Today, Yekaterinburg is a very comfortable, modern city. But, German native Alexander Kahl admits that many Russians did not understand how he could even live there in the early 1990s. After all, at that time, it was almost the most criminal city in Russia.

“We arrived in Yekaterinburg at night, walked out of the station in total darkness. There was only one illuminated street for the whole city at that time – Lenin Avenue. And we walked by feel, pushed by the excitement of youth,” recalls Kahl with a smile.

Then, he even bought a flashlight, because in the city of Yekaterinburg it gets dark early, already at 4 p.m.

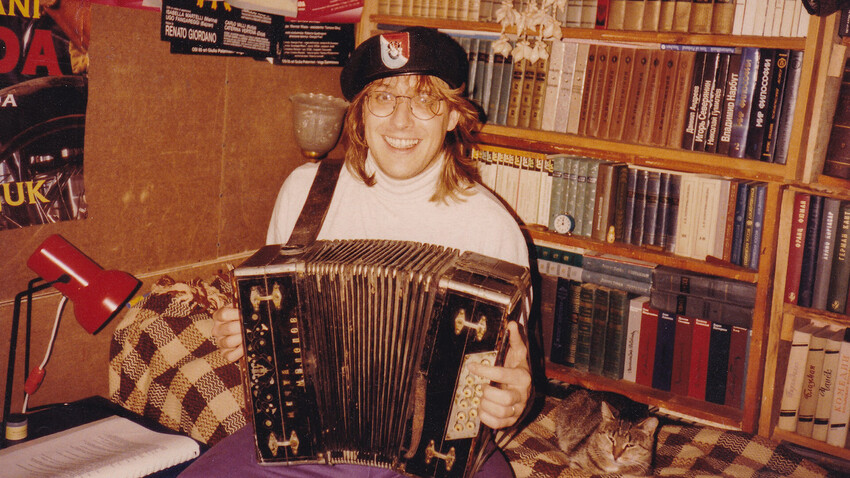

Kahl and Kolyada at the market, 1990s

Personal archiveEverything was unfamiliar. In the apartment, brown water flowed from the tap, in the stores, you had to ask for goods in one place and pay for them in another.

“But, I did not evaluate this new life in the category of ‘bad-good’, I was excited about everything. I got into another world, I was learning to understand it. And, if it scared me, I wouldn't have stayed.”

Alexander went to Russia to translate contemporary Russian plays into German. He was invited by Nikolai Kolyada, then an aspiring playwright and now the director and head of Russia's most famous private theater, the Kolyada Theater.

Kahl comes from a small town of Lörrach with 50,000 inhabitants. He had always dreamed of leaving it to see the “big world”.

Alexander was fond of theater, but his rational father discouraged him from tying his life to it and suggested choosing a more practical profession.

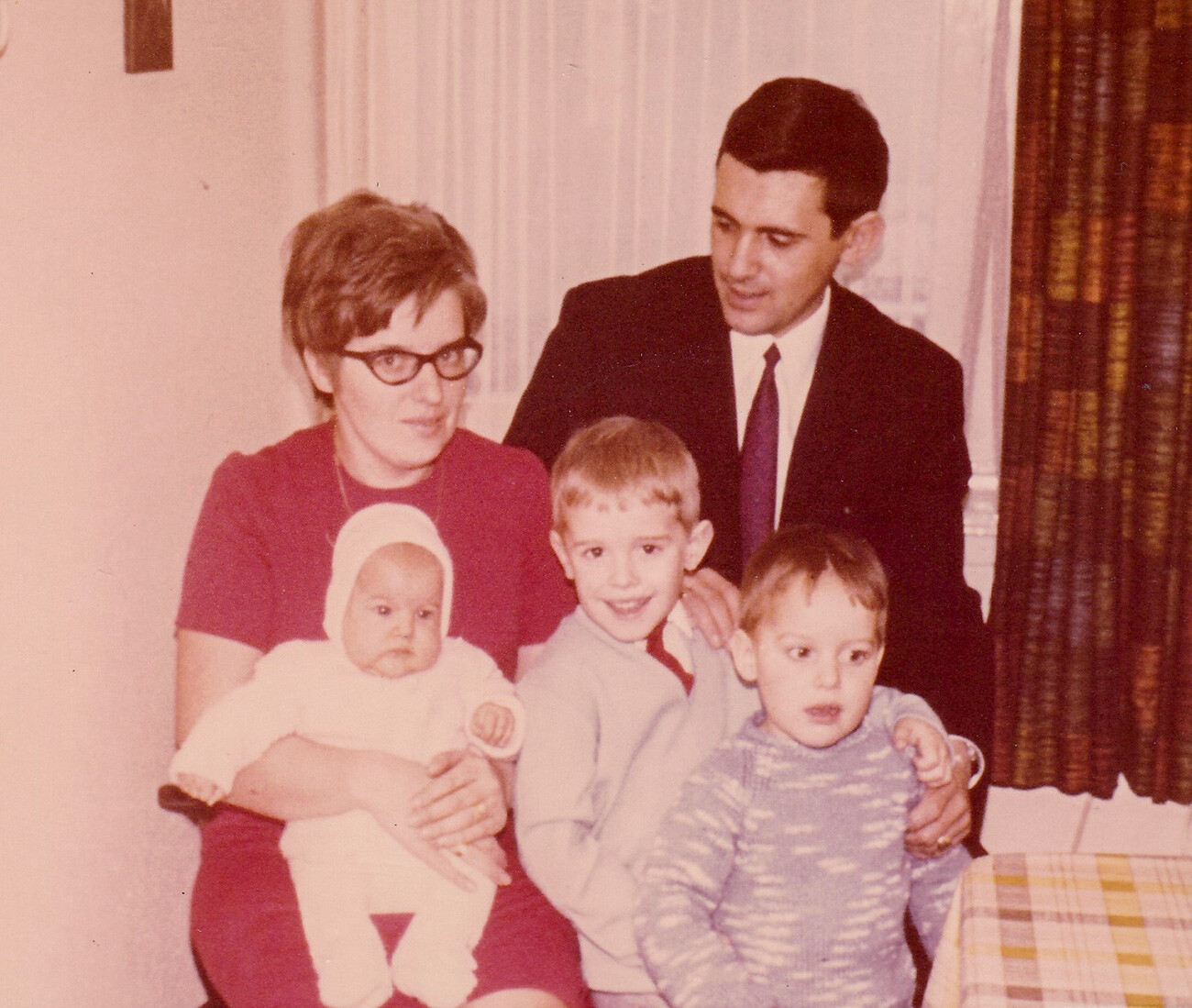

Alexander Kahl (a boy on the right) and his family, 1968

Personal archiveIt was the mid-1980s, when Russia, China and Japan were beginning to open up to the world. But, there was a shortage of linguists proficient in these languages. Kahl wasn't much into Asian culture and hieroglyphics. So, he chose Russian and enrolled at the Free University of West Berlin.

In addition, the German was already familiar with Russian literature – back in school, he had read Solzhenitsyn's ‘One Day of Ivan Denisovich’, as well as Dostoevsky, Tolstoy and Turgenev.

In 1989, East and West Germany united and Kahl became a student at the Humboldt University in East Berlin.

There, the Department of Slavic Studies held many seminars on Russian culture. At one of them, the German met Russian playwright Nikolai Kolyada.

Alexander Kahl (right) and Nikolai Kolyada (left), 1990s

Personal archive“He was very open, answered all questions and beckoned us to visit. A month later, we, the German students, were invited to Moscow for an internship at the Pushkin Institute.”

Kolyada got the Germans tickets to various productions and they began avidly absorbing Russian theater and getting to know living legends.

It was Kolyada again who invited Kahl to Yekaterinburg. In the early 1990s, he organized the international ‘Kolyada-Plays’ festival there and then his own private theater. Kolyada was looking for a translator of his plays into German, so that they could be performed in German theaters.

He was dissatisfied with all the translations that had been done before, because he knows the language well.

Kolyada Theater

Svetlana Lomakina“The first play I translated was called 'The American'. He liked the translation. We found a publisher and signed a contract for five plays.”

In total, Kahl translated 112 Russian plays, not only Kolyada's, but by other authors, as well.

After 10 years of living in Russia, the interest in translations waned somewhat, so Kahl had to look for another job. At first, he worked in television, talking about the cultural life of Yekaterinburg, and was even nominated for the TEFI award as a presenter. But, the default of 1998 hit and the project closed down.

Working on TV in Yekaterinburg, 2000s

Personal archiveSo, gradually, the German went into linguistics. “What my dad had advised came in handy : languages.”

Now, Alexander Kahl teaches at the Department of Linguistics at the Ural Federal University and runs the German Language Center.

In order to convey the nuances of Russian life when translating the plays, Kahl had to explore traditions, customs and proverbs in detail. For example, what is a village wash-hand-stand?

“I could call Kolyada any time and ask him: why shouldn't we say hello across the threshold?"

Kahl and famous Russian actress Valentina Talyzina, 1990s

Personal archiveAt first, in Russia, Kahl lived in the playwright's apartment. And, once, Kolyada was his guest in Germany. Every day, Kahl asked his Russian colleague if he wanted to have dinner. And the playwright answered: no.

“And then, it turned out that he went to bed hungry all this time. Because Russians have a habit of coaxing: please, sit down, eat, come on. And I didn't know that and, like a German, I didn't want to push, to impose…”

Germans have order, discipline and vice versa Russians rely on luck, on their untranslatable 'avos'. And the Germans are used to this peculiarity. And used to the fact that Russians are always late.

With famous actor Sergei Makovetsky (on the left) and Nikolai Kolyada (on the right)

Personal archive“Although, I have not changed in this regard. And I demand from my students that they show up on time.”

The only thing Kahl really had to get used to was Russian cuisine.

“What I really had to put up with in Russia, at first, was this awful dill! In the past, no matter what you ordered, they put it everywhere: in salads, in meat, in fish!”

Alexander Kahl pictured in front of the German Language Center in Yekaterinburg

Svetlana LomakinaThe German also categorically could not accept ‘herring under a fur coat’, one of the main Russian holiday salads.

At first, he also considered ‘okroshka’ a strange dish. “When I first tried it, I thought that the world has not yet invented anything worse: how could they pour lemonade over a salad?” And now, he can't live without it. “The main thing is to choose the right kvass, with sourness!”

The full version of the interview was published in Russian in the ‘Nation’ magazine.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox