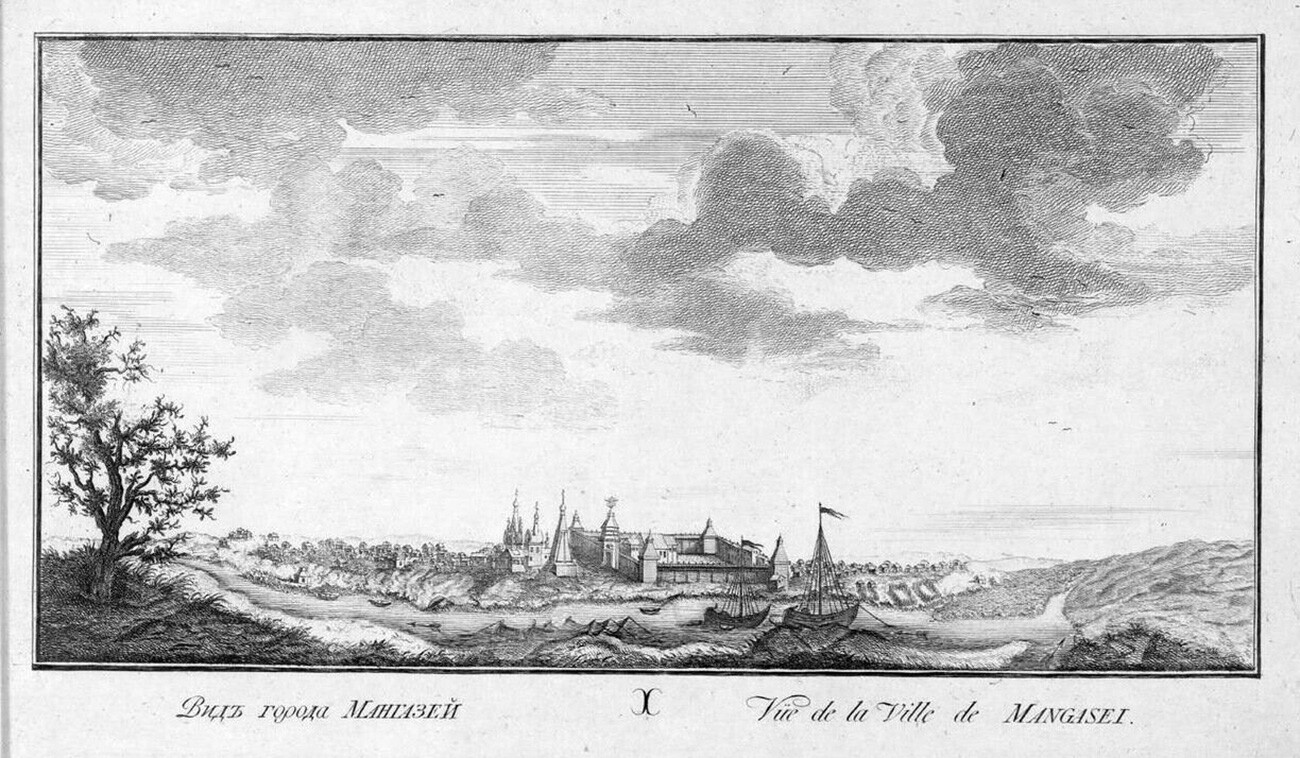

The Mangazeya Sea Route was an important trade route that formed over the course of the 16th century. It began at the mouth of the Northern Dvina River and went through the White Sea, the Barents Sea and the Kara Sea to the Taz Estuary and further along the Taz River to the city of Mangazeya (it was located 200 kilometers directly north-east from modern Novy Urengoy).

Map of the conquest of Western Siberia in the 16th century

Public domainThe route also included overland parts on the Yamal Peninsula: they were covered by portage. Fur – aka ‘soft gold’ - was exported en masse from Siberia along this route; leather, gunpowder, salt, lead, grain and other goods were all imported.

The Portage

Nicholas RoerichMangazeya grew out of a simple Pomor trade post, founded at the end of the 16th century. In time, it received ‘ostrog’ (military fort) status and, later – ‘posad’ (urban settlement) status. In 1603, a ‘gostiny dvor’ (trade center) appeared there – a key infrastructure for wholesale trade. Besides, Mangazeya became the center of yasak collection from all the nearby and remotely living native peoples.

As the city grew wealthier, it attracted more and more attention from Moscow. But, unlike the Ob River and its tributaries, the sea route from Pomorye to Mangazeya couldn’t be controlled as tightly. That meant losses from unpaid taxes to the treasury. There were also great concerns that foreign ships would appear in the Kara Sea and that outsiders would start a trade and economic expansion into Siberia. So it was decided to cut off the route to Mangazeya.

“And from the old route from Mangazeya by the Taz River to the Zelenaya River, then to portage, then to the Mutnaya River, then to the Kara Estuary and by the open sea to the city of Arkhangelsk and to Pustozero (a city on the Pechora River), the trade men and industry men were banned, so outsiders wouldn’t learn the path from Pustozero and from the city of Arkhangelsk to those parts, to Mangazeya, and so they wouldn’t travel to Mangazeya,” the tsar’s edict said.

Instead, it was ordered to travel to Mangazeya only by a land route through the Urals. That was significantly longer and harder – meaning unprofitable.

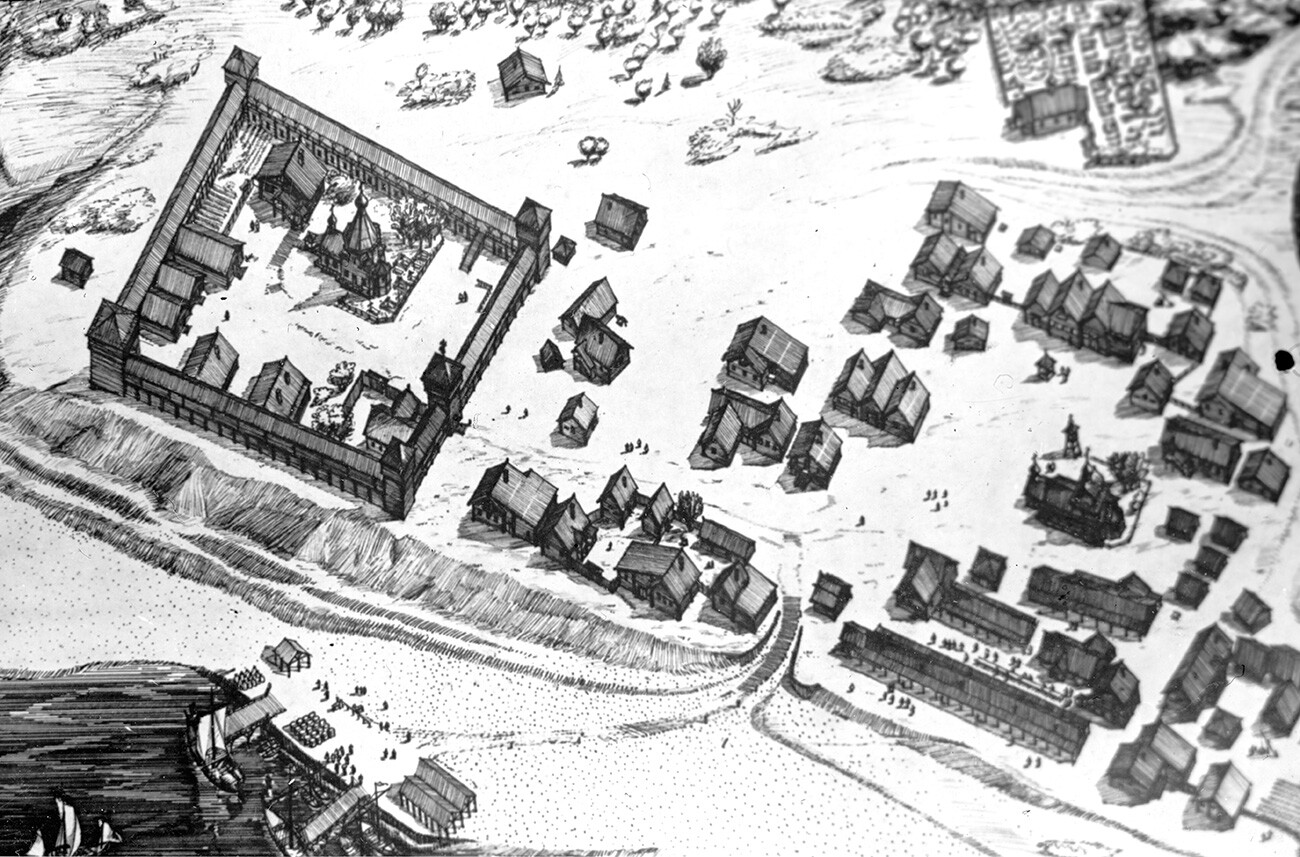

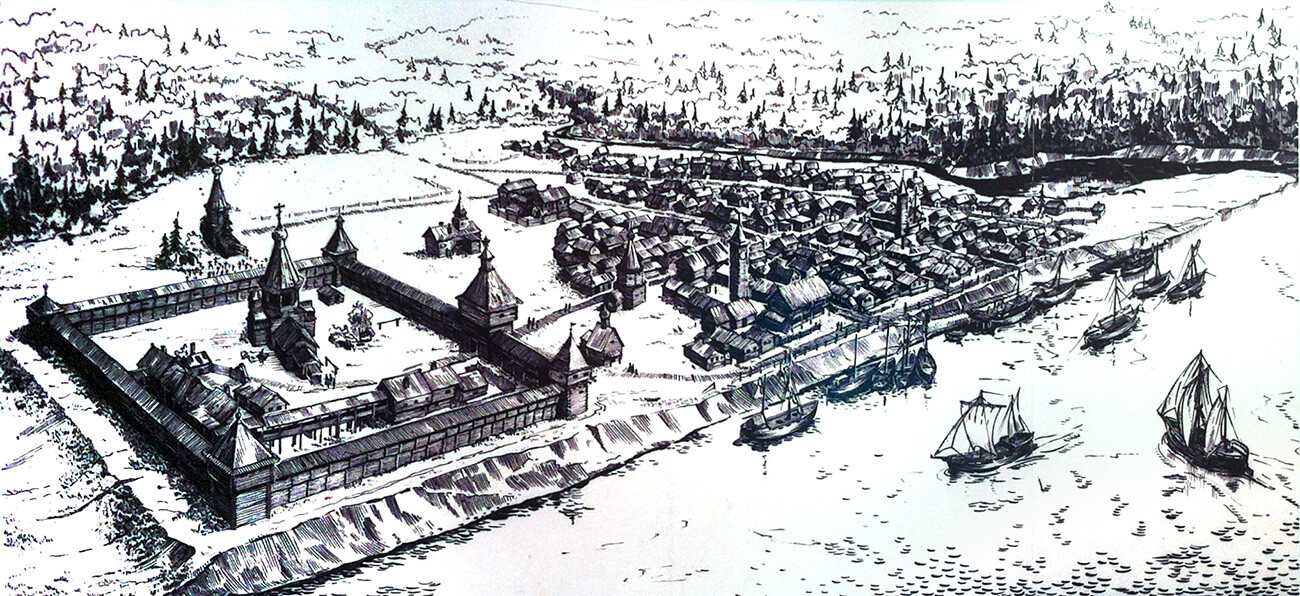

The Mangazeya ostrog with a settlement. Reconstruction based on M. Belov research

M. BelovThe shutdown of the route completely severed sea links between Pomorye and Siberia. As a result, Mangazeya slowly faded and disappeared from maps after the 1643 fire.

Citizens didn’t rebuild in the place that had lost its trade significance and, instead, settled in Yeniseysk and Turukhansk, which was later renamed New Mangazeya.

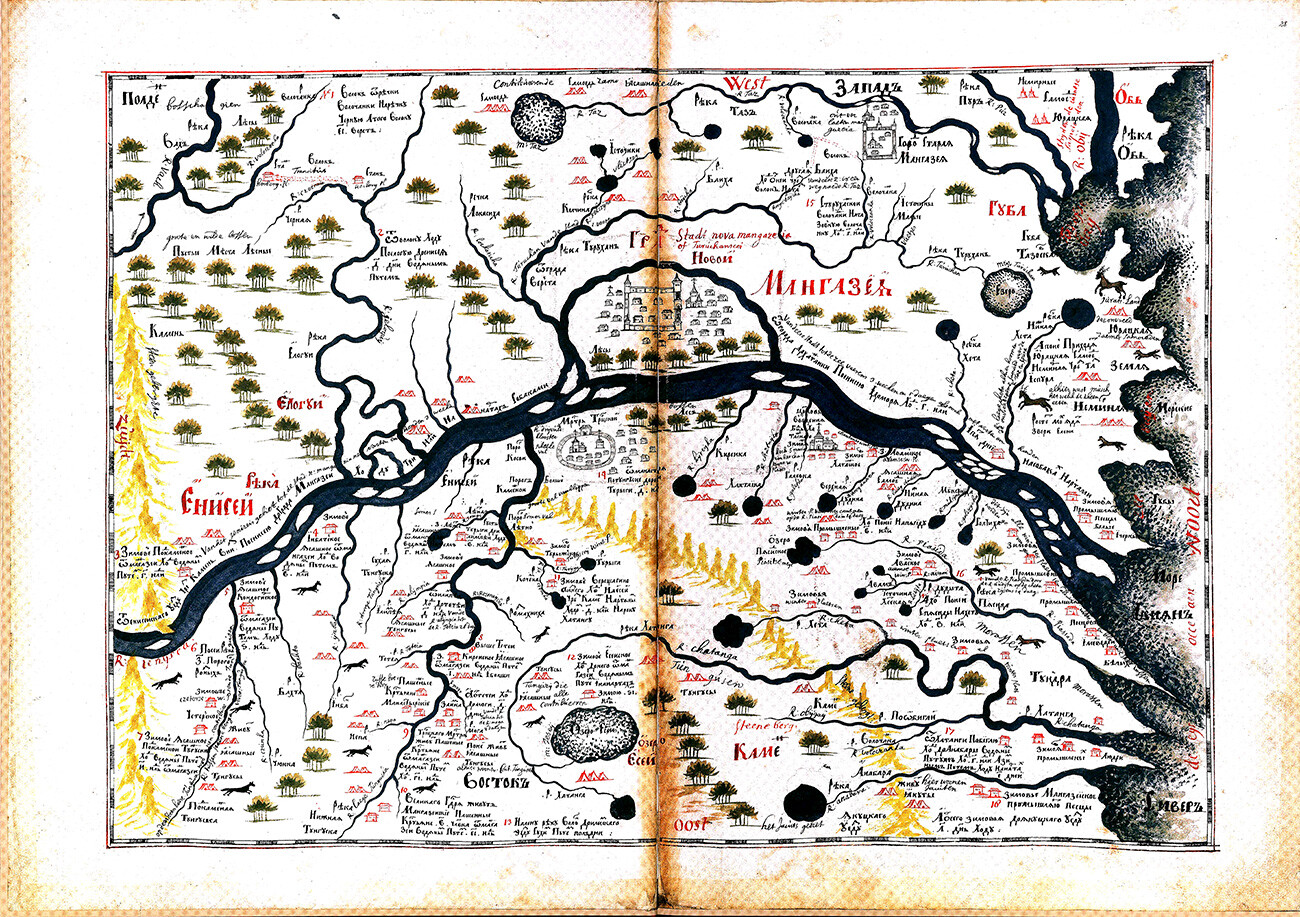

Map of Novaya Mangazeya (modern Staroturukhansk) with the surroundings of the late 17th century from the "Drawing Book of Siberia"

Semyon RemezovIn Tsarist Russia, the information about the first Mangazeya survived in scarce documents and folk tales. In time, it acquired the aura of a legend. Real evidence of the existence of the wealthy trade city emerged in 1946, after an archaeological expedition by the Arctic Research Institute.

Items found at the site of Mangazeya

Donat Sorokin / TASSFor two and a half centuries, only exploration expeditions traveled along the Mangazeya Sea Route. From 1877 onwards, episodic trade caravan convoys began, which exported agricultural produce and raw materials from Siberia to Arkhangelsk through the Kara Sea. But, without a seaport and navigational infrastructure, only half of them were successful.

Today, the Mangazeya Sea Route has become a fragment of the Northern Sea Route. In 1932, it was covered by the icebreaker ‘Alexander Sibiryakov’ for the first time in one trip: it sailed from Arkhangelsk all the way to the Bering Strait.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox