Jewish partisans in Byelorussia, 1944.

Yad Vashem"We weren't afraid of the Nazis. We were on home soil. My brothers and I were raised in the countryside. And, in the countryside, there is a simple philosophy: Why should anyone else come and take something that we have earned through hard work?" is what Aron Bielski of the Bielski brothers' partisan detachment, which operated in German-occupied Soviet Byelorussia, once quoted as saying.

It is notable that the formation was almost entirely made up of Jews. They were unwilling to die a cruel death in a ghetto or meekly submit to execution and, taking up arms, they put up fierce resistance to the Nazis.

Soviet partisans in Byelorussia.

Mikhail Trachman/SputnikIn the Soviet Union, dozens of Jewish partisan detachments fought the Nazis: The Bielski detachment was one of the largest and most effective.

The enemy occupied the Bielskis' village of Stankevichi in Western Byelorussia two weeks after the start of the war. The inhabitants learned what the Holocaust was fairly early on.

Several members of the Bielski family died at the hands of the Nazis in summer of that year, and, in early December, it became clear that the Germans intended to completely wipe out the local Jewish population. After their parents and sister were shot, the brothers Tuvia, Asael and Zus took their remaining relatives with them into the woods.

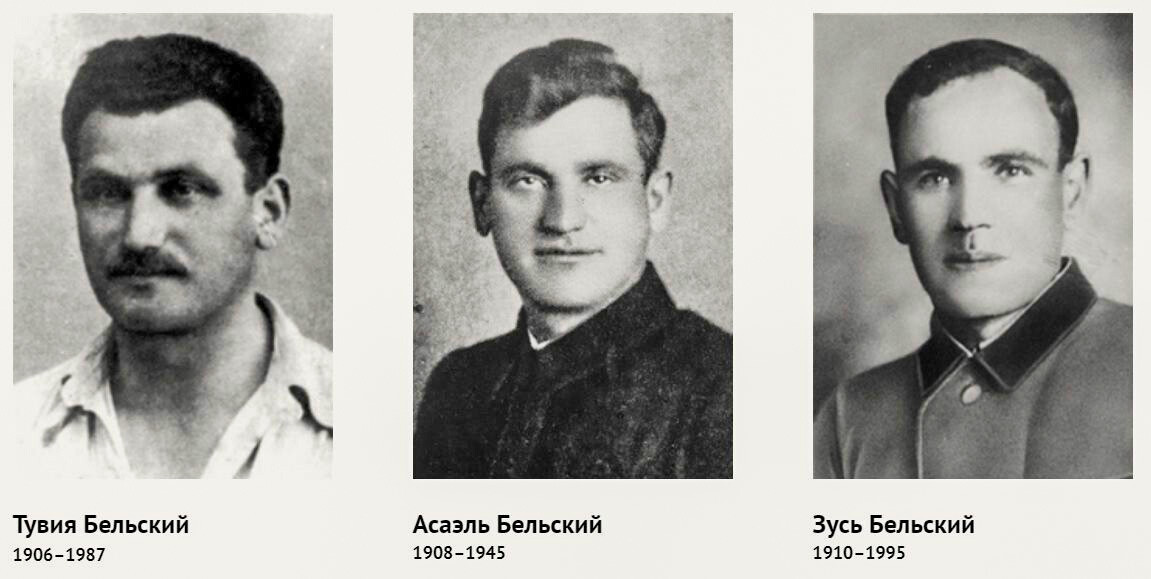

Tuvia, Asael and Zus Bielskis.

Public DomainThey were soon joined by their younger brother Aron, after he miraculously escaped death, but Zus was unable to save his young wife and new-born daughter.

Numbering a couple of dozen, the survivors set up an encampment not far from their village and were initially completely preoccupied with not dying of cold and hunger. Once they felt more settled, however, they started to rescue other Jews – they made their way into ghettos in neighboring towns and persuaded people to flee and join them.

"I don't promise you anything," Tuvia told other survivors. "We may be killed while we try to live. But we will do all we can to save more lives. This is our way, we don't select, we don't eliminate the old, the children, the women. Life is difficult, we are in danger all the time, but, if we perish, if we die, we die like human beings."

Members of the Bielski detachment.

Yad VashemAmong those who found refuge with the Bielskis were Raia (Rae) and Zeidel Kushner, the grandmother and great-grandfather of businessman Jared Corey Kushner, Donald Trump's son-in-law.

The Bielskis did not merely plan to hide in the woods. They organized a partisan detachment headed by Tuvia, the eldest of the brothers, while his brothers became junior commanders (because of his youthful age, Aron took on the role of liaising with other partisan detachments). By the Spring of 1942, the formation numbered 80 members.

Having got hold of weapons, the partisans started regularly harrying German garrisons in villages and hamlets, cutting the enemy's communications and remorselessly killing collaborators. The Nazis, in turn, mounted punitive operations against them, driving them deeper and deeper into the forest.

Doctors treat Jewish partisans at a field hospital.

United States Holocaust Memorial MuseumFinally, the Jewish fighters set up base in the very depths of the Naliboki Forest – the largest forested tract in Byelorussia. There, the detachment, which, by Summer 1943, was about 800 strong (including non-combatants), even set up its own "town".

This so-called "Jerusalem in the Woods" consisted not only of dugouts that served as living accommodation, but also a command HQ, a metalworking shop, a prison, food and arms depots, a flour mill, a bakery, a soap-making facility, a school, two medical posts (for the wounded and for typhus cases), as well as weapon repair and garment sewing workshops. There was even a camp synagogue with a rabbi.

The "Jerusalem in the Woods", hidden deep in the undergrowth, was practically invisible from the air. Even if it had been spotted, the enemy would have had to cross numerous swamps and, in winter, force their way through snow two meters deep to reach it. "We did not fear the woods the way the Germans did. The woods were our freedom and salvation!" Aron declared.

Jewish partisans in the Bielski camp.

Yad VashemDuring the years of the war, the Bielski partisans eliminated around 250 enemy soldiers, blew up 20 bridges and derailed six trains. Zus alone notched up a tally of 47 German soldiers, officers and collaborators. The enemy then put a substantial reward of 100,000 Reichsmarks on the commander's head.

From February 1943, the Bielski fighters were officially incorporated into the Oktyabrsky detachment of the Lenin partisan brigade and were formally subordinated to the Baranovichi central command of the partisan movement. In practice, however, they retained considerable freedom of action.

From time to time, Zus' partisans operated in conjunction with other Soviet partisan detachments. One of these joint operations was an ambush mounted in the village of Vasilevichi.

Group portrait of former Bielski partisans.

United States Holocaust Memorial MuseumThe Jewish fighters entered Vasilevichi masquerading as drunks. They ostentatiously drank alcohol (the bottles contained water) and made a lot of noise, attracting the attention of the inhabitants. Simultaneously, the village was stealthily encircled by several hundred partisans.

As the commanders of the two detachments had hoped, a villager contacted the Germans, located in a neighboring village, to report the presence of the drunken Jews. Several vehicles with German soldiers and collaborators soon arrived in Vasilevichi, only to be eliminated when they came under fire from all directions.

Following the liberation of Western Byelorussia in the Summer of 1944, the roughly 1,000-strong Bielski partisan detachment finally left its hideout and came out of the woods. The majority of the partisans returned to civilian life, but some were mobilized into the Red Army. That included Asael, who was to die fighting on German territory not long before Victory Day.

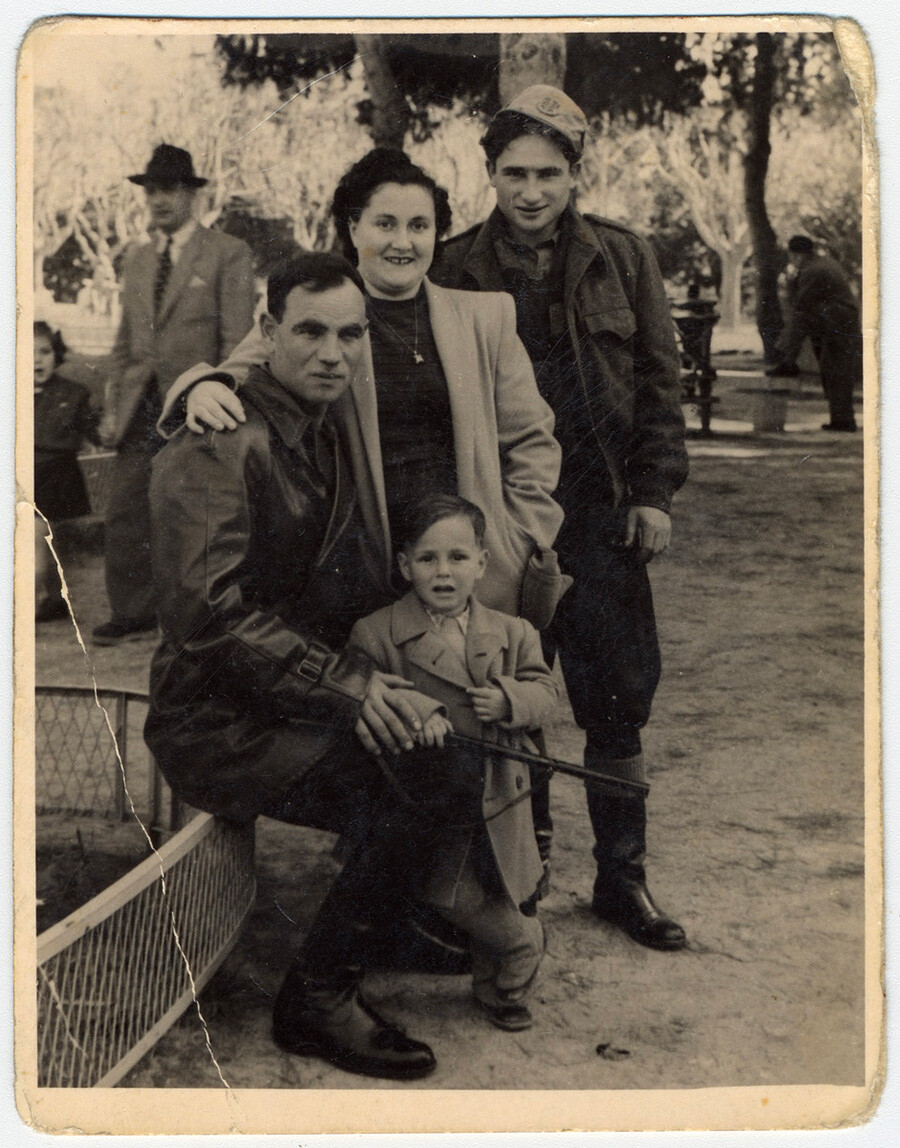

Zus, Sonia, Aaron and Yaakov Bielski pose in the Ramat Gan park, Israel.

United States Holocaust Memorial MuseumShortly after the end of the war, the remaining brothers emigrated to Israel and then to the U.S., where Tuvia got a job as a truck driver, while Zus and Aron went into business.

In total, the Bielskis allegedly saved 1,230 Jews from death. And both those who had been saved and their children always remembered to whom they owed their lives. They remained in regular contact with the brothers and organized periodic testimonial dinners and other celebrations in their honor.

In the USSR, it was taboo to go into details about the activities of Jewish partisan detachments in the war years. No awards were conferred on the brothers, and their exploits only became known after the disintegration of the country.

The world, in turn, got to know the Bielskis in 2008 with the box-office release of Edward Zwick's biopic 'Defiance', which loosely retold the story of the detachment. In it, the role of Tuvia was played by British-American actor Daniel Craig, best known for playing James Bond.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox