Meet Yermak, the guy who conquered Siberia

Yermak, Cossack Ataman, at the head of his troops

Getty ImagesIn a galaxy far, far away, Khan Kuchum would be Dark Sith. Merciless, cunning and elusive, this man was never beaten or captured, even after losing his brother, two sons, and two grandsons to a devastating Russian attack. It was he who involuntarily brought to life the Russian exploration of Siberia – but also he who killed Yermak, Siberia’s first conqueror.

A man without a past

Unknown artist, Portrait of Yermak, XVIII century, oil on canvas

Global Look Press“Very courageous, and human, and notable, full of wisdom, flat-faced, dark-bearded, of average height, sturdy, and broad-shouldered” – the only description of Yermak’s physical appearance is the one by Semyon Remezov (1642-1721) from Tobolsk. His father knew Yermak’s comrades, who had conquered Siberia, and they had described their famous ataman (Cossack leader). But this is roughly all the information that is known about Yermak. Even his real name is still debated, and neither his birthplace nor the year he was born is known. The consensus is, however, that he was born around 1532 and came from the Arkhangelsk region.

LEGEND:

An old Ural tale says Yermak was a warlock who kept imps as his servants: “When he didn’t have enough men, he used them.”

TRUTH: Awed at the skill of Yermak and his comrades, who conquered the Siberian Khanate with only about 500 men, Russian lore endowed Yermak with supernatural abilities.

When Yermak is called a Cossack, this doesn’t imply his nationality or birthplace. In the 17th century, people who protected the country’s outskirts, but weren’t noblemen and didn’t serve in the army, were called Cossacks.

Yermak was an experienced field commander: in the Livonian War, he commanded a hundred Cossacks. In 1581-1582, he defended Pskov and took part in several other battles; but in 1582, he ended his service to the Moscow tsar’s army and headed East, to the Urals. Why?

Salt of the earth

Khan Kuchum flees from Kashlyk. Illustration from the Remezov Chronicle, late 17th century

Public domainIn 1563, Khan Kuchum killed Yediger, the Khan of Siberia, and conquered his land. The Tatars of Siberia considered Kuchum a foreign conqueror. Kuchum’s rule was cruel and oppressive, with many executions and heavy taxes. Unlike Yediger, Kuchum refused to pay Ivan the Terrible tributes.

Kuchum’s army frequently bothered the Stroganovs, wealthy merchants who made their fortune in salt production and owned multiple salt mines in the Urals. Kuchum’s Tatars attacked and pillaged the Stroganovs’ villages, taking Russian people as prisoners. The Stroganovs then hired Yermak and his gang of Cossacks to protect their lands. Yermak came with 540 Cossacks and in late 1582, started his journey from Oryol Town, the Stroganov residence in the Urals.

Yermak’s troops were traveling in war boats, packed with ammo and food. While going through forests, they chopped their way through with axes, while carrying the boats on their shoulders. Along the river path, they soon crossed the Urals and entered the Siberian Khanate.

All the while, the Cossacks fended off the attacks of Kuchum’s forces, including Mametkul, Kuchum’s nephew and his leading military commander. Yermak’s gang was so strong they easily crushed the ill-weaponed and slow Tatars. In the Battle of Chuvash Cape, Yermak’s firearms made Tatars, who were seeing guns for the first time, flee in terror; Mametkul barely escaped capture, and Kuchum himself had to flee from his capital, Kashlyk.

Death of the winner

"The Conquest of Siberia by Yermak" by Vasily Surikov (1895). Oil on canvas

Yuri Kaplun/SputnikIt’s commonplace to say that Ivan the Terrible himself sent Yermak to conquer the Khanate. On the contrary, upon learning of Yermak and his troops’ conquest of the Siberian Khanate, Ivan the Terrible panicked. The Livonian War still went on, and not in favor of Moscow, so a war with Kuchum, that Yermak’s actions could have ignited, was one of the worst things that could happen.

Ivan wrote to the Stroganovs demanding to call Yermak back at once; but at this very moment, Yermak took Kashlyk and sent his fellow ataman, Ivan Koltso, to Ivan with the message about his feat. Upon learning about Kashlyk being taken, Ivan was nevertheless delighted at Yermak’s success and sent him awards – and an order to immediately return to the Russian lands!

LEGEND:

Upon learning of Yermak’s conquest of Siberia, Ivan the Terrible was elated and sent him two expensive heavy chain mail body armors.

TRUTH:

Ivan IV did reward Yermak, but he sent him money and an expensive piece of cloth, but no chain mails.

But Yermak didn’t make it back. After time, his squad reduced in numbers, while fellow atamans were being killed. On August 6, 1585, Yermak and his 50 troops were on a scouting mission. While asleep, they fell prey to the Tatars’ attack. Yermak was killed in this skirmish. The few surviving Cossacks went back to the Russian lands.

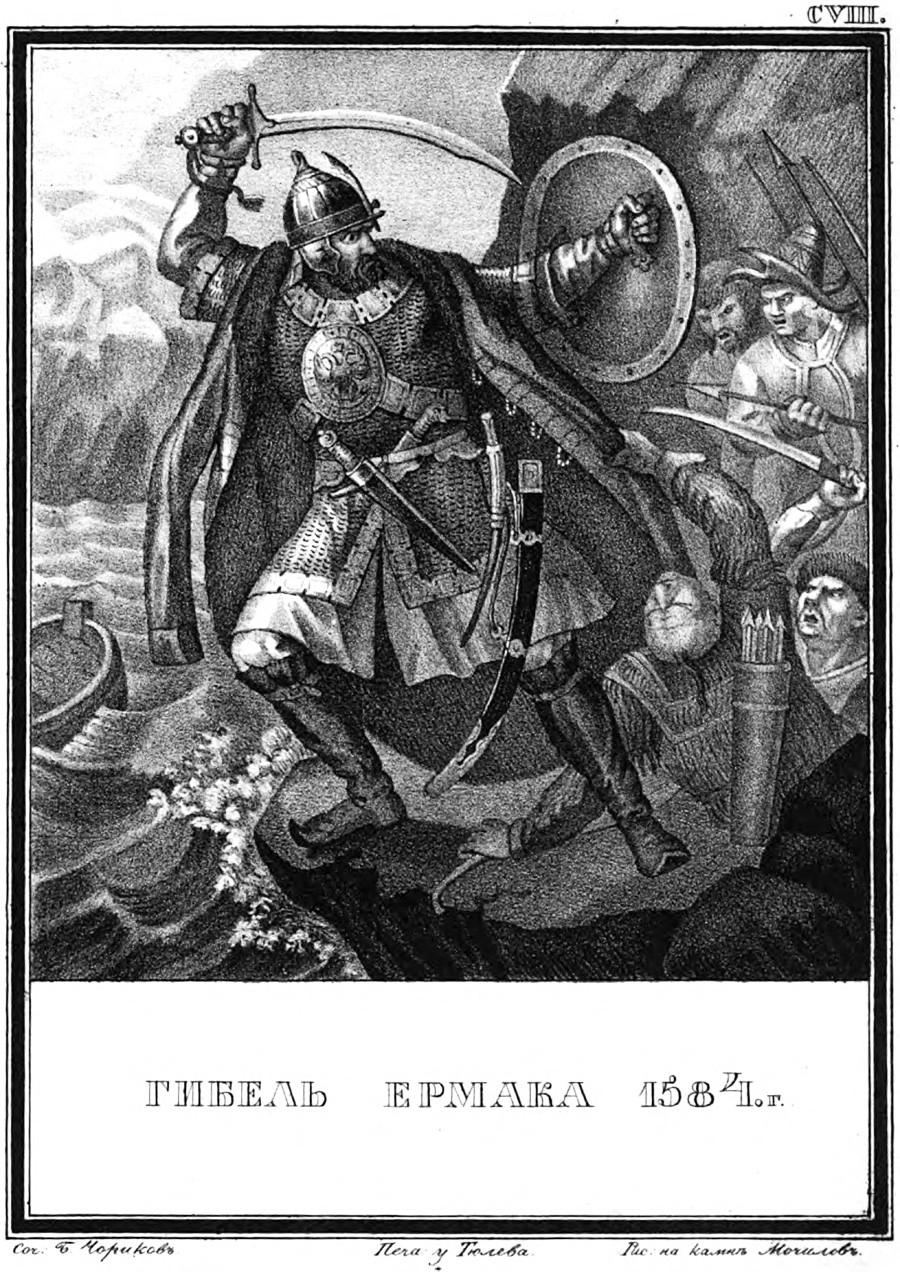

The Death of Yermak, 1584

Getty ImagesLEGENDS OF YERMAK’S DEATH:

1) The chain mail armor that Ivan the Terrible sent to Yermak became the reason of Yermak’s death: during the attack of Tatars on his camp, he fled, swimming towards the boat of his comrades, but drowned because of the heavy chain mail.

2) Yermak’s body was found by a Tatar fisherman a few days after he drowned. The Siberian Tatars gathered to look at the ferocious ataman’s body. They stabbed the body with their pikes, and it bled like it was alive; also, Yermak’s body didn’t rot. The Tatars were shocked and honored Yermak like royalty, burying him with a ceremony.

TRUTH:

The exact circumstances of Yermak’s death are unknown. His grave is lost, if there ever was one.

In 1598, Khan Kuchum’s army was finally crushed by Russian warlord Andrey Voyeykov. Kuchum’s brother, sons, and grandsons were killed, but the Khan himself managed to flee into the steppes. There is no data about the time or place of Kuchum’s death.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox