Bulgakov's diaries that go beyond 'A Young Doctor's Notebook'

John Hamm and Daniel Radcliffe (L-R) playing in the British comedic drama “A Young Doctor’s Notebook,” based on Mikhail Bulgakov's diaries. Source: Kinopoisk.ru

Mikhail Bulgakov has recently become deeply associated with the actors Daniel Radcliffe, John Hamm and the British TV show “A Young Doctor’s Notebook.”

The premiere of the four-part comedy drama brought Sky Arts one of its biggest audiences to date. All this came as something of a surprise in Russia, where the collection is nowhere near as popular as some of Bulgakov’s other works.

Like Anton Chekhov, Bulgakov was a doctor. He graduated from Kiev University medical school with distinction. Bulgakov took a job as the doctor for a clinic in Nikolskoe, a village about 200 miles (300 km) from Moscow.

But in those days, traveling to an emergency at night by troika through mounds of snow, it might as well have been 2,000 miles from the metropolis.

Semi-autobiographical medical stories, 1920s

Bulgakov’s semi-autobiographical stories from this period were printed in the 1920s in an obscure journal called Medical Worker. These stories were not known to the literary mainstream of the time.

The author was blacklisted by Soviet authorities, who had a special distaste for his work, especially the sad and hilarious novel, “The Heart of a Dog.”

The doctor stories were published together only in 1963, long after his death, and then not without the input of censors.

|

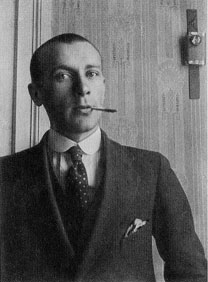

| Mikhail Bulgakov. Source: wikipedia |

The script for the TV drama, like the story collection, begins with a young, inexperienced doctor who goes to work in a village in the middle of nowhere. Immediately, he is called upon to extract teeth, supervise births and treat syphilis.

Radcliffe masterfully depicts the panic of the protagonist, who scurries from the patient in agony back to his room to consult his medical textbooks.

Other colorful storylines appear in the TV series: They include the doctor’s relationship with the nurse – the only vaguely young woman in the vicinity, and the hero’s hopeless addiction to morphine which leads to his demise.

While the TV version differs from the original story, we know that Bulgakov was intimate with addiction – and maybe this is why he is able to describe the seductiveness of morphine so powerfully.

However Bulgakov denied that he had been addicted to morphine and told his first wife Tatiana Lappa: “I am writing a story about a doctor who is ill. And since you are quite an impressionable person, as I see it, you will immediately assume the story is about me.”

“A Young Doctor’s Notebook” is not the only collection that draws heavily from Bulgakov’s life. Other lesser-known works offer small epiphanies about him.

“Notes on the Cuff” (1923)

“Notes on the Cuff” is drawn from Bulgakov’s professional life, and especially his experience of living on a writer’s salary in post-revolutionary chaos.

The work is fragmented, just as if it were written “off the cuff,” in this case. Part of the work was lost completely, and perhaps in part this gives the text its fragmented style.

Yet the fact that some things are left unsaid seems completely natural: The main character, ill with typhus, is delirious—and surrounded by mysterious events. Bulgakov also pokes fun at the Soviet authorities in charge of censorship – he had scores to settle with them.

The Soviet authorities reluctantly allowed some of his plays to premier on the stage, before finally banning them one by one. In a letter to the Russian writer and dramatist Maxim Gorky, Bulgakov wrote:

“All my plays are banned, there is not a single line of my prose printed anywhere, I have no whole work anywhere, not a penny of writer’s royalties and none likely to come any time soon, not one organization or person answers my petitions, in short – everything I have written in the Soviet Union over the past ten years has been destroyed. The only thing yet to be destroyed is me.”

“A Theatrical Novel”

Bulgakov considered “A Theatrical Novel,” his best work. It was written in his signature note-like style that is typical of Bulgakov – and again autobiographical in nature.

The narrator reads “notes of the dead” supposedly given to the writer by someone about to commit suicide, with the request that nothing be edited or changed. These notes, despite the fact that they were written ten years after “Notes on the Cuff” and “A Young Doctor’s Notebook,” portray similar explorations of despair.

The classically unhappy journalist in the novel writes for a maritime newspaper; he decides to quit his boring job to write a novel. The guests he invites to his house flatter and embrace him, eat and drink, but then tell him to his face that the novel is terrible and will never be printed.

Then they promise him that his novel will be staged at a theater instead, but deceive him. Sadly, Bulgakov had experienced each of these situations personally.

Joseph Stalin himself refused to approve Bulgakov’s play “Days of the Turbins” – a play based on the novel of one of his earliest autobiographical works, “The White Guard.”

It examines the toll the revolution has taken on the everyday life of the Turbin family. Readers feel the tumult as war encroaches on family life and the horrors of civil war unfold during an especially harsh winter in Kiev.

Blizzards are one of Bulgakov’s favorite motifs, and these storms make brutally effective appearances in “White Guard” and “A Young Doctor’s Notebook.” For Bulgakov, snow both accompanies and generates chaos and confusion.

In fact all of the trials that characterized his work - the civil war, unjust authorities, illness and despair—also characterized his life. What is truly moving is the sometimes funny, always terrifying beauty he made of it all.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox