In 'War and Peace', Lev Tolstoy describes Napoleon issuing orders, including "one to deliver as soon as possible the counterfeit Russian banknotes prepared in advance for importation into Russia". And this is not the author's invention. The emperor really did use this tactic and not for the first time: Prior to the invasion of the Russian Empire, on his orders, Prussian coins had been minted and British and Austrian banknotes printed.

According to one version of events, a Parisian printing house run by Monsieur Fain, the brother of an aide to Napoleon, began to print counterfeit Russian money shortly before the invasion. The printing plates were executed by an engraver by the name of Lale: In a month, he made 700 of the plates. No-one knew about the operation except for Charles Desmarest, department chief at the Ministry of Police. The work went smoothly: After printing, the forgeries were thrown on a dirty floor and trampled underfoot to make them look like genuine money that had already been in circulation.

According to another account, only part of the forgeries was printed in Paris and then the printing house was moved to Warsaw and Vilna (now Vilnius) to be closer to enemy territory.

Loaded onto 34 wagons, the counterfeit banknotes traveled with the Napoleonic army to Russia. The French planned to use the money to pay for food and lodgings and were prepared to print more forgeries. According to one legend, Moscow's Old Believers greeted Napoleon as a liberator and in gratitude he presented them with a traveling printing press. And, so the story goes, "rubles" began to be printed in the village of Preobrazhenskoye.

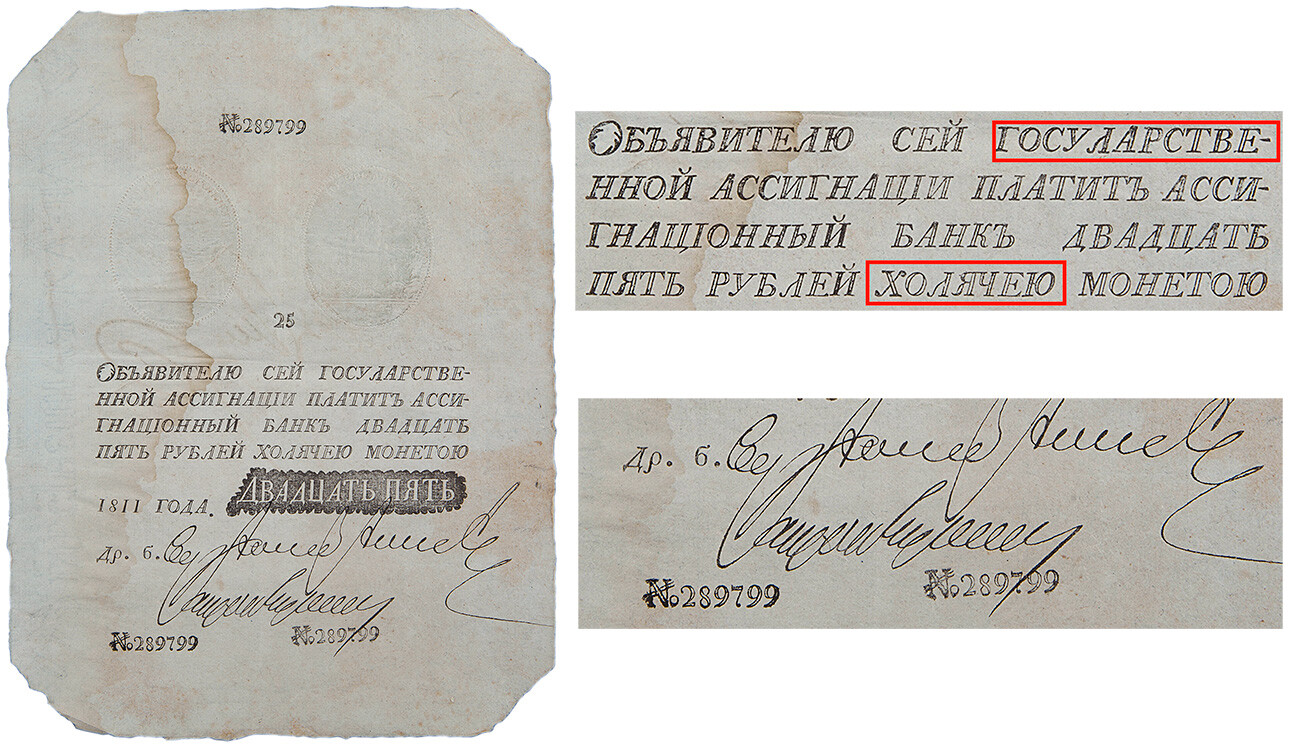

Only the very observant noticed that they had a counterfeit note in front of them. As far as quality was concerned, it was better than the genuine banknotes. Firstly, the paper had an elegant light bluish tinge and, secondly, the notes were made on more up-to-date equipment, so the printing and embossing on the forgeries was discernibly more even and the watermarks weren't bad, either. Even the official's stamp with its barely noticeable flaw line, which was put on the real Russian money, was improved upon and instead of a real signature an engraved one was used.

The counterfeiters were let down by the inscriptions: They did not know Russian, so they failed to spot that some letters had been muddled up. Thus, instead of "Spiridon" it said "Spiridot". And who was going to bother about why the "bearer of the slate currency note" was to be paid on demand "25 rubles in legal lender"?

Most remarkably, officers of the French army were paid with the same counterfeit notes. And they tried to get rid of them as quickly as possible, exchanging them for gold and silver. Aside from that, the French opened money changing counters at the Kamenny Bridge in Moscow where five-ruble bills were valued at one silver ruble.

In fact, even those who agreed to sell fodder to the French demanded payment in coins, not notes. Paper money was excessively vulnerable to financial market fluctuations: In 1797, paper rubles were being exchanged for 75.5 kopecks in silver. Paul I ordered the whole of the existing reserve of paper money to be destroyed and around 5 million rubles ended up on the bonfire. Even the melting down of precious tsarist silverware to make coinage did not help. Inflation in Russia continued to grow and, at the start of the war, the paper ruble was scarcely worth more than 25 kopecks.

It is believed that, during the retreat from Russia, Napoleon ordered the destruction of the counterfeit money that had not yet been put into circulation. But, the forged notes that were already in use remained in circulation after the war. From 1813 to 1817, over 5.5 million rubles' worth of them were found. And the amount that continued to circulate or simply remained in people's hands in Russia is incalculable. In the first year after the war, banks even accepted the forgeries alongside genuine notes. The ‘Napoleonovki’ even ended up in the regimental coffers of Russian troops returning from France: around 300,000 out of 1.5 million rubles turned out to be counterfeit.

The exchange rate of the paper ruble continued to fall: In 1815, it was worth 20 silver kopecks. A rescue plan was proposed by Finance Minister Dmitry Guryev – to exchange the bills and set up a body that would have a monopoly on money printing. And, so it was that a State Printing Office came into being by decree of Alexander I in 1818: It produced paper money for all the territories of the Russian Empire, determined its design, manufactured the paper and printed the bills.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox