Few people in the USSR had the opportunity to listen to Western music on original gramophone records. Such records were a big rarity in the country, they cost a fortune and, as the Iron Curtain descended, it was more and more difficult to get hold of them. Almost all the music associated with the West - rock ‘n’ roll, jazz, boogie-woogie - was unofficially banned (as it “compromised those who listened to it”) and selling records by private individuals was a criminal offense (from October 1931, all private trade had been banned in the USSR; later, a new article - ‘Speculation’ - appeared in the Criminal Code carrying a sentence of up to seven years in prison).

It was then that a unique music medium appeared in the country - homemade records made using x-ray film. They were called ‘bone records’, ‘ribcage records’ or simply ‘ribcages’.

St. Louis Blues William Handy

Igor Bely (bujhm)The spread of the ‘ribcages’ reached its peak in the 1940s-1950s, when the Soviet music recording industry was taken fully under the control of state censorship. Songs by the “people’s artists of the USSR” could be found on ordinary gramophone records, but any other music that was not approved of by the state was considered unofficial and had no chance of being recorded legally.

Thus, for example, in addition to Frank Sinatra, The Beatles, Chuck Berry or Elvis Presley, the ‘ribcage’ record discs were used to record songs by Russian émigrés declared “enemies of the people” in their homeland; or singers accused of anti-Soviet crimes (for example, Pyotr Leshchenko and Konstantin Sokolsky were banned following accusations of treason, as was Vadim Kozin on charges of homosexuality, for which he was sent to the Gulag). Songs of the criminal underworld, which had extremely wide popular appeal, also had no way of being officially recorded.

Therefore, just as the USSR had clandestinely published literature - samizdat (literally “self-publishing”) - there was also a black market in self-recorded music. Big cities, above all Moscow and Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), had a whole industry set up to produce and sell “bone music”.

These were indeed perfectly ordinary x-rays of regular people: They showed joints, spinal columns and ribcages - the latter were the most common because regular fluorography check up was mandatory for everyone in the USSR. X-ray films were cheap and easily available. City outpatient clinics would give away whole piles of x-rays or sell them for a nominal fee: At least once a year, they would have to get rid of this material, which was a fire hazard. But, the pliable x-ray films were an ideal medium for recording music.

Delicado by Brazilian composer Valdir Azevedo

Igor Bely (bujhm)Soviet music fans are believed to owe the appearance of “bone music” to Leningrad resident Ruslan Bogoslovsky, who invented a homemade sound recording apparatus and founded the ‘Zolotaya Sobaka’ (‘The Golden Dog’) underground studio.

“Carefully studying the principle of the operation of the apparatus and carrying out a number of essential production tests at the studio of [Stanislav] Filon (founder of the ‘Zvukozapis Studio’, from whom Bogoslovsky borrowed the idea of making recordings on semi-soft discs), Ruslan made some engineering drawings and then found a versatile lathe turner, who undertook to manufacture the necessary components. In the Summer of 1947, the magnificent mechanical sound recording apparatus was ready,” one of the makers of these types of records, Boris Taygin, wrote in an article for ‘Pchela’ [‘The Bee’] magazine.

The equipment was not unlike a gramophone, but it worked the other way round. Instead of a needle reading the music on the disc, it had a sound recording head. The music made it vibrate and incised the x-ray film. This kind of homemade disc sounded much worse than a vinyl record. It crackled and this crackle was almost as loud as the music itself. But the quality was sufficient to be able to make out the song.

The fact that the ‘ribcage’ records were of flexible material made them significantly easier to sell. The seller (who was known as a ‘fartsovshchik’, the Soviet-era term for a black marketeer) could have a bundle of up to 20-25 records hidden in one of their sleeves.

"Ivan Vasilievich Changes the Profession". 1973

Leonid Gaidai/Mosfilm, 1973As a rule, the traders operated in pairs: One of them negotiated with the buyer, while the second one stood nearby with the goods. Such a record could be sold for between 1 ruble and 1.50 rubles. For students, who were the black marketeers’ main audience, this was a not insubstantial amount. “In my student days, I could live very well for a whole day on one ruble. This amount would pay for breakfast, lunch and dinner,” recalled Soviet music expert and collector Naum Shafer.

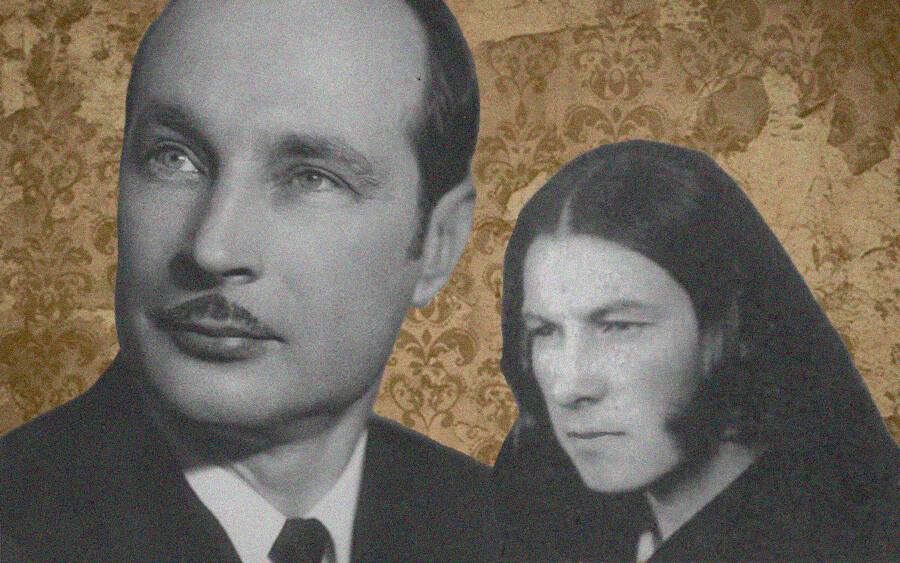

Ruslan Bogoslovsky and Boris Taigin

Archive photoThe traders would also make a lot of money out of them, but they were risking their freedom each time. In the USSR, the sale of goods by private individuals and any form of private entrepreneurship were prohibited. The main producers of the ‘ribcage’ records in Leningrad, Ruslan Bogoslovsky and Boris Taygin, were repeatedly arrested, even though this did not eradicate the illicit recordings.

On the first occasion, Bogoslovsky was sentenced to three years and Taygin to five. Once they got out, however, they set up their equipment again and immediately resumed their former activity. Four years later, Bogoslovky was arrested again and given another sentence of three years. In that time, he had thought up a method of recording hard discs on do-it-yourself equipment and, on being freed, he set up their production - for which he found himself in prison for a third time.

What really sounded the death knell for homemade Soviet records was technical progress: When reel-to-reel recorders appeared on sale, “bone” recordings became redundant.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox