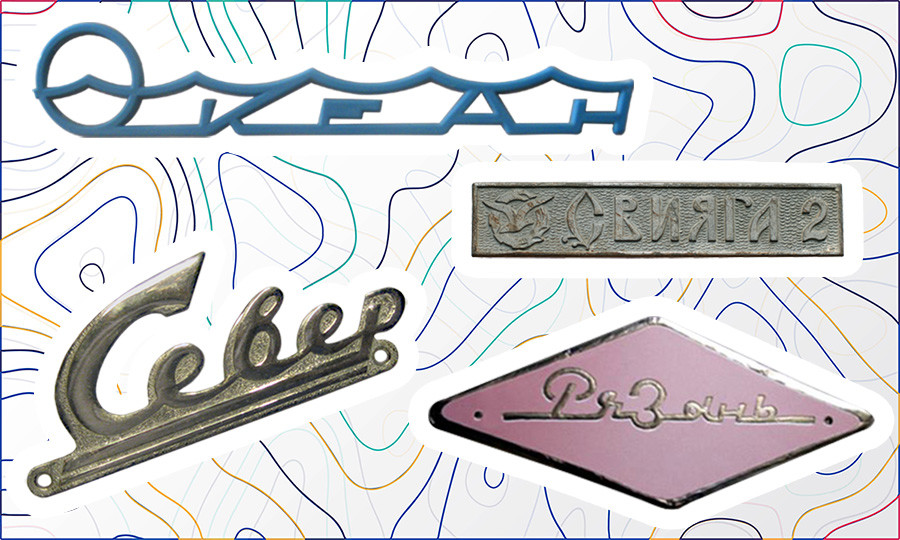

How Soviet FRIDGE LOGOS mirrored history (PHOTOS)

Aleksandr Vasin is a Moscow-based designer with one of the most unusual item collections in the world. He collects old Soviet fridge logos and he’s got a whole virtual museum where you can learn about each one.

When asked why the fridge, he responded: “The refrigerator is a sacred object for every Soviet family. As soon as you got a family, the first thing you bought wasn’t a bed - it was a fridge. Or you’d get them in dorms, where everyone had their own shelf. In any case, it was a shrine in its own right. But what we often remember is the writing on the outside. ‘ЗИЛ’, ‘Минск’, ‘Днепр’ and so on,” Vasin says.

Alexander Vasin

Personal archiveHe began collecting logos back in 2010, when riding bikes with his wife on a dacha where you often come across old, non-working fridges at garbage dumps that people disposed of. “One day, we just couldn’t pass one by without removing the logo.”

The collection grew as the family rummaged through local dumps, as well as abandoned residential buildings and sometimes the online ‘Avito’ buying and selling website. It turned out that a large portion of the fridges came from across the Soviet Union. Although they didn’t differ much in their looks, the logo for each brand really stood out.

Only their creators didn’t have names. “You know what they say. The Soviet Union had no sex, no freedom and no rock’n’roll - but there also was no concept of design. Or rather, it existed underground, or did not carry names. We don’t know the names of the people behind the logos, although they can be seen by millions and became part of every household.”

Vasin never fell in love with another type of appliance as much as he has with the fridge, which is like a focal point of Soviet culture, in his opinion: people would attach things to its door with magnets, like electrical bills, postcards or telegrams - both pleasant and unpleasant. “But that’s not all. When we began collecting them, we understood that logos - their design and technical execution - are often reactions to the changing of the epoch,” Vasin says.

For instance, at first they had these beautiful, large, brutal, metal logos like the ‘ZIS’ fridges, which was concurrent with Stalinist architecture and a demand for brutalism in everything.

Then they had plastic logos, which came amid the fight against architectural excesses, spearheaded by Nikita Khruschev.

“And then, they all became boring plastic rectangles and that was, on the one hand, a transition to a modernist design paradigm and, on the other - a sign of the downfall of the ‘Sovok’ and the culture of graphics,” Vasin explains.

Meanwhile, such a trend wasn’t only witnessed in the USSR. In 2013, Vasin found another logo collection - owned by Richard Protzman from the Netherlands. They managed to set up a joint exhibit in Moscow, both still remaining among the only well-known collectors of fridge logos in the world.

“There’s a story that comes with every logo. The most unusual for me is the ‘Kavkaz’. One of them was found in a sorry state in the middle of an abandoned helicopter airfield near Bunkovo, outside Moscow. The steel logo was the only thing that survived the passage of time.”

Vasin found a similar fridge on the shore of the Oka river in a village vegetable patch. But the owners refused to let the museum’s “researchers” inspect it. “We decided to approach it with screwdrivers, but the owners shooed us away. Funny, considering that the fight for the Caucasus has always been one fraught with difficulty and danger for Russia,” he laughs.

“By the way, here’s an interesting fact. If the fridge was a ‘Kavkaz’, it’s very likely that it didn’t exist in the Caucasus itself and was probably only sold in Khabarovsk Region. While ‘Sever’ (‘north’) could easily have been sold in the south, somewhere in Krasnodar Region.”

Vasin believes this curious phenomenon stems from how the Soviet planned economy was set up: “In order for the transport system to function properly, it had to always be kept going. People would always be transported somewhere in the USSR. For example, a quarter of all prison inmates were always on the move in shifts. It’s possible that the same system was at play with production - something was manufactured in one place, then taken someplace else, at the other end of the country.”

Vasin counts some 100 unique logos among his collection - that’s almost almost the entire Soviet lineup. “Today, we keep our collection in a shoe box at home. Some may think that looking for these badges in garbage dumps is a dirty, unsanitary business. While others are filled with a sense of nostalgia just looking at them. I probably belong to the latter category.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox