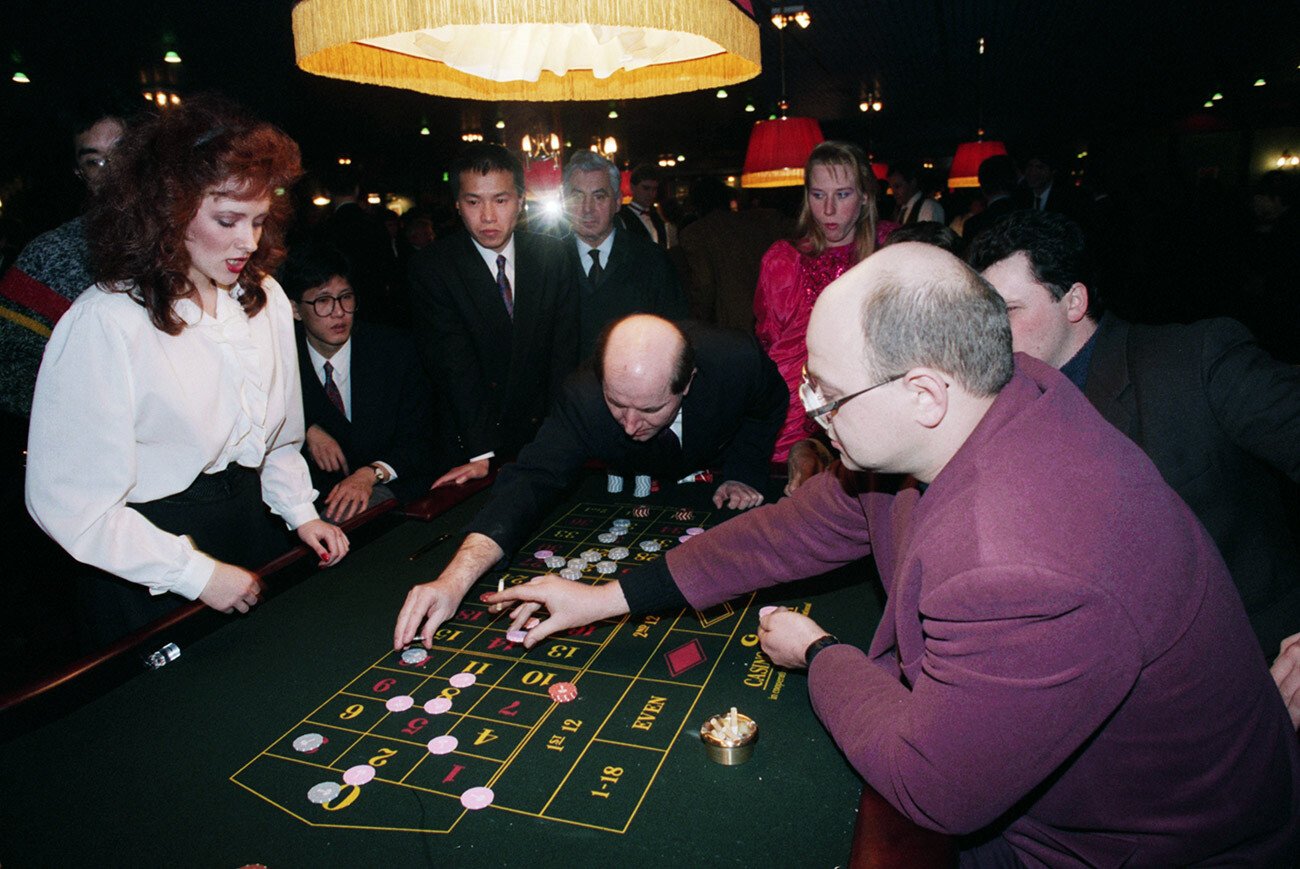

Shot from the film "Dead Man's Bluff"

Alexey Balabanov/STV, 2005Hair shaved at the back of the head, raspberry red jackets, gold rings and the Mercedes Benz W140 (known in Russia as the ‘shestisoty’ - the ‘600’)... For those who lived in Russia in the 1990s, the image is painfully familiar. A typical ‘new Russian’.

The concept of the ‘new Russian’ on the territory of the former USSR was first used in an article in the Kommersant newspaper in 1992 (and refers to Nouveau riche). Initially, the phrase applied to people who were well educated, had good career prospects and were regarded as the “topmost class” in society. “The emergence of the term was largely accidental - it was invented for fun,” according to political analyst Georgy Bovt.

So, why “new” Russians? The thing is that after the collapse of the Soviet Union, ordinary citizens who had lived until then in a planned economy (in which there was no private property and entrepreneurship was banned), suddenly found themselves in a world where people could engage in whatever business they fancied. Those who were fastest to fit into the new system and make a fast buck out of it began to be called ‘new Russians’.

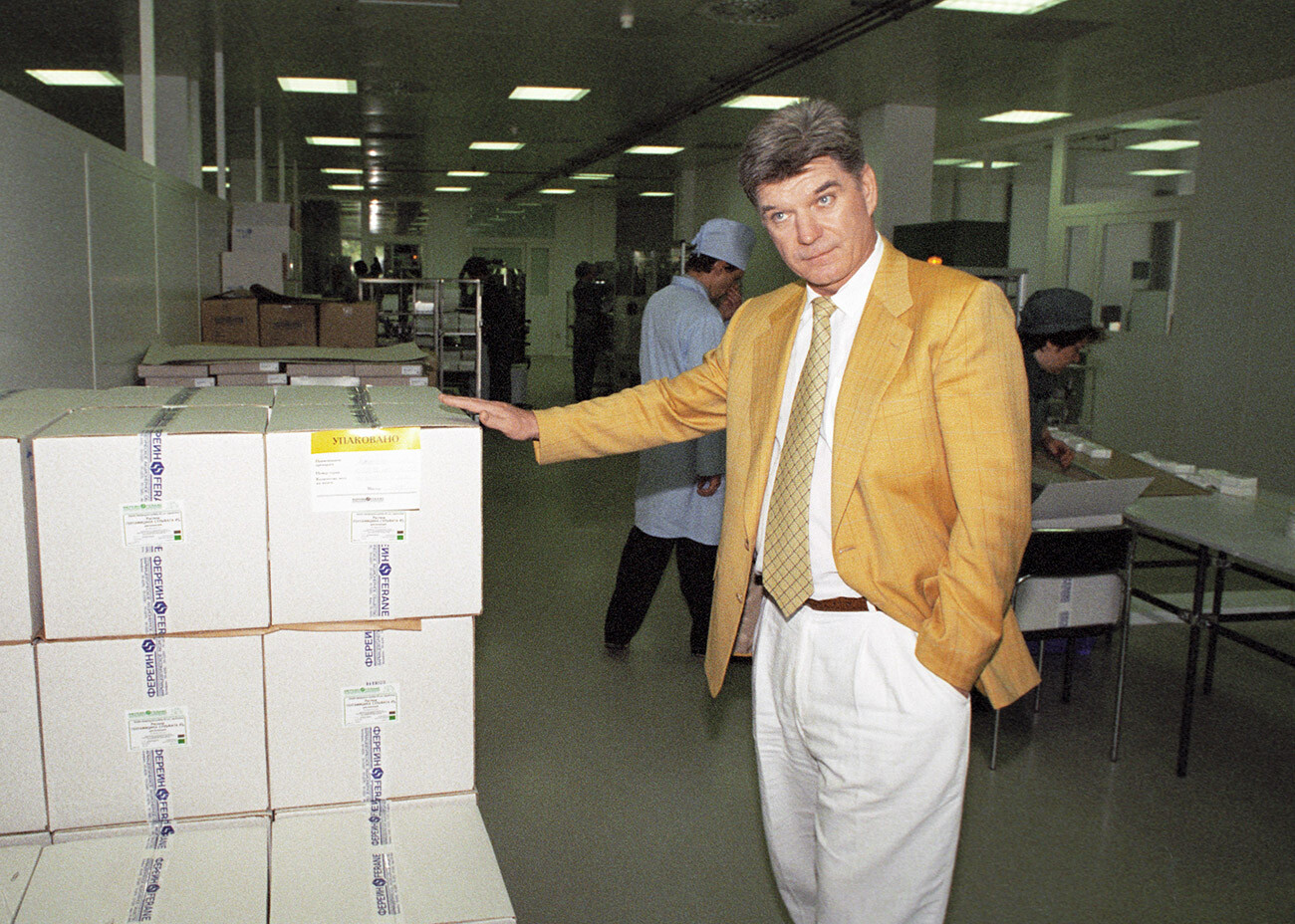

Showman Stanislav Baretsky

Sergei Konkov/TASSIn most cases their main activity was trading. In particular, they traded in goods that were in short supply and foreign goods: clothes, electronics, cosmetics and much more. Those who managed to find business partners more quickly than anyone else, bring the goods to Russia and find “sponsors“ here to protect them from other newly minted wheeler-dealers were guaranteed to become rich and successful.

The ‘new Russians’ were among the first to begin to travel abroad on a regular basis and establish contacts with potential business partners in the West. “The ‘new Russians’ were well received there and people wanted to strike deals with them,” according to Georgy Bovt.

It was all because many in the West believed that, sooner or later, a middle class would emerge in Russia and the country would become a model capitalist state. But, in the second half of the 1990s, it became clear that things were not that simple and that big business was run by people more often than not associated with crime.

“Their success was based on the ability to make money out of anything - moreover, in the 1990s, this meant profiting from the woes of society at large. That is why, in the popular imagination, a ‘New Russian’ is a negative figure,” according to Andrei Timin, who, like many in the 1990s, quit academia and went into business, becoming a ‘new Russian’ himself.

Closer to the mid-1990s, the label ‘new Russian’ was applied not to the “topmost class” in society, but to people with big money and criminal connections. Frequently, these connections implied trading illegal commodities like drugs or arms.

The ‘new Russians’ were like a subculture: with their own style of dress, trappings and way of life.

The most noticeable symbol was the raspberry red jacket. It is unclear why exactly jackets had to be this color, but there is a theory that the fashion was set by Sergei Mavrodi, the founder of one of the largest financial pyramid schemes to have been set up on Russian territory. He once went on a TV program dressed in such a jacket and, thereby, seemingly “set the trend”.

Fashion historian Megan Virtanen believes there is also symbolism at play: Purple and raspberry are colors denoting power and wealth and ‘new Russians’ were instinctively mimicking this notion.

They were also fond of the trappings of the “good” life: Gold accessories, large wristwatches (the slang term for one was ‘kotyol’, meaning ‘pot’) and signet rings on practically all the fingers of both hands.

Sergei Mavrodi during a televised address

Youtube.comAlong with the gold jewelry, they wore high-end designer clothes (not always originals, it has to be said) and also drove expensive cars: the Mercedes-Benz S-Class (nicknamed a ‘Merin’), the BMW 750iL (a ‘Boomer’ - the Russian equivalent of the Western ‘Beemer’), various Audi models and other upmarket car models.

The ‘new Russians’ did not disappear in a day, but gradually evolved into different things. With time, some of them “morphed” from common gangsters in raspberry red jackets into respectable, conventionally-dressed people: They became individuals with more power, more money and a different circle of contacts.

Others opted for self-education and went into legal business ventures. And others still simply ended up dead. Given their links with the mafia, this was not unusual in those days. It might be mentioned in passing that, even after their deaths, these people contrived to stand out from the crowd. The memorials to former ‘new Russians’ can be spotted from afar at any Russian cemetery: massive structures, lifesize statues and sometimes whole vaults.

By the early 2000s, when the repute of the ‘new Russians’ had already peaked, this class of people became an object of caricature for many: the wheeler-dealers in raspberry red jackets became the stereotyped protagonists of ironic jokes and movies about the “businessmen” and the circumstances of 1990s Russia.

At the same time, their impact on their age was enormous. Cellphones, credit cards and holidays at Antalyan resorts all became part of the everyday lives of ordinary people, thanks to the ‘new Russians’ having set the trend for a more affluent lifestyle. The wheeler dealers in raspberry red jackets demonstrated that it was possible to make easy and quick money - the new country that all the inhabitants of the former USSR found themselves in offers many more opportunities for self-realization and generating an income. The ‘new Russians’ were the embodiment of 1990s Russia, a country in which anything could be achieved if you knew in time what you needed to do to get it!

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox