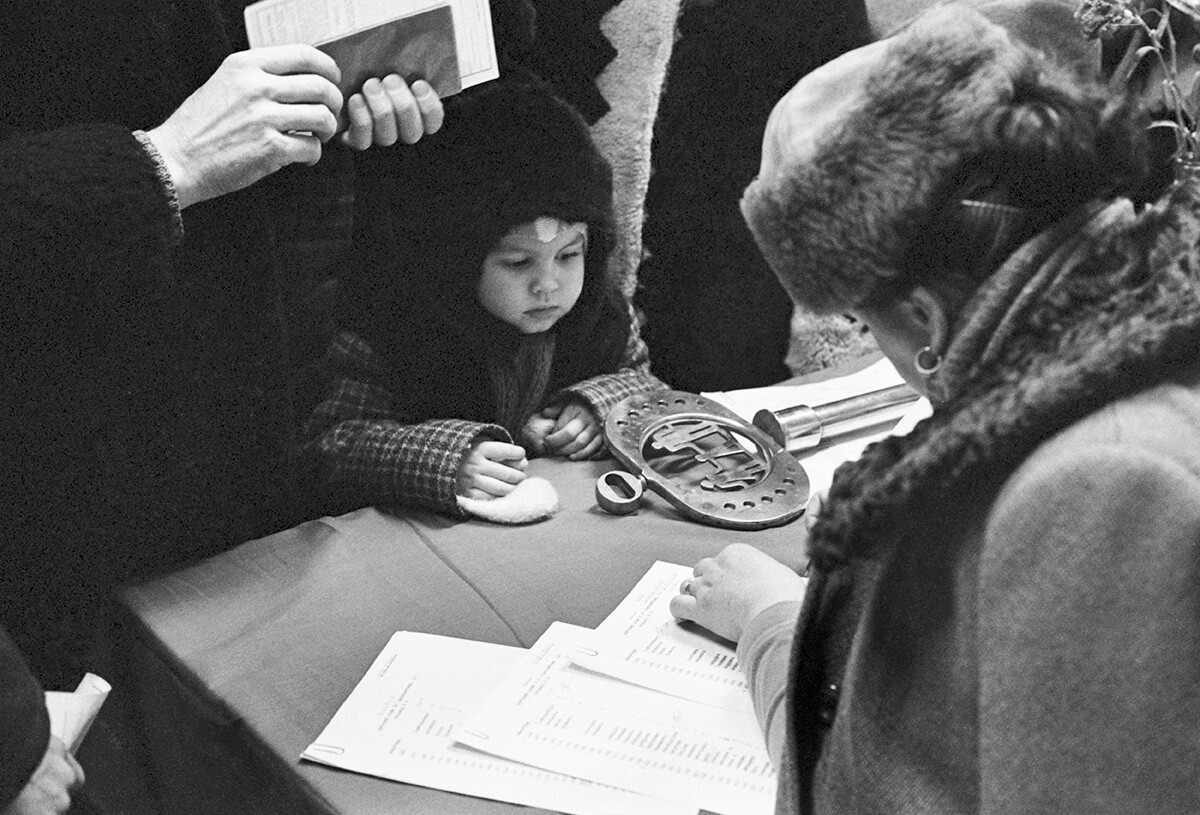

At the housing swap bureau of the city of Omsk

Alexander Kositsin/TASSThe government controlled the vast majority of real estate in the Soviet Union: it decided on who received a new apartment and who was to be deprived of the chance. There was no such thing as a “market”, in the capitalistic sense of the word.

In order to secure an apartment, a person or family would have to get on a waiting list for “improving living conditions”. Anyone could apply, if their household allowed for less than 9 sq. meters of space per person. However, the waiting list could be six or seven years long.

Another method was to become a lifelong caretaker of an apartment: you could live there for free, but it wasn’t your property - you couldn’t sell it, gift it or pass it on to your children.

The first phase of market liberalization arrived in 1958. Residential unions, through which one could buy an apartment, had appeared across the country. The price per sq. meter was fixed between 6,000-8,000 rubles - an unimaginable amount for a regular Soviet person. The sum would be split into several parts (akin to a mortgage); however, the first installment was still too great for most people. Therefore, such living spaces accounted for only around 10 percent of all real estate. And, if someone were to decide to sell a union-bought apartment, they had to secure permission from every member of the union and still sell at the original, fixed value.

As a result, people searched for ways to circumvent the rules that prohibited private dealings. Swapping apartments was one of them.

A widespread type of deal was to exchange apartments of unequal value, with one side paying extra; transactions of this kind were difficult for the government to track.

“Each Sunday at the bazaar, you would come upon crowds of people holding up little paper posters with things like ‘Will change a 3-bedroom for 1+1’. They would disperse in seconds at the sight of the police,” remembers Tatiana, whose close friend Irina had the uneasy job of being a middleman in those street deals. Such individuals were referred to as ‘maklers’ (‘brokers’) and they were the only people in the Soviet Union who could help with exchanging apartments with another person.

‘Maklers’ existed in a legal gray area, but were the only ones that could save you the trouble of looking for an apartment on your own and having to engage in multi-level deals. More than one family would often participate in the exchange chain - sometimes, as many as 10, in fact. Each would get what they were looking for in the end.

However, someone needed to control what was happening in these complex schemes, so they didn’t collapse, leaving the participants without money or a new apartment. After all, this type of agreement was practically illegal.

“You could ‘sell’ [exchange apartments with one side paying extra] an apartment through a fake marriage,” Gennadiy Meshutkin remembers. He used to be a ‘makler’ in the 1980s and currently works in real estate. “An apartment resident could enter into a matrimonial contract, register their spouse, then get divorced, move out and receive the money.” However, this was a lengthy and cumbersome approach to exchanging apartments; besides, both the seller and buyer could face unforeseen circumstances, so not everybody was willing to risk such an arrangement.

A skilled ‘makler’ was a valued member of society and did their best to preserve their reputation. Given the questionable legality of such work, word of mouth – recommendations from people and other ‘maklers’ – was the only way to ensure that. However, the service wasn’t cheap by Soviet standards, often costing 200-800 rubles per deal; again, due to the risks associated with such an illegal undertaking: if a ‘makler’ were caught, they could face a three-year prison sentence, with all of their property confiscated.

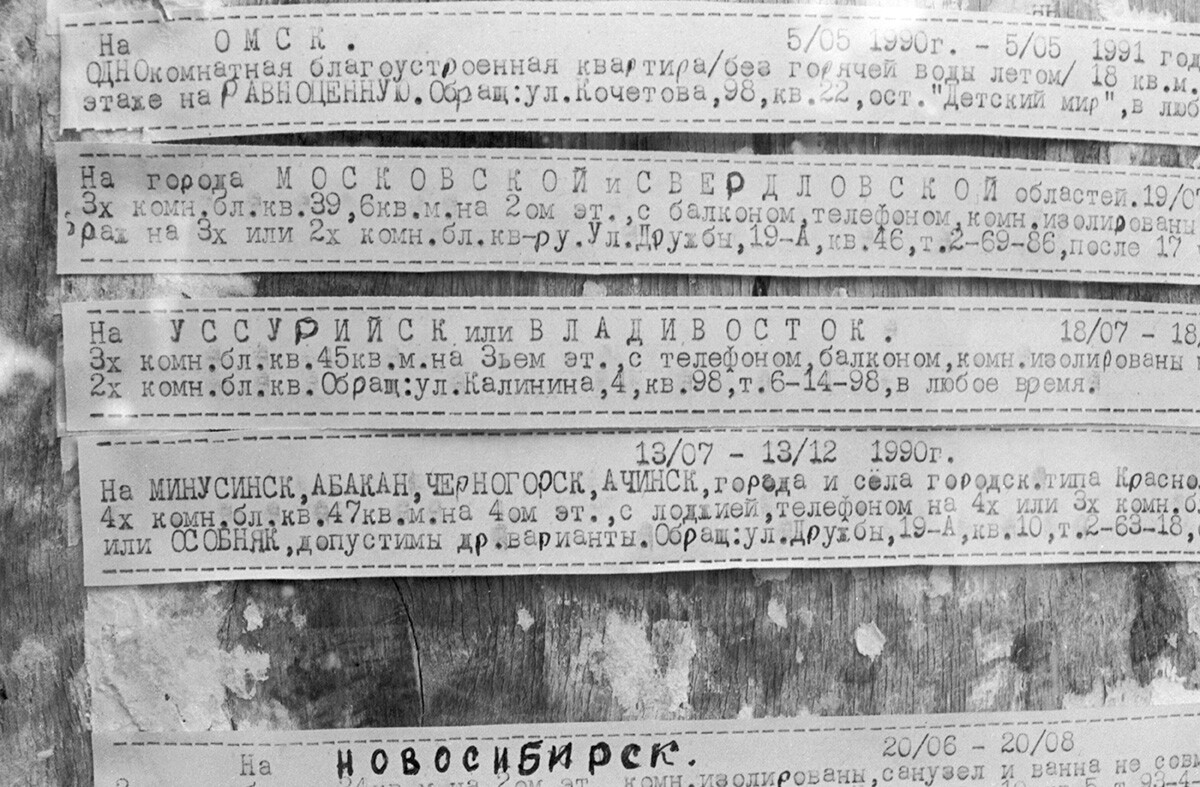

In the early stages of these exchange schemes, people would publish classifieds in newspapers, looking either to exchange one city for another or find another apartment in the same city. A certain level of ingenuity was required to keep from getting caught by the authorities. However, with the arrival of ‘maklers’ on the scene, the situation had somewhat improved and newspaper classifieds had given way to real-life deals.

‘Maklers’ could be found at particular meeting spots, where they would exchange the latest information – for instance, on potential clients or what newspapers to look in and so on. Potential clients would occasionally show up in person, to finalize the specifics of a deal, find a potential exchange partner to add to the lengthy chain of participants and agree on apartment viewings. One of the most popular spots was Banny Pereulok in Moscow.

In order to not be overcharged by a ‘makler’, many people would visit the bureau like it was their workplace, to scope out potential apartments all day long or check out the latest classified stands.

“Irina exchanged her parents’ three-bedroom for two single-bedroom apartments - one for herself, the other - for her parents,” Tatyana recalls. “But, after the birth of her son, she understood that her and her husband’s jobs weren’t the kind where they could hope for any sort of handout from the state. And, although the husband wasn’t a low earner by any means, getting an apartment through the residential union wasn’t on the cards. So, they decided together that she absolutely needed to earn enough money for the coveted three-bedroom. And she did.”

“At first, Irina and her husband dealt in other people’s properties, sometimes with 20 families in her exchange chain at once. The swaps would result in many clients losing at least a couple of square meters in living space. However, Irina - having included her single-bedroom apartment - actually gained a few meters in the end,” Tatyana continues. “She and her husband then had their fake divorce and the large 1-bedroom apartment was split into two smaller rooms. Once that was done, she would again flip the resulting apartment for a bigger one and so on and so forth. About 10 years later, they had their own large four-bedroom apartment and about a dozen moves under their belt.”

It was, however, easy to encounter unsavory characters in the course of these personal exchanges.

“I worked at it like a freaking woodpecker for six months,” writer Maria Arbatova recalls. “We’d looked at a ton of apartments by then, each with its own story. And there was this type of people - predominantly consisting of the elderly - that loved to play the swapping game simply because they were bored and it amused them. You arrive at someone’s home, begin to go over the particulars, finalize a deal - and then, the following day, they call you and tell you they’ve changed their mind.”

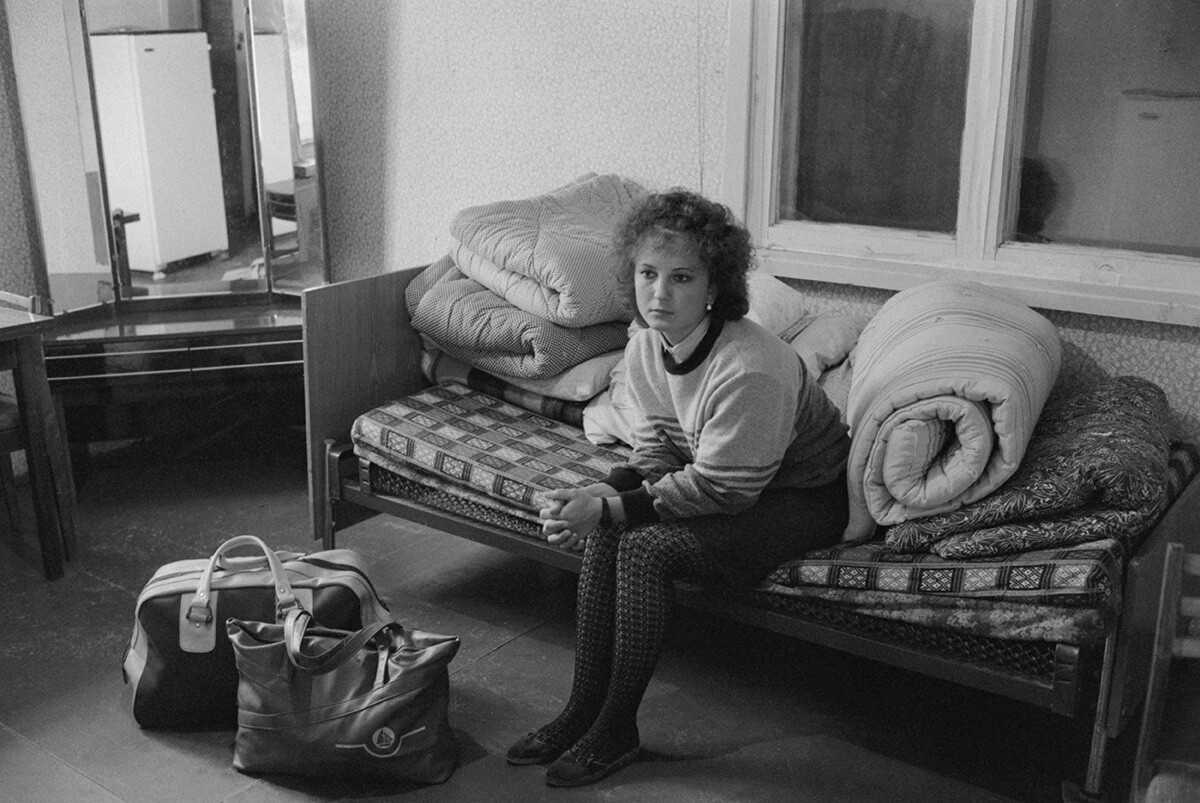

The golden age of broker-assisted real estate swapping came to an end with the breakup of the Soviet Union. In 1991, the law ‘On the privatization of the residential fund’ opened the door to the era of private property. People had now had the right to swap, buy and sell to their hearts’ content. They could also privatize a formerly state-owned property they’d lived in the entire time (although, some are still on the waiting list to finalize such a deal to this day!). Others managed to purchase their own apartments, since it was now legal.

The ‘makler’ market quickly dwindled, with the population beginning to learn the ropes of functioning in a market economy. However, many of the brokers didn’t change professions - they simply became legal real estate agents.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox