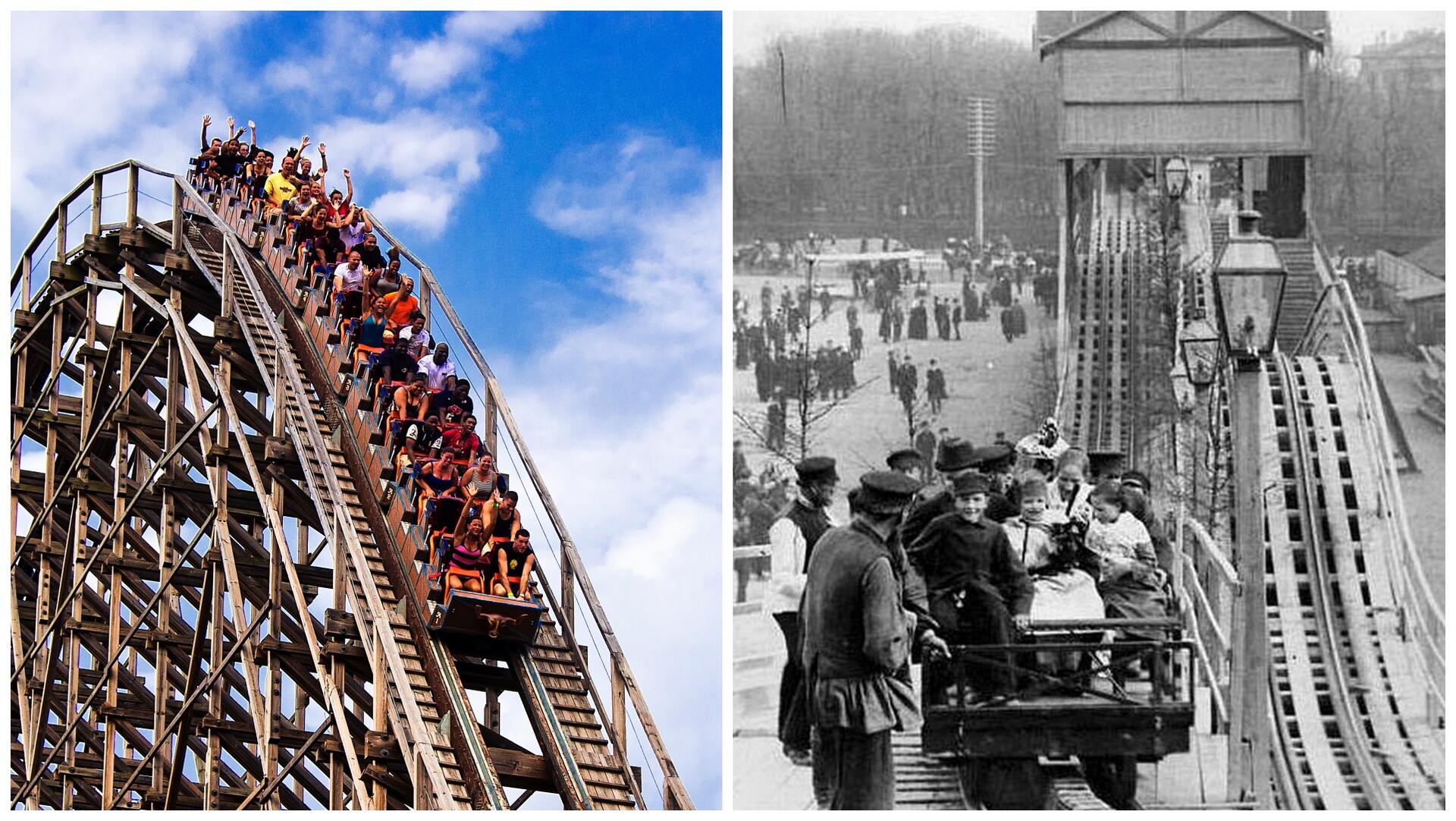

El Toro wooden roller coaster at Great Adventure Park in New Jersey, U.S. (L); “American” mountains in St. Petersburg, Russia, late 19th century

John Greim/LightRocket/Getty Images; Public domain

St. Petersburg’s Admiralteyskaya Square during Maslenitsa, 1850

Public domainOne of the boldest scenes of Nikita Mikhalkov’s iconic movie, ‘The Barber of Siberia’, is the scene of Maslenitsa festivities in Moscow. Among the entertainment is a huge wooden slope that people slide down.

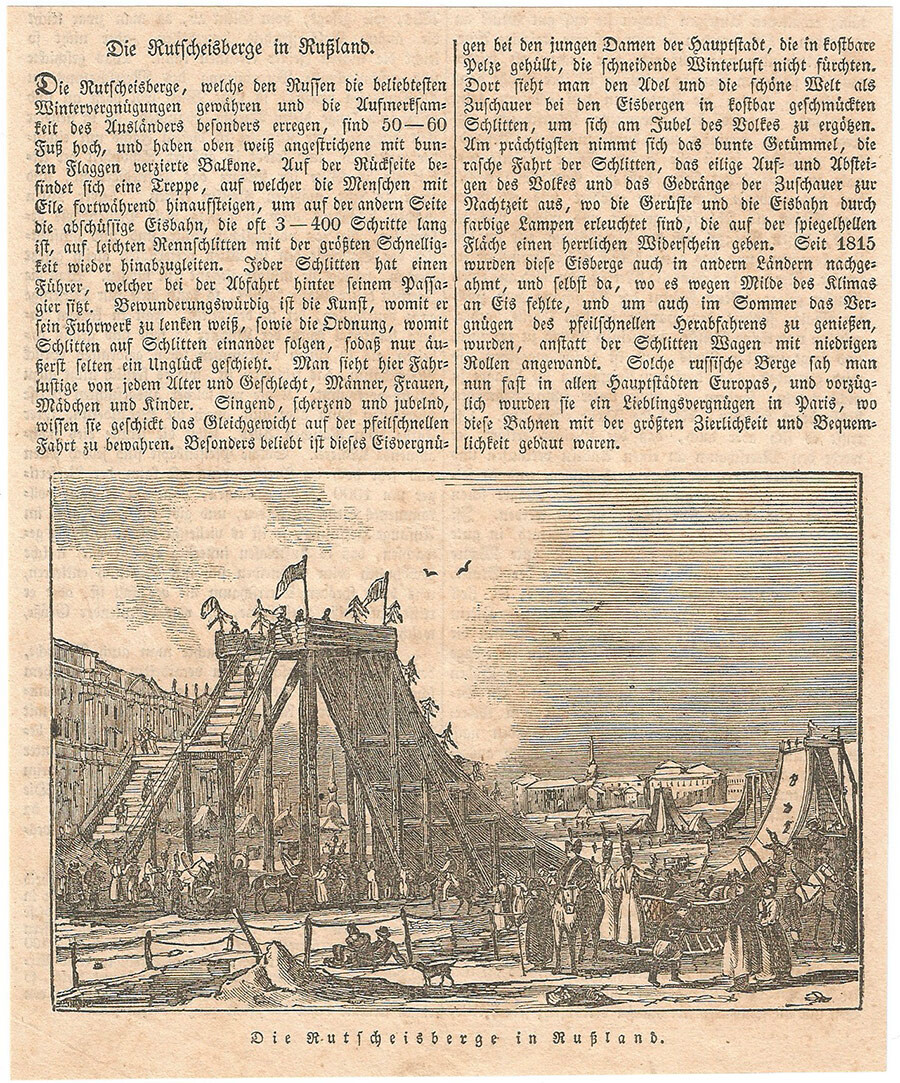

The Maslenitsa ice riding is exactly what’s behind the term “Russian Mountains”, which was adopted by several Romance languages in other parts of Europe.

Frederic de Haenen. Winter hill riding in Moscow

Public domainRussians had a rich history of winter entertainment. At this time of year, peasants were usually not that busy with work, so they made up different things to have fun. And one of the favorite things to do was to slide down a natural snow hill. The more people slide, the more the slope turns into ice, making it slide better. Then, people realized that they could simply cover any inclined surfaces with snow and water - and they turn into a great ice slope.

Maslenitsa was the festivities week at the end of winter, which was marked with enormous amounts of amusement, including riding the slopes. Big slopes were built in the big cities, including Moscow and St. Petersburg and people of any age and social status could join the fun of riding.

Maslenitsa in St. Petersburg. G. Broling. 1885

Public domain“Speaking of our Moscow winter fun, I should mention one amusement: the ice mountains, on which we rode during Maslenitsa, and sometimes, if the weather permitted, during Great Lent. Several of these Russian Mountains (as they were called in foreign lands) were set up behind our house, in the garden. We were allowed to ride them, especially because such movement in the clean air was good for health,” wrote Apollinariy Butenev, the Russian envoy to London in his memoirs in 1815.

Leonid Solomatkin. Maslenitsa

Public domainTsarist residences also had their own winter sliding slopes. Moreover, in the 18th century, Empress Catherine the Great decided that there is no reason to wait until winter to entertain herself. The Empire’s best engineers built a summer version for her, a Sliding Hill. This looked like a huge wooden ramp with three tracks more than six meters wide. The carts went down the middle track and then followed four slides going up and down. The carts moved forward by inertia more than 500 meters in total. After the ride, the carts were hoisted back atop along the side tracks with a special mechanism that was powered by horses.

A reconstruction of Catherine’s Sliding Hill

V. GavrilovRead more about Catherine’s Sliding Hill and see photos of its fancy pavilion here.

“Ice slides, which are a favorite attraction of Russians, arouse great curiosity among foreigners. The Russian slides are 50-60 feet high, with balconies painted white on top and decorated with motley flags. On the back side is a ladder, by which people are constantly climbing, so that on the other side on an easy sled ride with great speed down a steep icy slope,” reported the German ‘Journal of Publicly Useful Knowledge’ in 1835 calling the attraction - “Die Rutscheiberge in Russland” (“the sliding mountains in Russia”).

Many sources say it was Russian soldiers who reached Paris during the Napoleonic war and built small sliding hills on the Seine River. Soon the Russian attraction excited the Europeans so much that they started building their own slides in many cities. The climate conditions didn’t provide easy access to the ice even in winter, so they used cars with wheels to slide down.

“When winter comes, the Muscovites build high scaffolds in most of their towns, they attach a ladder on one side to climb them, and on the other side there is a quick slide down to rush in a sleigh on wheels... This very pleasure of the Russians was brought to Paris in 1816,” Claude Ruggieri, French festivities and fireworks specialist, wrote.

In 1816 one of the first famous sliding hill, called Promenades-Aériennes, appeared in Paris, and even King Louis XVIII attended the ride.

Promenades-Aériennes in Paris

Public domainLater, the entrepreneur Joseph Oller (who was also co-founder of the Moulin Rouge music hall) designed the Montagnes Russes de Belleville (Russian Mountains of Belleville) with a 200-meter track that looked like a double eight. So the Russian Mountains became a brand.

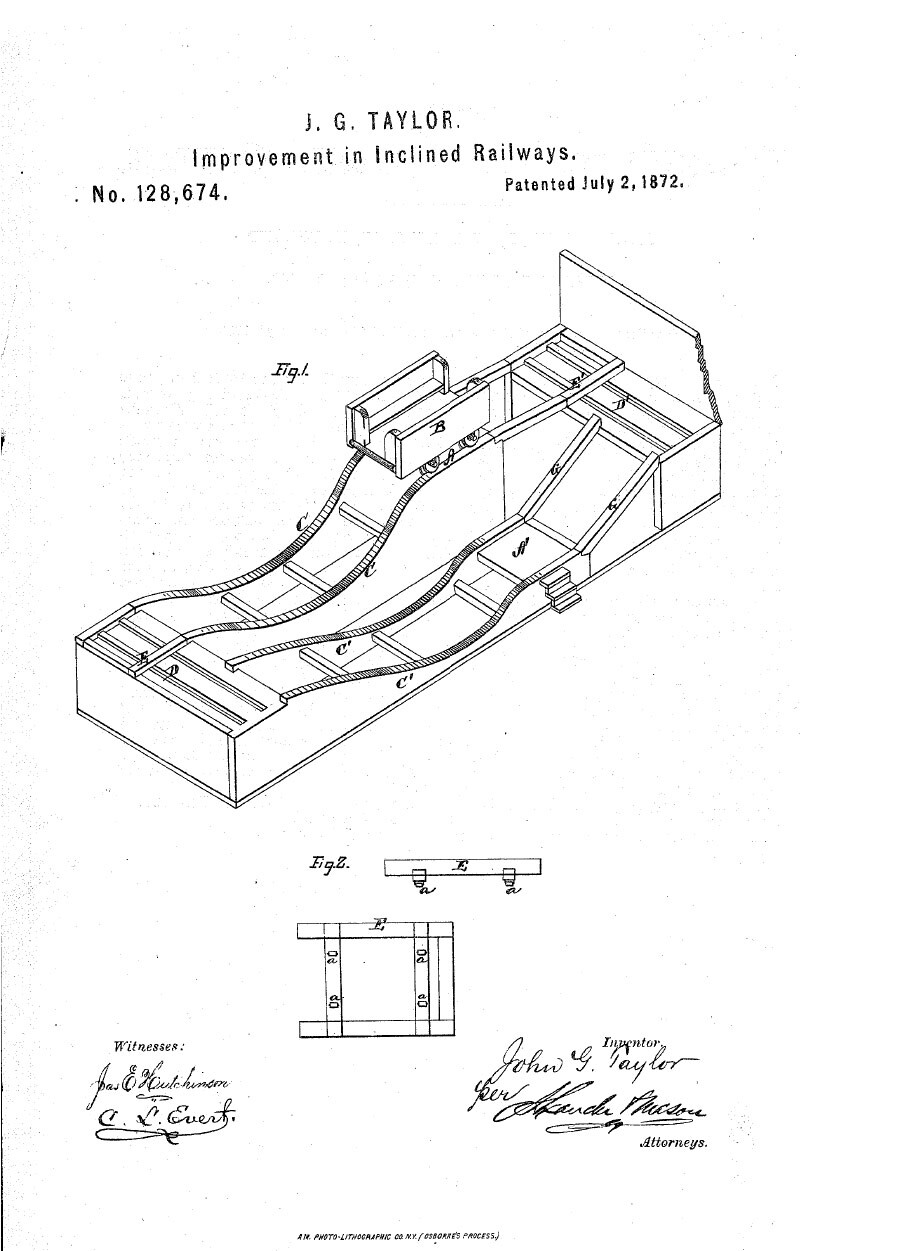

In 1872 John G. Taylor patented the so-called ‘Improvement of Inclined Railway’ in the U.S.. He created a project with a mechanism that switches a car from one platform to another so that it could run a different slope then (and would be lifted back as well). However, it's not clearly known if he managed to build such a railway.

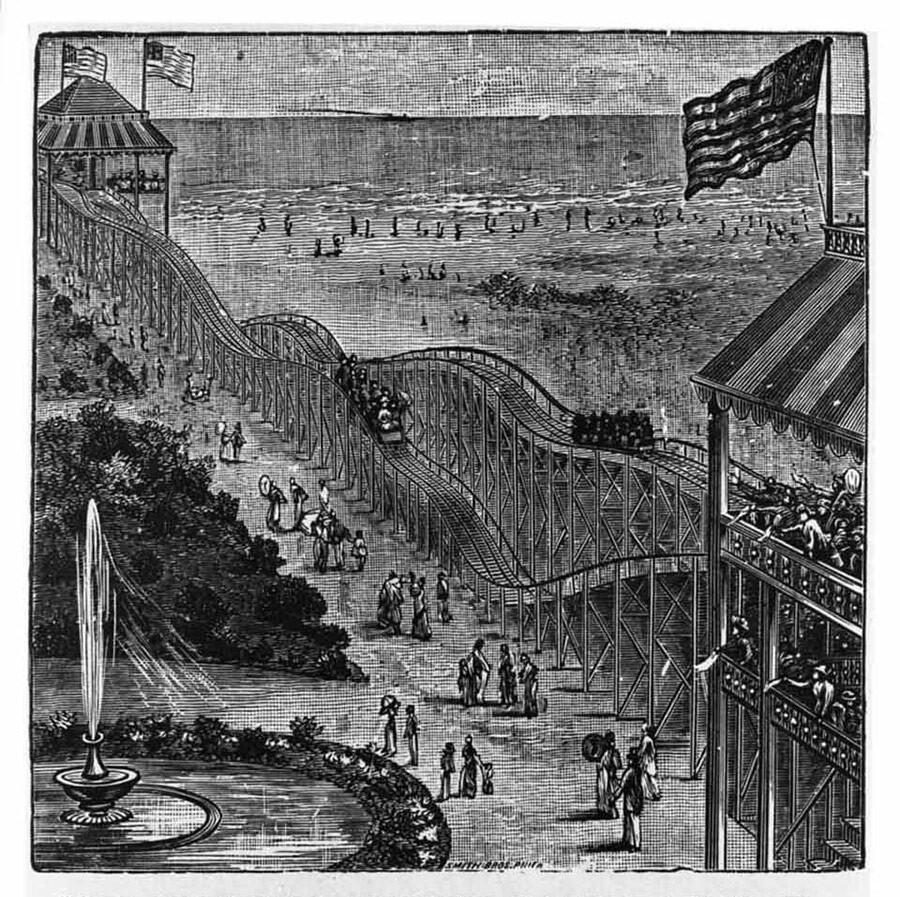

In 1885 the first widely known roller coaster was opened in 1885 at Coney Island in Brooklyn, New York City. It was called the Switchback Railway and was designed by LaMarcus Adna Thompson. A rider had to climb a 600 ft (183 m) tower and board a special car, and then slide off the wavy track to another tower - and then back. It resembles Catherine's Sliding Hill, doesn’t it?

Thompson was famous for developing the roller coasters and the so-called gravity rides and made it into the whole industry in the U.S. It was there when the mountains got their modern technologies (and safety system, because even Catherine the Great once almost fell from the cable).

So the new roller coasters reached Russia as well, and despite the fact that the whole of Europe knew them as ‘Russian Mountains’, in Russia they became known as… American mountains! And this is how roller coasters still are called in Russia.

“American” mountains in St. Petersburg, late 19th century

Public domainDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox