The untranslatable word AVOS’ and why Russians rely on it

The word avos’ is impossible to translate into other languages - it has many shades of meaning and strong emotional connotations. It is always an expression of hope for success, even though the reasons for success are few. It is a hope and a trust in help from God and supernatural forces.

Avos’ can be both a particle and a noun. The particle avos’ means “maybe” and is used by people who say things in hope: “Avos’ I won’t be caught!” (“Who knows, I may not be caught!”; “maybe I won’t be caught!”; “I hope I won’t be caught!”). The noun avos’ also signifies hope (“To put your hope in avos'.”) - hope for a stroke of luck when there is little real chance of it.

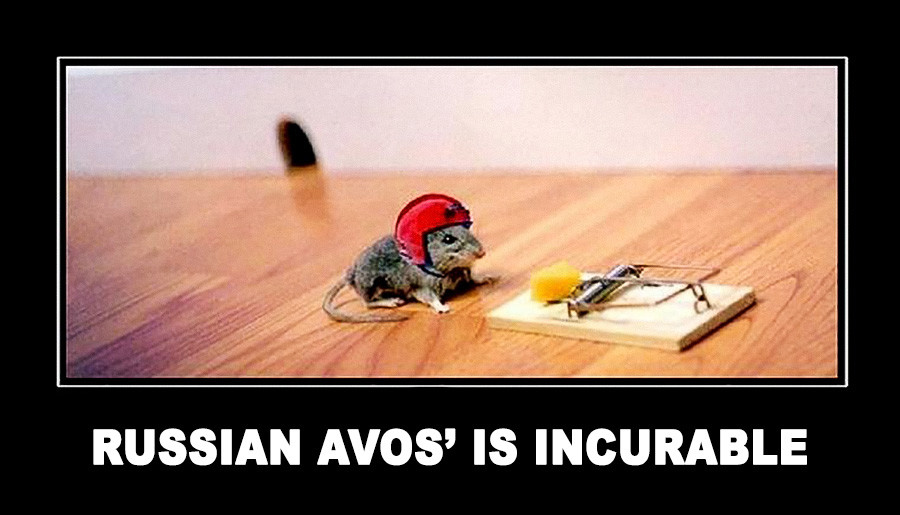

A student who hasn’t learned his subject still goes to the exam putting his hope in avos’. A criminal who is robbing a shop thinks, “Avos’ I won't get caught!”. A husband who has had a drink or two comes home, hoping that “avos’ the wife won’t notice”. Anglers walk on an ice-covered river in the spring, hoping that “avos’ the ice won’t break’.

The origins of the actual word were said to have been derived from "а во се" ("a-vo-sye", an outdated old Russian phrase meaning "but now").

The word was commonplace in the lives of the peasants. The Russian peasant used to do literally everything by putting his hope in avos’: He sowed a field hoping that “avos’ the seeds will sprout”; prepared for the winter hoping that “avos’ the food supplies will last”; gambled hoping that “avos’ I will be lucky”; and endlessly borrowed money hoping that “avos’ one day I’ll be able to pay it back”.

So why do Russians put their hope in avos’?

Avos’ always meant hope in God’s help. Russians are very superstitious, so you can’t just say “when the wheat sprouts”, because it might bring bad luck. But by adding avos’ you imply “God willing”.

The gentry also used the word. Here is Ivan Turgenev writing in a letter: “Avos’, God willing, I will leave here on Friday and, avos’, will come to see you on Saturday”. There are no insurmountable circumstances to prevent him from leaving on Friday and arriving at his destination on Saturday but he is, as it were, protecting his plans from the evil eye. It’s as if he is saying, “God willing, I’ll reach my destination,” or “God willing, I’ll be alive.”

By the way, the famous Soviet string shopping bag called avos’ka, that are famed for their practical and attractive design and are now back in fashion owing to the trend away from plastic bags. But ironically, people used to call them avos’kas in a jokey way. They used to take the bags to the market in the hope of procuring something. “Avos’-ka I’ll bring something back in it.” Soviet stand-up comedian Arkady Raikin, incredibly popular at one time, once said in one of his monologues. Russians simply like to court good luck.

Does avos’ work, though?

There are many proverbs with the word avos’ intended to wean a person away from having unfounded hope in unknown higher forces in the expectation that they will bring good luck at the right moment. “Hold on to avos’ while it is still there.” “Avos’ pokes even a fisherman in the ribs.” “On avos’ a Cossack gets on a horse and on avos’ the horse gives him a kick.” All this is also reflected in another pithy saying, still popular today: “Trust in God but rely on yourself.”

Russians don’t go to see a doctor for years because they believe that, avos’, it will get better by itself. Even Vladimir Putin, in an address to the nation, recently urged people to be responsible and said that, in the end, it is not worth relying on Russian avos’ in the context of the coronavirus pandemic.

But the most interesting thing about the Russian avos’ is that certain supernatural forces do indeed very often help! Thus unprepared students do pass exams in some miraculous way!

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox