How to be funny: Tips from an online cartoonist

Nobody suspected that Russian goalkeeper Igor Akinfeev’s leg would become a national hero and the World Cup’s most memorable meme: “The Leg of God!” as it was baptized after the historic Russia-Spain match. This latter-day miracle sent Russia into the World Cup quarterfinals for the first time since the Commies left power.

But even before one limb became more popular than the rest of the squad put together, 40-year-old cartoonist Kirill

Signed: “Leg of Akinfeev”

Kirill AnastasinSeize the moment

“It's not wholly true that Russia won thanks to Akinfeev, who jumped the wrong way but managed to stick his leg out. There were many other factors, it was a team effort,” says

But he quickly realized (correctly it turned out) that the leg — the final play of the game — would get all the glory. What did he do? Went overboard, and put up a monument to the Leg of God.

Although that could never actually have happened, the wind at the time was blowing in that direction. His drawing even landed on TV. He caught the zeitgeist. And that, according to

“No-no, it’s not spring yet. I just need to use the bathroom”

Kirill Anastasin

“Quentin, let's film Jango in 3D”

Kirill Anastasin“True, if you think about why a particular work is successful, first of

“It’s about me!”

“I’ve always enjoyed making people laugh. At school, I showed my cartoons to classmates and watched their reaction closely. When they laughed, I felt great.”

His first regular character was Doc (a psychotherapist)

![“There are 100,500 ways to overcome autumn depression, but they all start at Sheremetyevo [airport in Moscow]](https://mf.b37mrtl.ru/rbthmedia/images/2018.09/original/5bae188615e9f927260e679b.jpg)

“There are 100,500 ways to overcome autumn depression, but they all start at Sheremetyevo [airport in Moscow]"

Kirill Anastasin

“Are we migratory birds?” “No” “Then let’s take the train”

Kirill Anastasin“It’s about me!” is the secret of winning the audience, believes

Text on the stomach reads: “Deadline.” Santa: “I guess I need to wait my turn.”

Kirill AnastasinIf you’re not sexist, don’t be afraid of accusations of sexism

Cartoons on hot-button issues always risk crossing the line. Even experienced cartoonists do it. An example is

But it’s self-censorship that is the real killer of creativity, he believes. And here, curiously, the artist is helped by faith in his own rightness.

“I don’t do political topics, but sometimes can’t avoid social issues. For example, I had the 'Daddy’s belt' cartoon and others about personal growth

Daddy’s belt. Thousands of well-bred generations. Bloody good discipline.

Kirill AnastasinParadox

In humor, believes

Or Godzilla and a car

“Where did you park the rust bucket?”

Kirill Anastasin- “Comedy Writing Secrets

” by Mel Helitzer — essentially a handbook of humor. Suitable for those wanting a systemic approach. - “Connect Using Humor and Story

” by Ramakrishna Reddy — a digest of comedy techniques. For those wanting to add a touch of humor to work meetings, speechesand presentations. - “The Hidden Tools of Comedy

” by Steve Kaplan — a comprehensive humor guide for those looking to write screenplays.

Simplicity

Good news for those who can’t draw: the trend these days is to keep things simple.

“The modern consumer of humorous content is not overly fussy: he doesn’t care about artistic talent. Look at Internet memes with Trollface, it's primitive. But that’s what the audience wants.”

It applies to ideas, too. The simpler, the better.

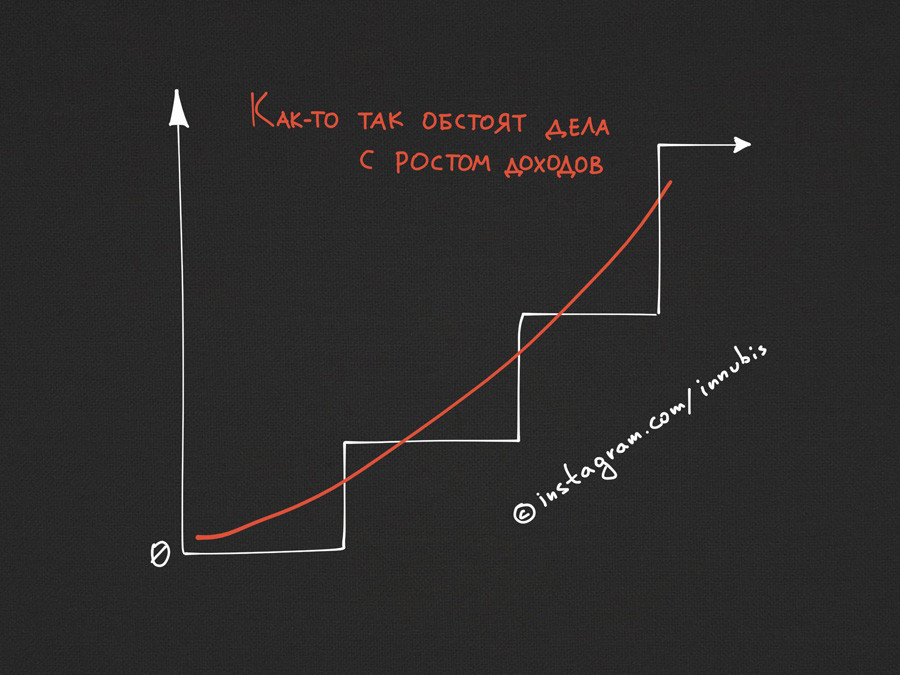

“I had a few unsuccessful efforts in terms of user impact, like this cartoon for smart alecs. Vedomosti’s economics columnist once called it an “IQ CAPTCHA

“This is how things basically stand regarding income growth”

Kirill AnastasinOn Oct. 4-5, Moscow will host the Great Eight creative industries festival, where Kirill

Kirill Anastasin

Vadim FrantsevIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox