Poet Lydia Pasternak steps out of the shadow

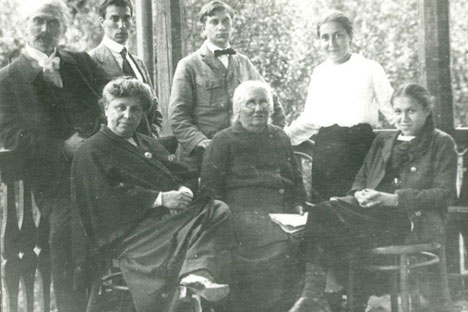

The family of Pasternak: Boris Pasternak is on the top second from left, Lydia is on the front right. Source: Press photo

Nicolas Pasternak Slater, nephew of celebrated Russian writer Boris Pasternak, is collaborating with the department of Slavonic studies at Vienna University to publish a trilingual edition of his mother’s poetry. Lydia Pasternak Slater has long been in the shadow of her famous brother, one of the most beloved poets of the 20th century and author of “Dr. Zhivago.” However her poetry allows her to stand alone in this celebrated literary family. Written in German, Russian, and English, her poems exhibit lyricism and range, encompassing witty pieces written for colleagues, as well as reflections on unhappy periods in her life. It also reflects her love for nature, a passion she shared with her brother, Boris.

The Pasternak family was split in 1921, when Boris’s parents and two sisters emigrated from the fledgling Soviet Union for Berlin. The family expected to be reunited, but the political situation and Boris’ determination to live and work in Russia ultimately made this impossible. Throughout this lifelong separation Boris Pasternak dedicated himself to his writing, driven by a fierce belief that his artistic vision was correct. His epic historical novel was smuggled out of the Soviet Union, and became an international sensation upon publication. He was forced to reject his Nobel Prize and faced condemnation and scorn within Soviet society until his death in 1960.

Nicolas Pasternak Slater is a retired hematologist who now lectures at literary festivals and conferences, as well as working as a translator. He grew up in a household where his absent uncle was a constant presence, a figure he felt he knew intimately despite never directly communicating with him.

His memories of the excitement when the family received a letter from abroad inspired him to translate and edit a collection of his uncle’s letters, published as “Boris Pasternak: Family Correspondence, 1921-1960.” This correspondence with his relatives was the closest Boris Pasternak kept to a diary, and offers an insight into the mind of a man sustained by an unshakable inner confidence.

RBTH: What originally prompted you to translate the correspondence between Boris Pasternak and his family?

Nicolas Pasternak Slater: I had particularly vivid memories of my childhood and the great excitement that was generated in the household on the rare occasions when a letter would come from Russia.

Just at the end of the war when I was seven years old, letters came which were smuggled through by English diplomats, and my mother would be very emotional about it. She would ring up her sister and they would discuss whether there were things left unsaid, and worry about whether anything awful had happened to the family.

RBTH: How aware were they of the reality of life for Boris?

NPS: He didn’t write about individual terrible things, writing in general terms such as “oh if you only knew everything, I can’t go on, I’d begin to howl.” They were aware that terrible things did happen, that people disappeared, that people were arrested and that these were things he couldn’t write about. So they were looking for hints and allusions, trying to unlock the code that he used. For instance when Vladimir Sillov was arrested and shot, Boris wrote that “he has died of the same illness as our late Liza’s husband, he thought too much and sometimes this leads to this kind of meningitis.” The family knew that the late Liza’s husband had been shot in 1918, and so this allusion to the ‘same illness’ was a clear indication of what had happened.

RBTH: How can these letters help us understand his character?

NPS: They show his enormous inner strength. He didn’t really depend on other people to provide him with support. He was very lonely, but he took great strength from a confidence that was he was doing was right. He believed in his poetry and later in the novel he was writing, and that compensated for absolutely everything. Even in the 1950s, when he was writing “Dr. Zhivago” and being persecuted and hounded, he wrote “don’t worry about me, I’m happy, I’ve probably never been happier.” He was satisfied that he was doing the right thing. He was an extraordinary person in that respect, for drawing inner strength and being supported by it.

RBTH: Can these letters help us shed any light “Dr. Zhivago?”

“Dr. Zhivago” is a story of the things that happened in Russia around the revolution and after. But it’s a story told from inside the people that it’s talking about. Above all he’s interested in the inner life of his characters, and the way that this sustains them. Boris believed passionately in life as a kind of force that was much stronger and much more interesting than external events. In one of his poems he writes “to be alive, that only matters, alive and burning to the end.” That really was the only thing that mattered to him; to be living your life in an honest and creative way.

RBTH: Are you tempted to produce a family translation of “Dr. Zhivago?”

Frankly not. First of all I think there are existing translations which are good, and I don’t think that I would be able to add anything just on the strength of being a family member. At the moment I’m working on a translation of my mother’s poetry, Boris’s sister. It’s difficult to publish because she wrote in three languages; Russian, German, and finally English. It’s going to result in a trilingual book, which I’m very much looking forward to.

RBTH: Tell us about her poetry.

Her poems are very personal, very much tied up with her own life, which was a rather unhappy and full of stories of unhappy love of one kind or another. There also very emotional, lyrical poems, about the landscape, about nature, about the sea. She was a very passionate person and she loved nature probably more than anything else. Her German poetry was written when she worked at a scientific institute in Munich. She was very popular with her colleagues, who were always celebrating something; birthdays, new arrivals, people leaving. Whatever event was about to happen, Lydia Pasternak got to write a celebratory poem about it for her friends. So these poems show her lighted-hearted side. They’re quite ironical, quite satirical, and quite fun to read.

RBTH: There was great excitement when “Dr. Zhivago” was published. What do you think about perceptions of Russian culture these days?

NPS: I think that the western perception of what’s going on in Russian culture now is at a low ebb. You very rarely read about current Russian writers and developments in Russian culture. That’s not to say that the interest isn’t there. I recently spoke at a Russian cultural weekend organized at Stonehill House in Oxfordshire, which had great feedback from attendees. I presented a film, which showed the extraordinary way in which public opinion was mobilized against Boris, with mass meetings of workers and intellectuals, who unanimously condemned Boris for producing this wicked slander on Soviet society. These people were obediently lifting their hands to condemn what was in the book, and of course none of them had ever read it.

RBTH: How is it that Pasternak suffered such public condemnation, but still escaped the Gulag?

NPS: Above and beyond everything else, Stalin was also a poet. His poetry is quite personal and lyrical. Maybe he had a kind of understanding of Boris as another poet who did not have a political agenda, who was only interested in things on a personal level. Maybe Stalin could see that in this way Boris wasn’t a threat. This wouldn’t have been the general view, because in soviet critical thinking, you’ve got to be engaged. Any attempt not to be politically engaged is itself more or less an act of political treachery. The establishment was solidly against him. Certainly at the time of the Zhivago affair that was what he was reproached with. Not so much that he wrote wicked slanders against soviet history, but that he was proudly aloof.

RBTH: Do you think that literature as a means of protest is diminishing, not only in Russia, but in society as a whole?

NPS: I don’t really believe that a work of literature is going to reshape Russian society, any more than it will reshape our own. Probably one reason is that we’re deluged with words in one context or another, either electronically or in newspapers.

These days, instead of one, great, monolithic protest, you have mass protest by millions of people on the Internet, which by its mass character also can be very effective. I think there will continue to be great works of literature which are protests, but probably a much more effective means of protest is mass communication devices such as Twitter.

For information on the autumn season of Russian cultural weekends, visit www.stonehillhouse.co.uk

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox