Something very similar to Russian felt-liner valenki boots were worn by ancient mountain dwellers in Altai. Archaeologists made this discovery almost 30 years ago while excavating the Ukok Plateau in the Altai Mountains. The permafrost has preserved nomadic burial complexes of the Pazyryk Culture that date back to the 4th–3rd century BC.

This region is now a borderland shared by present-day Mongolia, China, Russia and Kazakhstan, but back then only nomadic routes ran through summer grazing pastures and winter encampments.

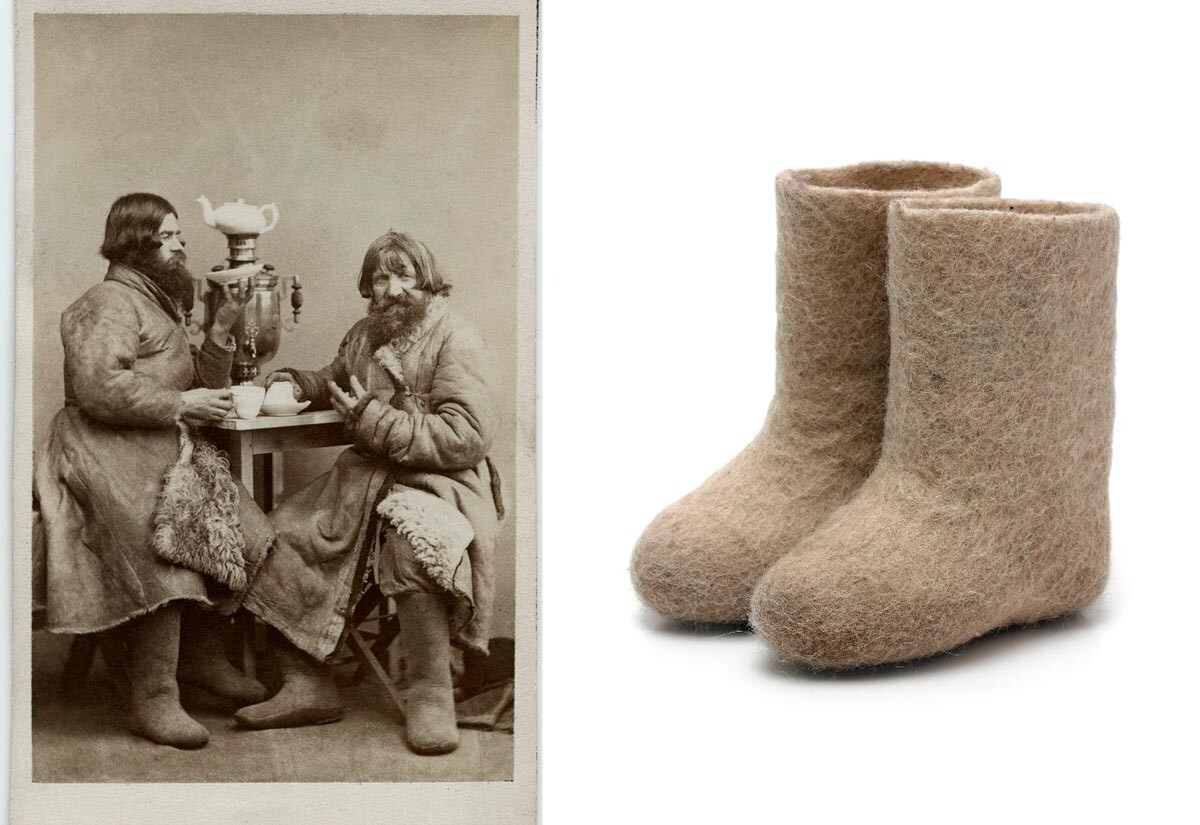

Felt was a common material used by all Central Asians, particularly among Turkic and Mongolian tribes. They used it to make clothing, carpets, quivers for arrows, accessories and footwear. In Russia's ancestral lands, the people made shoes from leather, bast fiber and fur. Their first encounter with felt boots was when the Mongols invaded in the 13th century. But even after the invasion, valenki didn't become a widespread phenomenon — only people who were fairly well-off could afford them.

The Russian take on valenki appeared in the late 18th century when Old Believers in the Nizhny Novgorod region invented a seamless felting technique. Then, industrialization made valenki affordable. The footwear began to be associated with Russia after 1851 when London hosted the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations.

Valenki later made guest appearances at the 1873 Vienna World's Fair, the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago and the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris.

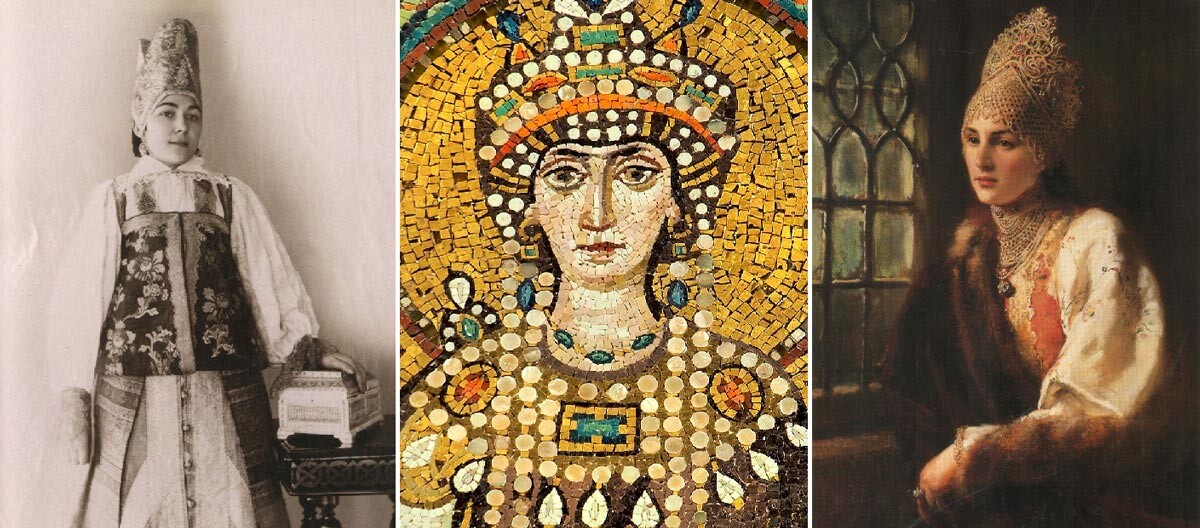

This iconic component of the traditional costume worn by Russian women has three proposed places of origins. According to one version, the headdress was imported to Rus from the Byzantine Empire. The royal daughters of Russian principalities are believed to have taken quite a liking to Byzantine tiaras at a time of heightened religious and cultural exchange.

Historians have found a headdress described as a comb and panel in the 11th-century Novgorod annals. According to another version, a similar headdress was worn by Mongolian and Mordvin tribes long before the Russian kokoshnik appeared.

Regardless of where the kokoshnik originally came from, it quickly caught on at a time when Russian women weren’t fond of wearing their hair down. A woman with her hair down was quite a frightful sight to behold, and it was a bad omen to see a girl with her hair undone according to Slavic mythology.

That's why the kokoshnik came in handy for women from all walks of life. The headdress, however, started going out of fashion with Peter the Great's social reform, when members of the court nobility were ordered to dress according to European styles. The kokoshnik was gradually consigned to the wardrobes of merchant wives, common townspeople and peasants.

The famous white-and-blue painted Gzhel ceramics first appeared in Russia during the time of Peter the Great. Like the rest of the Tsar's European borrowings, this cobalt-blue ornament was inspired by the Dutch Delft Blue — which is the distinct style of glazed earthenware produced by masters from the city of Delft in Holland.

A village outside of Moscow known as Gzhel was already the hub of Russia's pottery industry before it became the birthplace of the first Russian faience. During the reign of Peter the Great, Russians began painting ceramics in other vivid colors such as ocher, emerald green, and burgundy, depicting everyday scenes such as a graphic Russian lubok print.

They only later began imitating Delft Blue in the mid-19th century. On one hand, this was just a response to local fashion trends (including Chinese porcelain). On the other hand, however, artisans noticed that there was greater demand for monochrome Gzhel on the European market. The rich colors that are applied in multiple layers became Gzhel's signature brand and put the Russian village on the world map.

The iconic print variously known as cucumber, paisley and boteh is a very ancient pattern. It's believed to have originated at the beginning of the first millennium in the ancient Sasanian Empire. Also known as the Neo-Persian Empire, it now encompasses present-day Iraq and Iran. The ornament spread along trade routes to India, East Asia and Africa, only reaching Europe in the 17th century with returning British colonizers.

They're the ones who named it paisley. It wasn't until the next century that the pattern arrived in Russia, where it edged its way into the popular line of foliage patterns. The fresh cucumber print became one of the bestselling patterns produced by artisans at the Pavlovo Posad Shawl Manufactory, who make what are now probably Russia’s most world-famous headscarves.

This is another item with roots that can be traced to the barrow-like kurgan tomb mounds on the Ukok Plateau. The same excavation also uncovered a pointed felt helmet crested with a bird-head figurine that featured ear flaps that are tied.

It dates to the 4th century BC. This type of headdress later became common among Central Asian ethnic groups — Mongols, Kyrgyz, Bashkirs and Buryats. A pointed Mongolian fur cap with large ear flaps called the malakhay is believed to have been the prototype for the Russian ushanka-hat.

The ushanka has since been adapted many times but hasn’t been consigned to the history books. It was introduced into the Red Army's winter uniform in 1940. The Mongols may have valued the malakhay for its protection against arrows, but the Russians simply appreciated their ushanka for its heat insulating properties.

In the harsh Russian winter the ushanka was indispensable for peasants, soldiers and tsarinas alike. Peter the Great's mother even had three in her wardrobe!

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox