Jessica's affair with St. Petersburg began 30 years ago. However, for the last three years, she has moved outside the city, choosing to now live in a country house.

She has connected her life with the Russian language and with translations. She’s worked on English-language TV in Russia as an announcer, voiced educational cartoons or messages for answering machines and sang in international bands in bars. She’s also translated books and catalogs into English for the Russian Museum.

Jessica is originally from Philadelphia. She first came to Russia in 1994 when she was just 16 years old. She had always wanted to travel and found an organization that could assist in funding a foreign trip for a child from a low-income family.

Jessica (top left) with her sisters, 1996

Personal archiveJessica applied and was surprised to learn that she was going to Russia.

She remembers her first impressions well. Everything in Russia was unfamiliar, everything was different. At that time, for example, there were no neon advertisements on the streets of St. Petersburg at all. And people did not know that paper towels existed.

On her first visit, the American spent three weeks in Russia. She learned the language and lived with an international group with 15 foreigners and 15 Russians. She liked it very much.

Jessica visited Russia again just shortly after she turned 18. Her parents were worried, but they let their daughter go across the ocean once more. And she ended up staying in Russia for a whole year.

It was the 1990s, a difficult time. “I understand that life was quite tough for the Russians back then, but everything was very interesting in this new world for me. I was exploring Russia.”

The American woman had about $2,000 for the year. And it was quite enough for her. For $100, Jessica rented an apartment and, with the rest, she spent on food: mostly potatoes and bread. Sometimes, she could even afford herself some ketchup.

On a concert of Yegor Letov with friends, the late 1990s

Personal archiveFor a whole year, the young American was just getting used to this new world. She read books and dictionaries. She walked the streets, rode the trams, listened to the local music and learned new words.

Her Russian friends often came to visit her, because she had a free apartment and they still lived with their parents.

“In St. Petersburg, it was more interesting for me to communicate with my peers: even very young people discussed philosophy, literature and touched on deep life topics. In the U.S., this is considered something personal: a question about God, for example. You can't just ask a stranger a question like that, unless you already know each other well.”

After a year in Russia, Jessica flew back to the U.S. and enrolled in the Department of International Relations at the University of Washington. Many of her fellow students got prestigious jobs immediately after graduation. Some in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, others on Wall Street.

Petersburg's American Jessica

Personal archiveBut, Jessica was not interested in that. Her soul was now in Russia. And her American friends did not understand her.

“One day, I realized that it was St. Petersburg that I missed. It happened on vacation, I had been living there for a long time and everything was fine with me. It was in India, when I was lying by the ocean, the weather was beautiful, the sun was shining and I suddenly realized I miss St. Petersburg's rain, the grayness, the canals!”

Jessica got married to a Russian named Pavel (the only time her parents visited Russia was for her wedding). And their daughter Mila is now 21 years old. Before giving birth, Jessica returned to the U.S. to be closer to her mother. But, when the daughter grew up, they returned to St. Petersburg.

“It was my conscious choice: I wanted my child to eat good food, to go to a good school. I'm not saying that all schools are bad in the U.S., by no means. But, where we lived, the school was failing.”

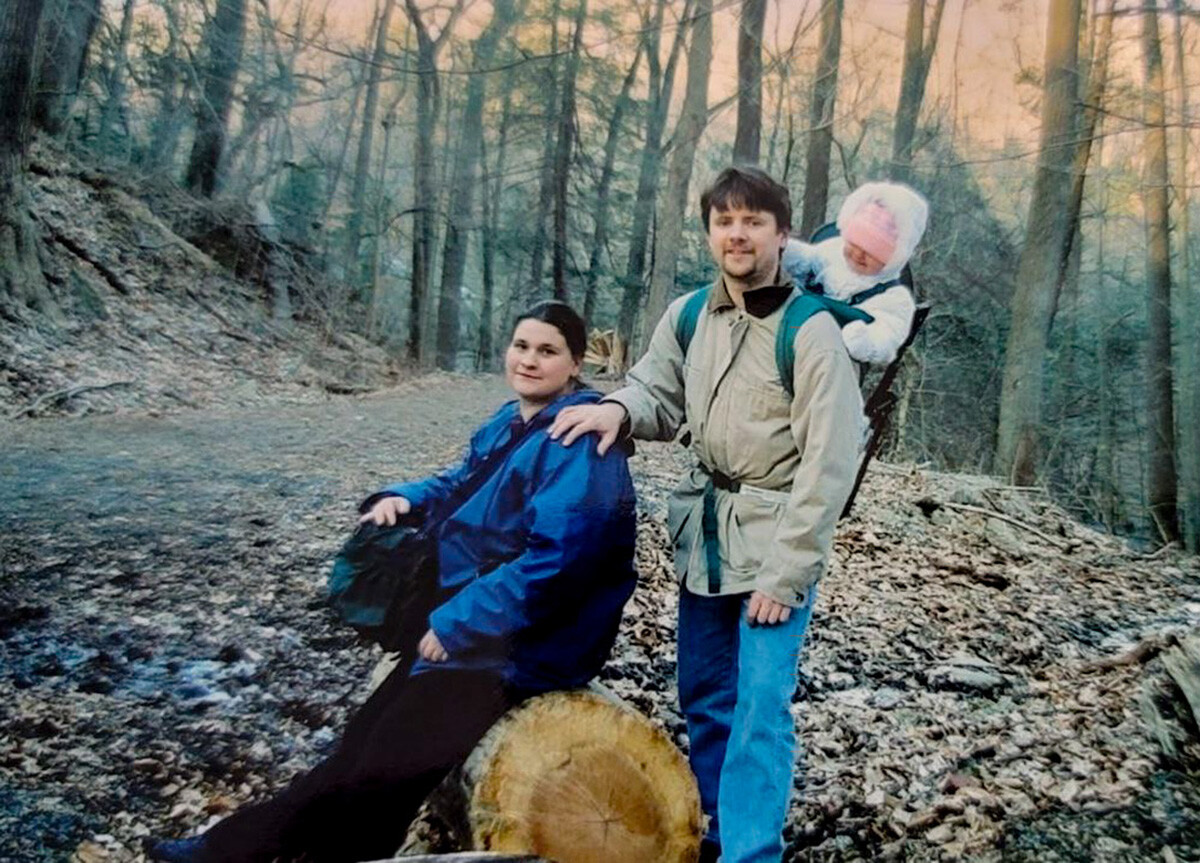

Jessica with her husband Pavel and daughter Mila

Personal archiveWith surprise, Jessica felt the difference in the upbringing of children in her homeland and Russia. “In St. Petersburg, for example, a strange old lady could come up to me on the street and say: 'It’s windy. Put a hat on your child, otherwise she could get sick and die!’”

Another surprise are parent-teacher meetings at school. “In the U.S., the teacher talks to the parent privately, but, in Russia, the teacher can reprimand your child in front of all the parents.”

Jessica's daughter has a U.S. passport, but she also stayed to live in Russia.

Jessica learned Russian with friends, including from songs by Viktor Tsoi and his rock band ‘Kino’. “When the tape ended, I would turn it and play it again.”

Jessica admits that when she speaks English and Russian, she becomes two different people. In Russian, she seems less nervous.

“I'm an introvert by nature, it's hard for me to find contact with people. In the U.S., I could afford to keep contact with strangers to a minimum, but, here, I was constantly in situations where I had to communicate. I had to get over my fears.

Singing in a bar

Personal archive“For example, when there were no supermarkets in Russia yet, you couldn't take a product and pay silently. You had to go up to a saleswoman and say, 'Give me half a kilo of macaroni, please.’

“If you didn't say it, you wouldn’t get it. I had no choice!” Jessica laughs.

In 2022, Jessica decided to move to the countryside.

“Life in the city is not changing for the better: cameras are everywhere, even goods can be paid for with your face. People walk around with their heads down, endlessly looking at gadgets, losing touch with the real world. And we have 30 people living in our village in winter and a hundred in summer. You walk down the street, say hello, stop to talk, everything is more humane.”

Jessica found a real village house and moved there and, soon, her Russian friend also moved in. Now, they have a joint household: two cows, two bulls, six goats, ten chickens and a rooster.

In a village with a neighbor

Personal archiveShe admits that, when in the city in a warm apartment all day sitting in front of a computer, sooner or later, you think: do I really live for this? But, in the countryside, such thoughts do not come, as there is no time for that.

“You have to stack firewood, bring water, and cook. Time takes on a different value and now I don't measure it by how much I can earn per hour.”

Jessica says the years in Russia have definitely changed her. “I can look at things much more broadly than other people. After all, I know life both there and here, so I see twice as much.”

The full version of the interview was published in Russian in the ‘Nation’ magazine.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox