Anton Chekhov (in the center) was definitely among those who we can name the Russian intelligentsia.

TASSEverything is complicated about the word ‘intelligentsia’. While it traces its origins to Latin, the word only became famous worldwide thanks to the Russian language. The term refers to all sorts of educated people, but it’s now used to describe those who are messianic and moral high-ground champions. While many praise the intelligentsia as society’s conscience, others despise them for being detached from reality; and yet others, such as Vladimir Lenin, have called them ‘sh*t’. Seriously – what’s all the fuss about?

That's how members of the Russian intelligentsia react to the stupid people around them (scene from Heart of a Dog movie, 1988).

Vladimir Bortko/LenfilmIn Russia, when someone says the word ‘intelligentsia’, one is likely to imagine the following: a good-looking person from the middle class, perhaps with a degree in the humanities, one who speculates about world affairs, politics and, of course, Russia’s future and destiny. In the Middle Ages, however, ‘intelligentsia’ had a completely different meaning.

The Latin word ‘intelligentsia’ could mean ‘understanding’, or ‘ability to understand’, or ‘notion, concept, idea,’ and was used both in the singular and plural. As Saint Thomas Aquinas wrote in the 13th century, “in several works translated from the Arabic, the beings we call angels are regarded as intelligentsias, perhaps because they are good at thinking.” So, intelligentsia were once considered angels, but today, they are predominantly mere mortals.

At first, ‘intelligentsia’ meant the ability to think and reason, but in the 19th century, after borrowing the word from German, Russians started to apply it to those who had such an ability, meaning educated people. It’s difficult to identify the exact moment when the term changed meanings, but historians believe Vasily Zhukovsky, the foremost Russian poet of the early 19th century, was the first to use the new meaning, or, at least, he was the first to do it in writing.

Portrait of Vasily Zhukovsky, who was the first to use the term intelligentsia in its contemporary meaning.

Karl Bryullov/Tretyakov Gallery“Our finest St. Petersburg nobility [is] the intelligentsia with European education and way of thinking,” comments sociologist Lev Gudkov, citing Zhukovsky’s diary. “So, he unites three components in this word: a pro-European orientation, a fine education, and a desire to enlighten the people.”

That's how typical intelligentsia of Russian empire looked:" 'Sreda' ('Wednesday'), Russian literary group of the 1890s.

Getty ImagesPetr Boborykin, a Russian journalist and writer who is widely believed to have popularized the term ‘intelligentsia’, enlisted vital features of this social stratum in his novel, Dependable Virtues. A member of the intelligentsia prefers ethical perfection to worldly possessions, thinks about the future and progress, and constantly improves oneself. “At the end of the novel, Boborykin hints that Russia and its people are a new religion for the intelligentsia,” says historian Sergey Motin.

Ever since, the context has remained the same: the Russian intelligentsia is about high ethical standards and moral superiority, not just about having a fine education and being an intellectual worker. “There are intellectuals in the West, but only we have the intelligentsia,” wrote Komsomolskaya Pravda in an article defining the term.

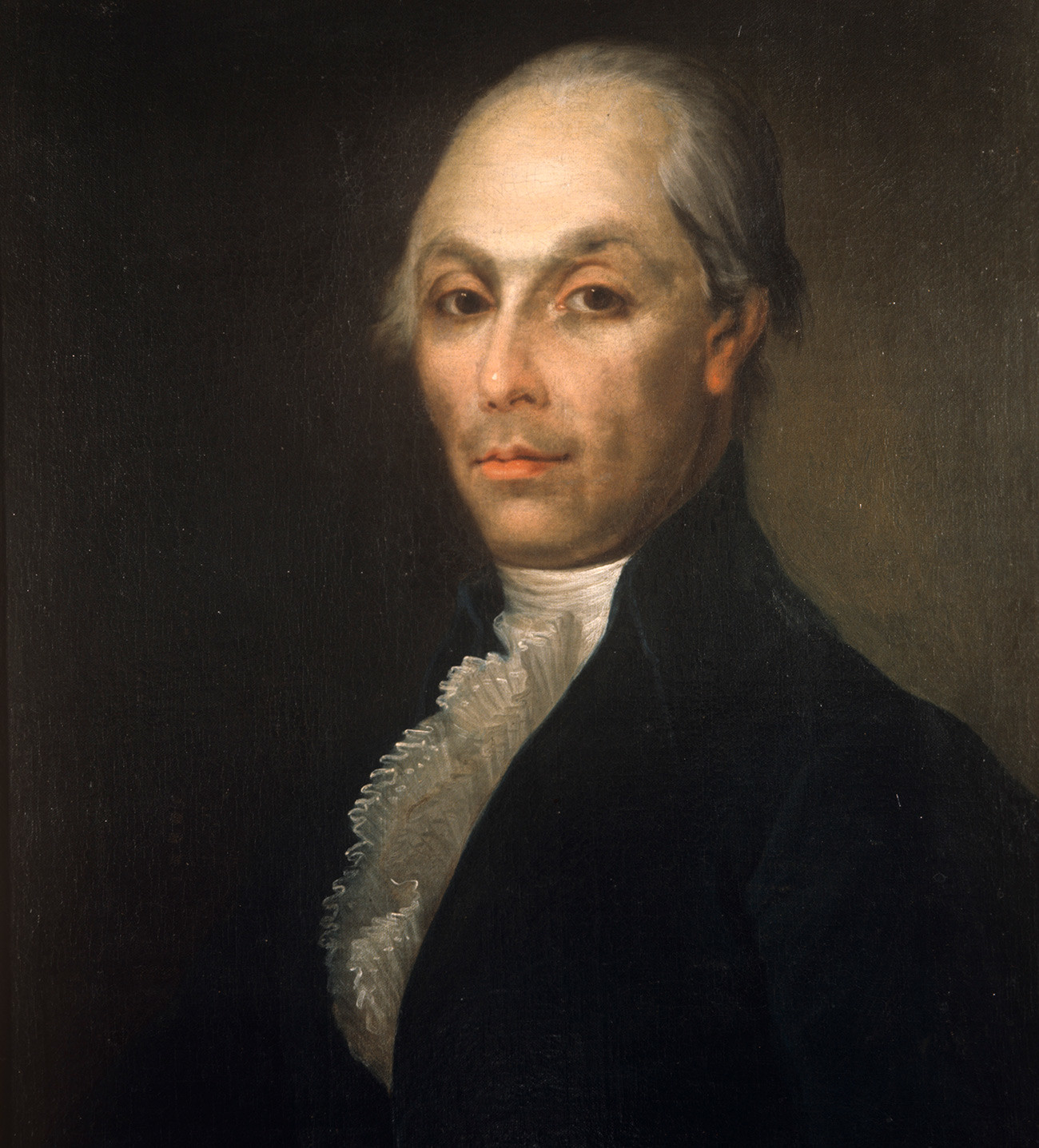

Portrait of Alexander Radishchev, who definitely was a member of the Russian intelligentsia.

V. Shiyanovskiy/SputnikCoined originally to describe freethinkers, both the intellectual and moral elite, the term ‘intelligentsia’ in the Russian Empire was deeply associated with the pro-Western and liberal part of educated society, which was often opposed to the tsars and the government. For instance, Alexander Radishchev, an author and social critic who wrote A Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow, criticized the political and social system under the rule of Catherine the Great, later punished with exile for it. He was a classic member of intelligentsia circles.

It comes as no surprise that many pro-government Russians, including patriotic intellectuals, labeled the intelligentsia (usually put in quotes to diminish respect) as Russophobes, or just pointless whiners.

“There are people who love to call themselves ‘intelligentsia’… who don’t enjoy a strong mind or healthy logic… These ‘intelligentsia’ members try to proclaim their emancipation and independence by scolding Russia,” Ivan Aksakov, a patriotic intellectual, claimed in 1868.

With their pro-European values, the Russian intelligentsia was something very close to those who are today ironically called ‘snowflakes,’ or ‘bleeding-heart liberals’. Looked upon with suspicion under the tsars, they also didn’t have much success under the Soviet regime.

Lenin, for instance, was annoyed by those members of the intelligentsia who remained “lackeys of capital” (as they didn’t support his revolution). Infuriated, he wrote in a letter to Maxim Gorky: “They think they are the brains of the nation. In fact, they are not the brains, but sh*t.” Nevertheless, it doesn’t mean he hated all of the intelligentsia – the leftists were always welcome.

As time passed, more and more people began to use the term ‘intelligentsia’ with ironic connotations, portraying them as people who are too busy thinking about moral problems to actually do something practical and useful. “He never worked anywhere. Working would interfere with his thinking about the Russian intelligentsia’s mission… and he considered himself part of it,” Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov mocked this stratum in their satirical novel, The Little Golden Calf.

At the same time, some people considered part of the intelligentsia influenced society and tried to improve the world – for example, Soviet physicist Andrei Sakharov, who championed human rights in the USSR, and suffered state oppression. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975.

Andrei Sakharov, a humanist, an intellectual and certainly a member of the Russian intelligentsia.

Valentin Sobolev/TASSNowadays, there is a more common term that has nothing to do with politics or the social role of the intelligentsia – intelligentny is an adjective meaning “polite, educated and well-behaved”. This term may apply to any person who you respect, and consider his behavior a role model for anyone in society. But intelligentny people never call themselves that. Perhaps that’s why it’s so hard to define who the Russian intelligentsia are today.

This article is part of the "Why Russia…?" series in which Russia Beyond answers popular questions about our country.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox