Who are the Ainu and why do authorities still deny their existence?

Two women in traditional costumes stand opposite each other. One holds a dark eye makeup pencil, with which she is trying to draw something that looks like the famous "Joker smile" from the Batman comics on her face.

"Asya, do it like this…," says one young woman to the other in Russian, using her fingers to show how it's done - from one cheek to the other. The other does as she is instructed. The black pencil leaves charcoal-like marks on the woman’s cheeks and above her mouth.

"Wow, a real Ainu!" says the first woman with satisfaction.

They have come to the Japanese Island of Hokkaido, which has several Ainu reservations. They are a very ancient people who once inhabited an enormous territory on the shores of the Pacific, including present-day Japan, Sakhalin Island, the Kuril Islands and the southern Kamchatka Peninsula.

According to official data, only 25,000 have survived in Japan and just several dozen in Russia.

In Russia, little is known about the Ainu. What is known can be enumerated on the fingers of one’s hand: The Ainu used to live in the Far East; the Ainu have been persecuted by someone throughout their long history; and, finally, the Ainu have disappeared as an ethnic group in Russia - they were deleted from the official register of ethnic groups in 1979. That is all that is commonly known about them.

Still, there are Ainu in Russia. These two women, filmed by a Russian ethnographer from the Far East, look with curiosity at the huts in a reservation, something that Russia doesn't have, while shyly telling a Hokkaido Ainu that they know how to make the fold in their costume correctly. They don't need to be taught to do it.

Smiling women and very hairy men

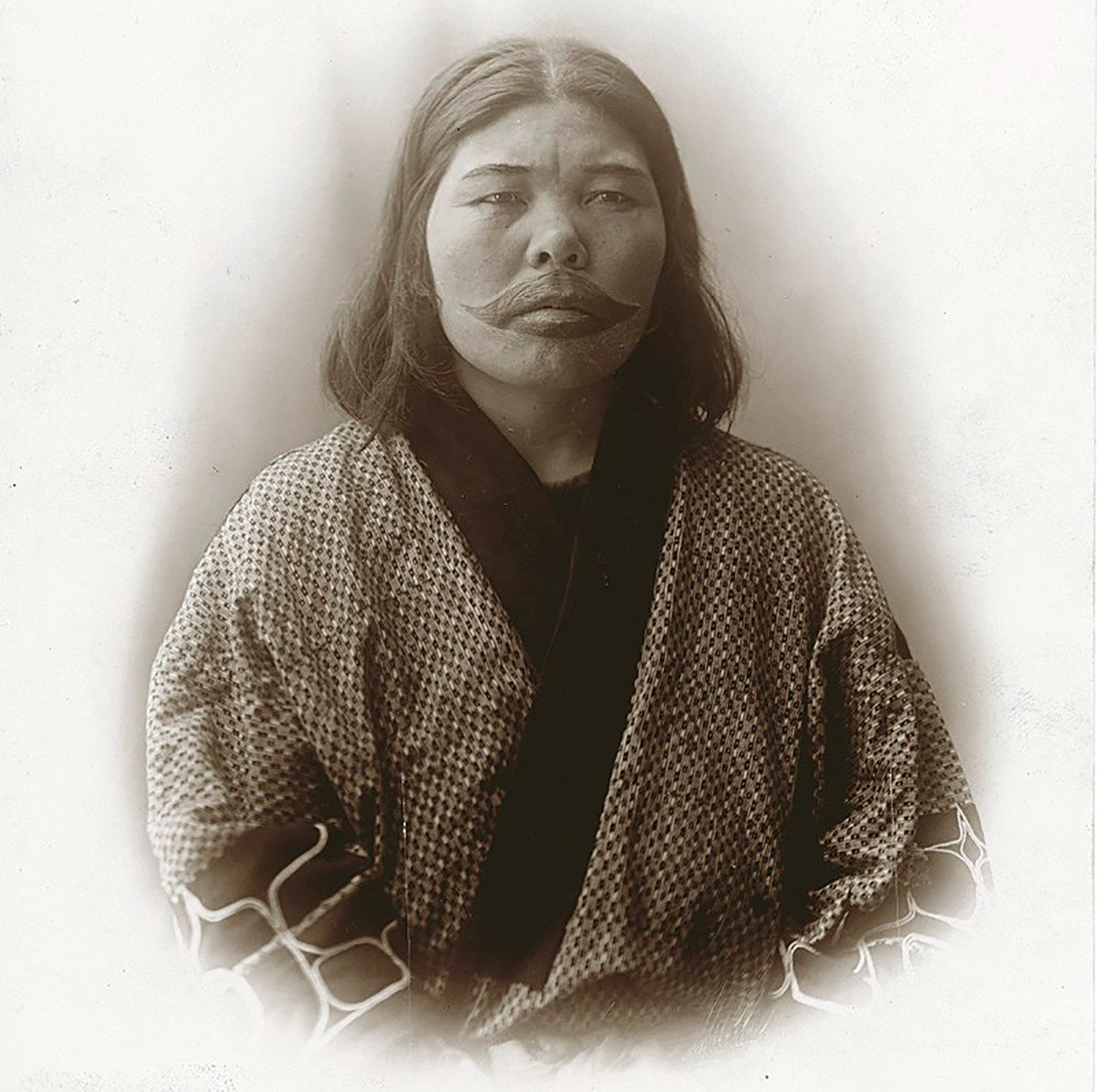

The "Joker smile" is a lip tattoo, a distinctive feature of Ainu women. In the past, they would start having it "scarified" from the age of seven: Using a ceremonial knife, cuts were made in the corners of the lips, and charcoal was rubbed into the cuts. Every year several new lines would be added and the "smile" would be completed by the bridegroom at the wedding. Women also often had arm tattoos, as well.

Nowadays, they no longer do it this way. Now, they only use a pencil to draw the “smile” and only on big occasions. The last Ainu woman tattooed in accordance with all the rules died in Japan in 1998.

Ainu Woman

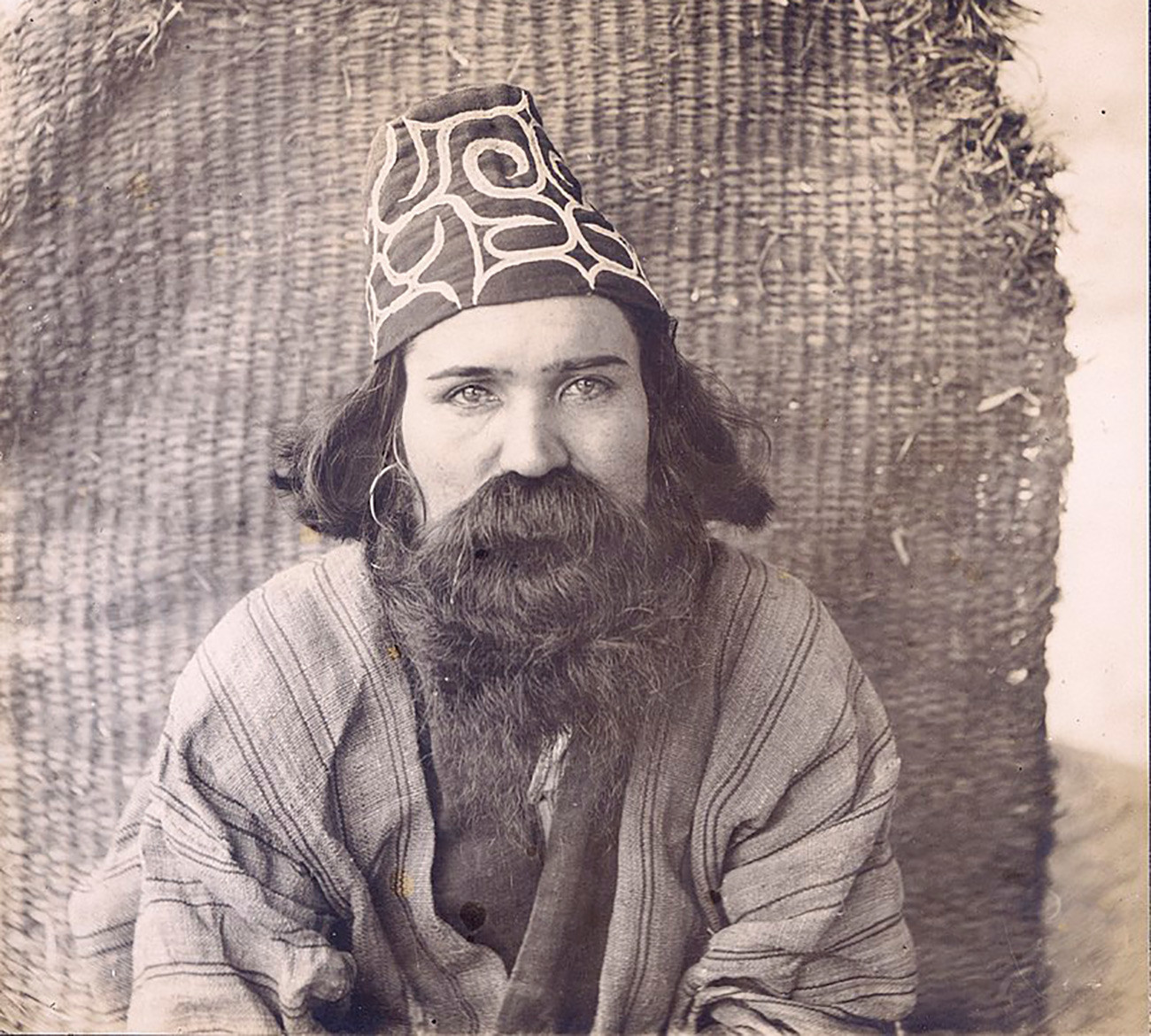

Missouri History MuseumMen, on the other hand, were distinguished by an abundance of facial hair. For example, they had special sticks to support their long moustaches at mealtimes. As early as the second century BC, an ancient Chinese treatise mentioned the existence of the "hairy" people. The 18th-century Russian explorer of Kamchatka, Stepan Krasheninnikov, called the Ainu "woolly Kuril people", all because of their men.

There is another curious detail: Initially, the Ainu looked more like Europeans than Asians. Krasheninnikov himself and other early Russian explorers described them as similar to Russian peasants with dark skin or to Gypsies, but not at all like the Japanese, Chinese or Mongols. The reasons must be sought in the origin of the Ainu. But in their case, one mystery gives rise to another: No-one knows where they came from.

The unknown race

The Ainu are believed to go back 15,000 years - further back than the Sumerians or Egyptians. For this reason, some people say the Ainu are not just a people, but a whole "Ainu race".

Ainu leader

Missouri History MuseumThere are two theories about their origin. The first is the "northern theory" - namely, that they came from the land in the north, later settled by the Mongols and Chinese. The second is that their ancestors are from Polynesia, because the Ainu have many similarities in dress, rituals, religion and tattoos to the inhabitants of Oceania.

What is known for sure is that the Ainu were the first native people on the Islands of Japan, although the Japanese themselves have never liked this fact and have tried to hide it. The Japanese had a long-standing feud with the Ainu over territory. The natives predictably lost one battle after another, because they had never had either statehood or an army, and were pushed ever further north from the islands. Even so, back in the Middle Ages, it is believed half of Japan was inhabited by the Ainu.

"The tragedy of my people is comparable only perhaps to the tragedy of the indigeneous people of North America, the Native Americans," says Alexei Nakamura, head of the Kamchatka Ainu community. However, it is not just Japan that banished the Ainu.

Erased from history

In the Russian Empire they were not allowed to call themselves the ‘Ainu’ people, because the Japanese claimed that all the lands inhabited by them were part of Japan. For their part, the Ainu lived both on islands claimed by Japan and on the islands in Russia's possession.

Married Aino couple

National Museum of DenmarkAt some point, it became shameful and simply dangerous to call oneself an Ainu - many of them assimilated, learned Russian and became Orthodox Christians. Admittedly, the Communists actually saw the Ainu as Japanese - as a result of certain ‘interbreeding’, the Ainu had acquired more Asian features. "And so it happened that in Russia we are Japanese and in Japan we are Russians," says Alexei Nakamura, who has a Russian first name and Japanese surname.

Ainu child

Missouri History MuseumHistorically, the Ainu had no surnames - they were given them either by the Russians or Japanese, and some later adopted Slavic surnames. Many did so during the time of the Stalin-era political repressions: The NKVD [precursor of the KGB] state security organs denied them Soviet citizenship, and because of their connection with the Japanese, they were accused en masse of espionage, sabotage and collaboration with militarist Japan, and sent to prison camps.

"After World War II, it was unacceptable to mention the Ainu anywhere. There was a secret order by Glavlit, the censorship watchdog, which was called precisely that - On the Prohibition of All Mention of the Ainu Ethnic Group in the USSR," recalls Alexander Kostanov, a doctor of historical sciences. After Japan had capitulated, the question arose in 1946 of repatriating the Japanese population from Russian territory. "The Ainu were not regarded as former subjects of the [Russian] Empire. They were regarded as subjects of Japan," says Kostanov. That's how almost all of the Ainu ended up on Hokkaido.

The present

In 2010, during the latest all-Russian census, 109 people described themselves as Ainu. But, at the insistence of the government of the Kamchatka Territory, they were not registered as Ainu. Five years later, the Ainu registered themselves as a non-commercial organization, but it was disbanded by a court decision. The reason? Officially, because “no Ainu exist”.

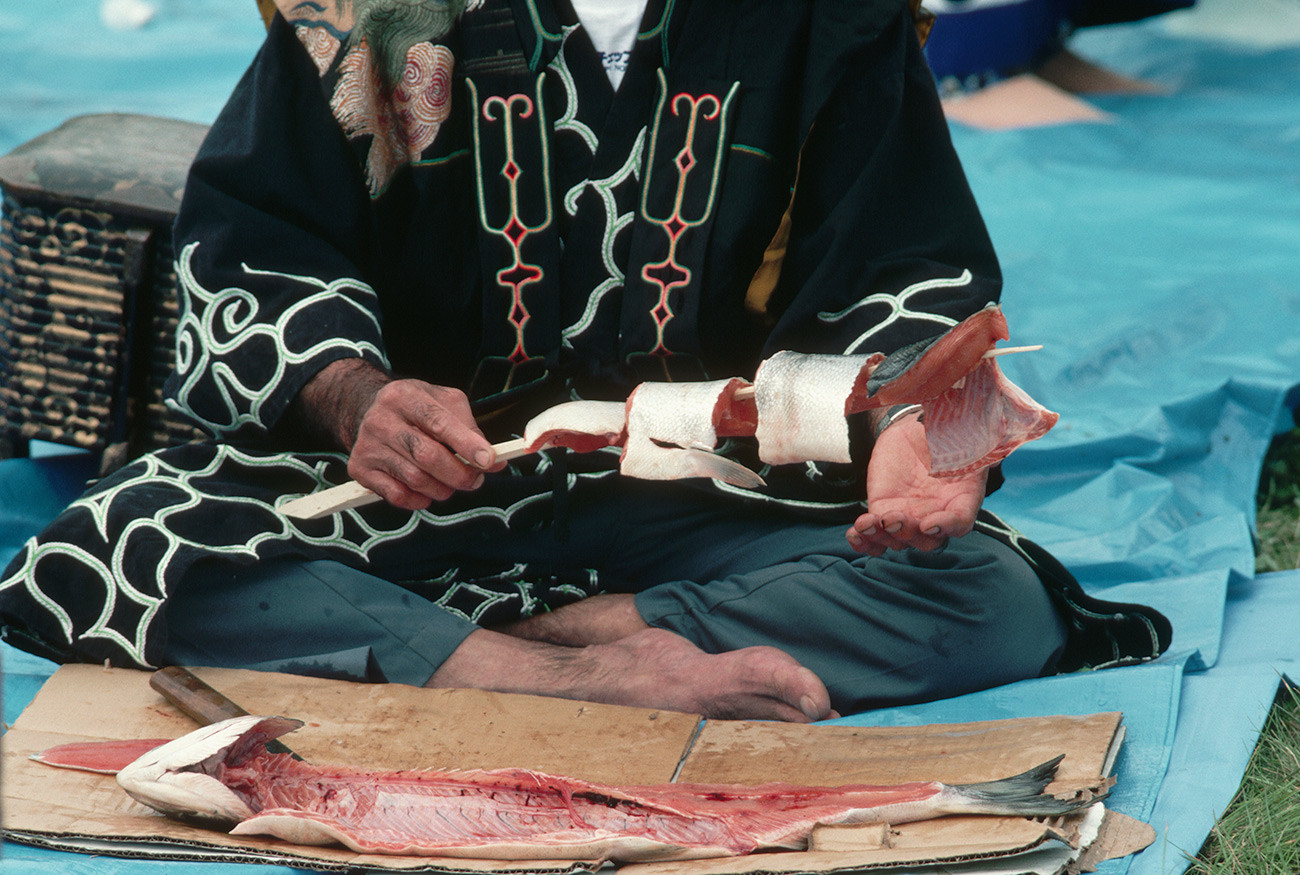

"This means that we do not have the right to go fishing or hunting like other small ethnic groups. If we go out to sea in a small boat, we are poachers. And the fine for that is huge," says Nakamura.

Hokkaido has the Utari association, a network of Ainu educational and cultural centers with 55 branches. In Russia, the Ainu have nothing. All the textbooks are in English or Japanese and brought from abroad. "We have tried to cooperate with Russian authorities, but then are forced to give up. The question of the Kuril islands always comes up; they want us to become politicized and express a view on the issue," he explains.

But the Ainu are not keen to be politicized. It seems they are not keen to talk much about their identity, either. According to the statistical report, "The Japanese diasporas abroad", 2,134 Japanese live in Russia. They include some people of Ainu ancestry, but they identify themselves as Japanese, because it entitles them to visa-free travel to Japan. There are so few Ainu who need recognition that they are remembered only by ethnographers. Sadly, Nakamura says that it is probably his last interview: "Because nobody wants us."

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox