How face control works in Moscow night clubs

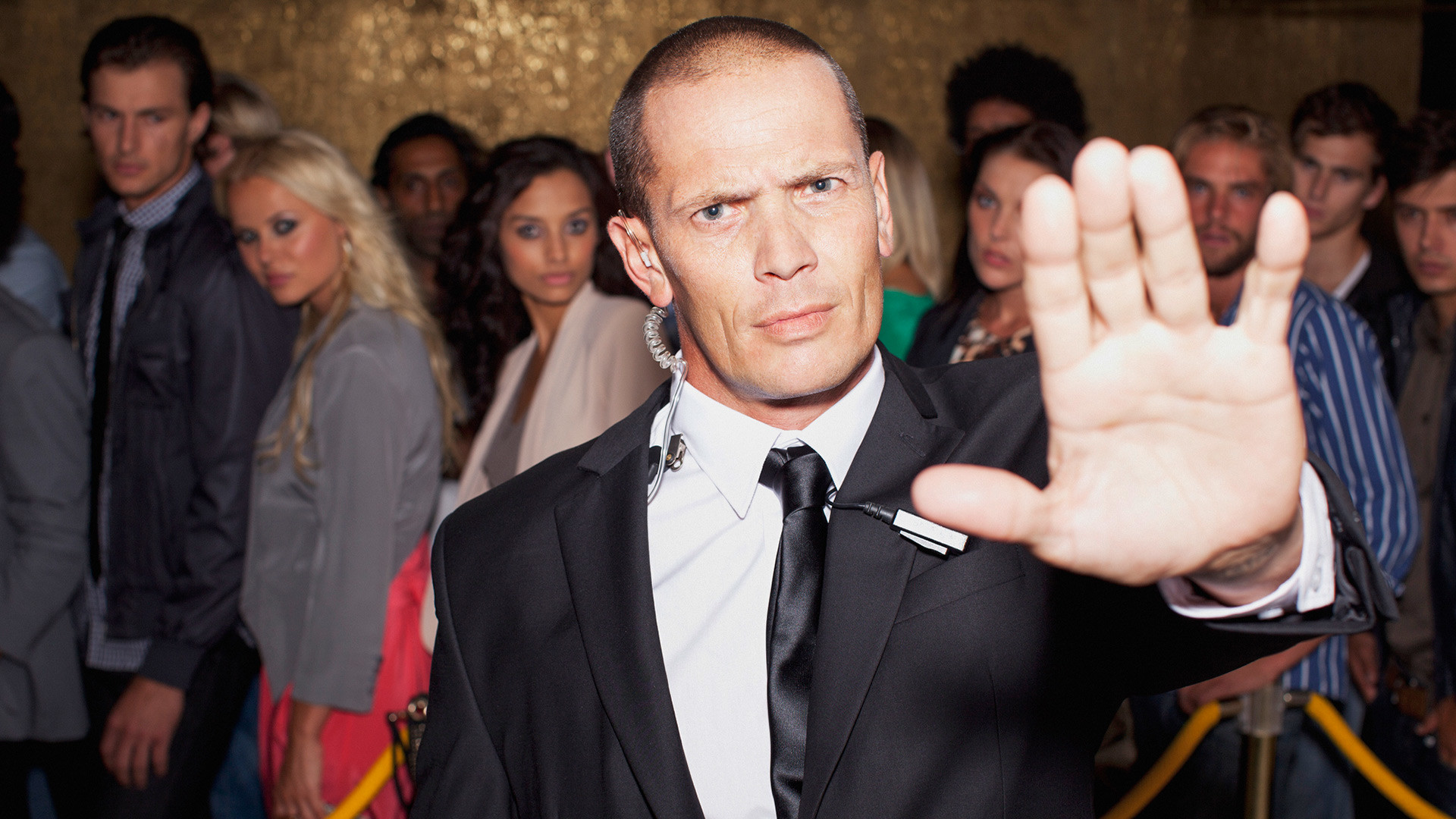

“F*ck you, stop munching anabolics,” says a large man in a black jacket, standing behind a metal fence.

“Yeah, I guzzle everything, a-hole. I got a big appetite,” his colleague answers. They both guffaw loudly. They are the face controllers at ICON, one of the most famous clubs in Moscow.

Two blondes loiter by the entrance. Both are wearing leather leggings and heels, one violently blows bubble gum. They don’t dare approach face control, as if waiting for something. My friend and I also hang back, but our reason is to gather material for this article.

“Ladies, you going inside?” a guy of about 25 addresses us with a pleasant smile. He is dressed in a smart suit and coat.

“Yeah, why d’you ask?”

“Entrance is 3,500 rubles [$55], tables start from 30,000 rubles [$471]. Plus face control will be tough,” he says, examining our puffa jackets and flat shoes. He hands us a business card marked “Promoter.”

“Go and try, then come back,” he says and heads toward the blondes.

Gradually, more and more people arrive, until a crowd of around 20 is congregated by the entrance, but it does not smell of glamor. At some point a large group of men from the Caucasus and girls with lips puffier than our jackets turn up. After a few minutes, a member of security invites them into the VIP zone.

It’s impossible to know what the face control rules are. A young guy in a presentable woolen coat and a fresh-from-the-barber haircut is sent away without explanation. A minute later, a corpulent man of short stature is allowed in, followed by two women in sneakers and wide silver-colored pants. Foreign speech can be heard from the direction of the VIP entrance — sounds like Italian.

Girls in the Moscow night club "First"

Sergey Guneev/SputnikIn the end, we too get turned away. The guy at the entrance advises us to pre-book a table next time, or get VIP cards.

“Well, what did I tell you? Let me help you,” says the promoter, hoping to sell entrance tickets. After we decline, he again pesters the blondes.

“Nah, we’re gonna meet someone here and then go in,” replies one of the girls. The other takes out a cigarette with a shaking hand and lights it nervously. They’ve been here for 40 minutes already. As for us, we’re leaving.

Pasha Face Control and the no-entry club

Today, the word “glamor” is hardly applicable to Moscow club-goers. Yet only about a decade ago, entry into some hallowed venue with uber-strict face control was a major achievement worthy of cult status among metropolitan mods. Clothes and makeup had to be done accordingly.

“Well, I’m dressed sexy enough, ain’t I? Gonna let me in?” the female lead asks face control in the Russian TV show Club, which was all the rage back in the 2000s.

“You tried, only you forgot about make-up! Where’s your manicure? You’re not dolled-up enough, go do it!” responds face control, barely restraining a smirk.

The club from the series was a parody of Shambala, which opened in Moscow in 2001 (since closed down). It was promoted and owned by Alexei Gorobiy, and represented the epitome of Moscow glamor — beautiful women and wealthy “daddies” lined up for sets by foreign DJs and expensive tables on the huge summer terrace.

Diaghilev, another of Gorobiy’s clubs, was even more popular. Its distinguishing feature was the theater-style boxes on the upper floors that sold for tens of thousands of dollars, plus expensive toilets, and crowds of women and celebrities at the entrance.

The symbol of the club was Pasha Face Control (real surname Pichugin), who had previously worked with Gorobiy. According to Pasha himself, he let in businessmen who arrived in expensive cars, and women and transvestites who made their own clothes. One New Year’s Eve he sold a table in the club for 40,000 euros. At the same time, Pichugin could turn away a famous singer or politician without an explanation. The image of the merciless face controller was so etched into the mind of Russian show business that Russia’s DJ Smash made a video about him, making Pasha famous throughout the country.

Diaghilev itself burned down in 2008. Gorobiy opened several more clubs, before dying of a heart attack in 2014 in Bolivia. Then on Nov. 10, 2019, Pasha Face Control also died, aged just 38. The cause of death remains unclear.

New face control rules

“Today, ICON usually lets in women in short skirts and high heels, and potbellied men, often foreigners, looking for a girl for the night. There used to be a feeling of exclusivity at the club entrance, but now any old slimeball gets through,” complains Diana, a model who used to work at club events.

Her fellow model friend Maria agrees that the era of tough face control in Russia is long gone.

“To get into a club, you need to be neatly dressed, an adult, and not drunk. And even if some goon doesn’t let you in, there are always other places,” she says.

According to her, the situation at Gipsy, another well-known club, is completely different, and face control is focused on “active youth in trendy gear.”

There are no queues at the entrance to Gipsy. Face control, consisting of two bouncers, tries to explain to a group of Chinese that they can get into the club if they buy tickets to a concert by rapper LSP, who’s performing there today. From the upper floors a chaotic beat is heard against the backdrop of frenzied screams from female fans. The Chinese clubbers place several banknotes into the doormen’s hands and enter without any problems. We too are invited to buy a ticket and go inside.

Alternatives to trendy clubs

Those who for some reason are not allowed into Gipsy have other more authentic options. Face control at Rock-n-Roll Bar&Cafe, for instance, popular with young people, is just a guy and a slender girl in a black T-shirt. From the street you can hear “Personal Jesus” by Depeche Mode playing inside.

A girl in an austere coat tries to persuade the face controllers to let her in with two friends. The reasons for the refusal are quite prosaic — a stocking has slipped down the leg of one of the ladies, who can hardly stand up straight. The third girl pulls the stocking up, trying to impart a more presentable appearance to her tipsy friend.

“Girls, I’d let you in, but your friend needs to go home to bed. No entry if drunk, I’m afraid,” the face-control girl says sympathetically.

“Who gets drunk that quickly? Come on, you alky, let’s go,” one of the girls says irritably. Together they pick up their woozy friend and head towards the subway.

Half-an-hour’s walk away is another club — Mayak, one of the oldest in Moscow. Opened back in 1993 on the site of the buffet bar of Mayakovsky Theater, it was positioned as a hangout for musicians, actors, artists, and journalists.

Even from the entrance a girl can be seen staggering slightly and singing a jazzy tune. Some people have already fallen asleep at the tables, and a short young guy in a black turtleneck is trying to grope a tall woman. Everything around smacks of a cheap wedding.

Face control consists of two bouncers.

“The main thing for us is that people aren’t too drunk. Otherwise we basically let everyone in. Just show your passport,” says one of them.

At this moment a middle-aged waitress comes running out.

“Sasha, they’ve puked again, stop letting in any old sh*theads!” she shouts.

“Ooh, this place is just right. Sod ICON, it’s for posers,” says a friend. We go inside.

A few days later that same promoter from ICON writes to me.

“Drop me a line whenever you fancy swinging by. I’ll get you some tables and promo codes for free drinks,” he says.

“What about face control?”

“We’ll come to an arrangement with face control, the joint’s got to make a profit,” he replies.

Russia Beyond sent requests for information to all the clubs mentioned in the text. At the time of publication, none had replied.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox