“You know, I've been to many places and I can tell you this: In Australia, I'm freer than in America, in Europe, I'm freer than in Australia. But, in Russia, I am freer than anywhere else!”

Born in New York, Jay Close has traveled the world in search of himself: He has worked on a crocodile farm in Papua New Guinea, as a trucker, as a chef in a Parisian restaurant and much more. But he only really truly found himself in Moscow: When he first visited in the 1990s, he eventually decided to become a cheese maker. Now, on his farm in the village of Moshnitsy in the north-west of Moscow Region, he produces 50 types of cheese, while also promoting agritourism.

He first met Russians in the early 1990s in Paris. At the time, he was working in a restaurant as a chef and they had guests who spoke an "incomprehensible language", as he said. Among them was Russian fashion designer Valentin Yudashkin, as well as singer Iosif Kobzon's son Andrei.

“Russia was a taboo subject in America. Propaganda was doing its job,” Jay says.

“So, here I am, 30 years old and I'm meeting Russians in Paris. As a chef, I show them the club and the restaurant. Then, we made kebabs on my yacht. Then they visited again and again.”

One day, they called and invited him to come with them to Moscow. Jay was interested in seeing ordinary people and he chose to live in a residential neighborhood on the outskirts of the city. "There were no stores like there are now. If you needed clothes, people would go to the market, the seller would throw a piece of cardboard on the ground and you had to stand there to try on jeans. Others stood near the subway: one with a chicken, another with children’s toys. And, if you asked them what they did for a living they’d say: ‘I’m a businessman!’ Of course, it was something surreal!”

Jay became independent at an early age. Already at the age of 11, he was scrubbing floors at a furniture factory and, at 14, he moved to a crocodile farm in Papua New Guinea. “My job was to give the crocodiles frozen fish on the end of a stick. And I had a little crocodile of my own, I used to put it right in my shirt and to school with it. When the teacher didn't look my way, I’d show everyone the crocodile. It was fun!”

Jay trained as a chef in the U.S. and worked in California, Australia and Europe. Having moved to Moscow in the 1990s, he became a chef in various restaurants and clubs in the capital and on private boats.

When he worked at the ‘XIII’ nightclub, he even managed to invite both Marilyn Manson and Harrison Ford, who were in Moscow, to one party at the same time.

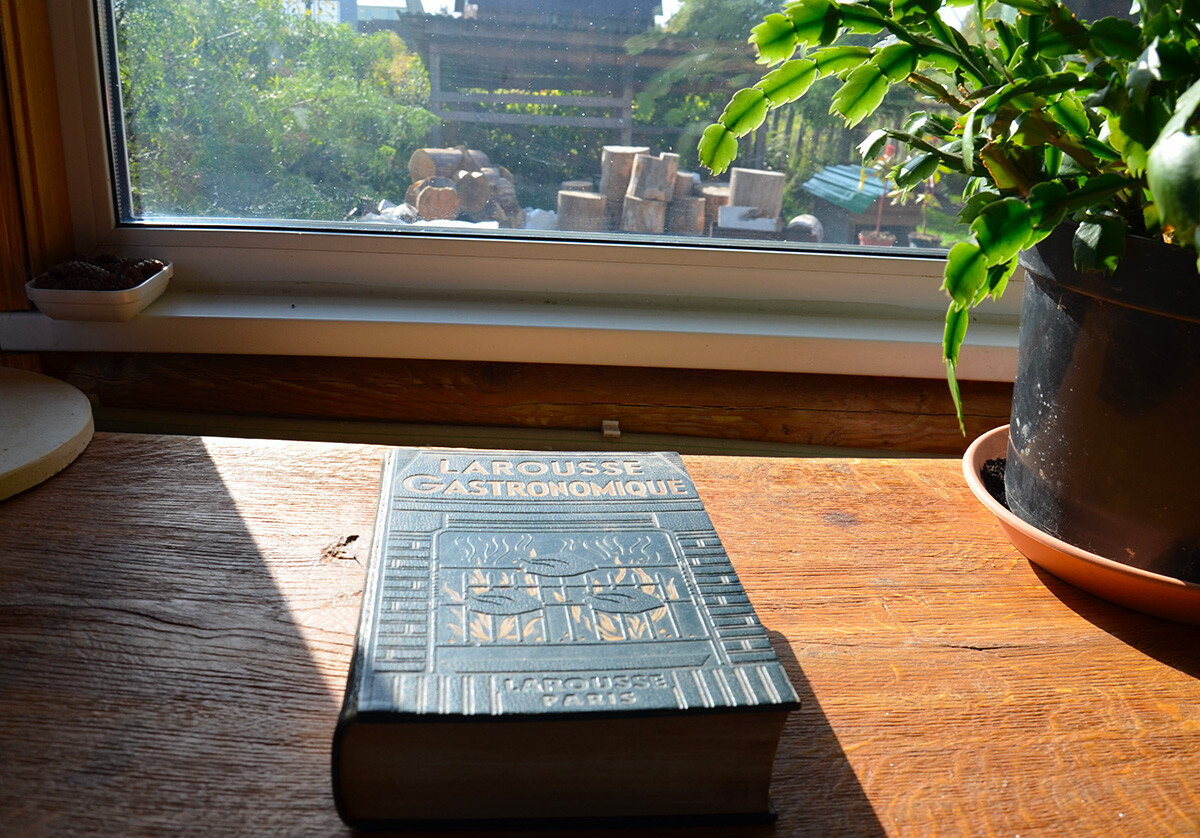

One day, Jay saw an ad in the newspaper selling a piece of land in the village of Moshnitsy. He knew nothing about farming, but his girlfriend convinced him to get a cow and a bull. “We bought a few animals, we got a calf and we started to get 30 liters of milk a day. What to do with it? I decided to make cheese! I flew to Holland and, there, I found some cool craftsmen who taught me. And now, for 15 years, I have been making cheese in Russia!”

“Real milk comes in four types: spring, summer, fall, winter. The cow's diet is different and the compound nutrition is different. My cheese is made from 'no middleman' milk, just like in the old days. And it has a different flavor in each season.”

He called his cheese factory ‘Jay's 33 Cheeses’, although he now produces over 50 types of cheese. Gruyere, cheddar, marble cheese with red wine and black truffle cheese, Swiss lace and many more!

These days, Jay sells more than 150 kilograms a week. His adult son Zakhar helps him.

“You can also order online, but people prefer to visit, see and talk. And, every time, they ask the same thing: 'How do you like it in Russia? Why did you come? Is it really better here?’”

“Many Russians go to [the U.S.], they spend a year or two there and come back: it's difficult there. There is a lot of bureaucracy. I, for example, could not do this kind of business. In America, you can't sell cheese made from unpasteurized milk. You can't even give someone cheese or milk from your cow as a gift, it's forbidden by law. And it's done on purpose, so that big companies have a monopoly on trade. They're not interested in family business. If you want to buy a gun, no problem, but fresh milk is a terrible weapon!”

Jay says that Russia is interesting to live in and that he regrets not having visited it under the Soviet Union. "It was explained to us in America that it was determined who would work where. But, I saw, no, people did as they wanted."

“And I also wanted to find out for myself the difference between your pioneers and our ‘Boy Scouts’. They did the same things – they sang hymns, went on hikes, loved their homeland. But, the propaganda said that scouts were good and pioneers were bad.

“You know, I've been to a lot of places and I can tell you this: in Australia, I am freer than in America, in Europe, I am freer than in Australia. But, in Russia, I am freer than anywhere else!”

On what freedom is, Close tells us simply: it’s the ability to choose your profession, to do what you want to do.

“When I go to another place, after five days, I expect to be back in Russia, back home.”

Jay says that, although he has lived in Russia for 30 years, he still feels like a foreigner with many cultures mixed together. “But, my children were born here. Here, I have a house, a farm, friends and many ideas for the future. And I’m happier here than there – that’s for sure.”

The article was originally published in Russian for the Nation magazine.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox