Editor’s Note: Many readers know about Russians’ love for Leo Tolstoy during the reign of Alexander III — a rough-cut emperor who in his own way protected the literary and spiritual giant from exile. The people also genuinely loved John of Kronstadt, who lived a parallel life to the master of the modern novel. Millions believed in the priest, who was canonized, and revered him as a saint, even while he was still alive. Chekhov said that in every log house he visited in Sakhalin he had seen portraits of Father John hung next to the icons. Leo Tolstoy and St. John enjoyed the greatest rivalry of the age.

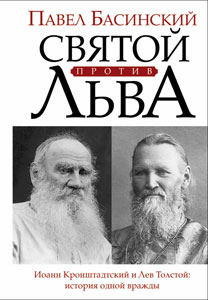

Pavel Basinky’s book “Saint versus Leo” was recently published in Russian by Elena Shubina Editorial of AST publishing house.

***

The memoirs of Ivan Zakhar’in, playwright and author appearing under the pseudonym Yakunin, chronicle a curious conversation. It arose between Russian Emperor Alexander III and the Countess Alexandra Andreyevna Tolstaya, the renowned Alexandrine, first cousin once removed of Leo Tolstoy, lady-in-waiting and governess of the Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna.

At the imperial court,Alexandrine had acquired a reputation for her impeccable piety, philanthropic leanings, exceptional intellect and literary taste, and for her independence of character, that most distinctive trait of the Tolstovian line.

The Emperor was able to reach the lady-in-waiting’s chambers via a separate elevated glass gallery connecting the Winter Palace with the Hermitage. One day, he paid her a visit to discuss the possible publication of Leo Tolstoy’s “The Kreutzer Sonata,” which had been banned by the Church censors.

“I allowed myself to express my support for the

Russian women often proved to be shrewder than the men. “The Kreutzer Sonata” was accepted for printing, but only as a part of a subsequent volume of the collected writings of Tolstoy. Even then, in 1891, these already attested to the writer’s huge appeal across the country.

“Tell me, who do you consider to be the most remarkable and popular persons in Russia?” the Emperor asked. “Knowing of your honesty, I am confident that you will tell me the truth. Do not

“I will not then.”

“Who would you suggest?”

“First of all, Leo Tolstoy…”

“As I expected. Who else?”

“One more

“Who, then?” the Emperor asked impatiently.

“Father John of Kronstadt.”

The Emperor guffawed and replied: “I can’t say he sprang to my mind, but I’ll go along with it.”

Zakhar’in did not witness this conversation, although shortly before the Countess’s death he was granted access to her archives, and from here and his own conversations with her he was able to piece together this episode. As a man of the

Laugh as he did, he also agreed. “In spite of the complete dissimilarity of these individuals, they had one thing in common: people of all classes came to them seeking advice.”

“And quite a number of foreigners would also come here with this aim,” the Countess recalled. “They would often visit me, imagining by dint of my surname that I could smooth their way to an audience with Leo Tolstoy. I usually told them that there was no need for my assistance as he welcomed everyone without exception.”

One might wonder if the celebrated archpriest, born Ivan Ilyich Sergeyev, the Abbot of St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Kronstadt, also received everyone who came to him, but that would have been quite impossible. For while dozens of people visited Tolstoy every day in Yasnaya Polyana, Father John [as he is known in English] was besieged by crowds of thousands, whether he was in Kronstadt, Samara, Vologda, Yaroslavl, or any of the Russian cities he visited on his numerous trips. If Leo Tolstoy had received as many people as arrived daily in Kronstadt, the trampling feet of the masses would not have left a single remaining sapling, bush, flower or blade of grass in his delightful Yasnaya Polyana.

Strictly speaking, Tolstaya should in her reply to the Emperor have mentioned Father John first and then her relative. But it is hard to imagine the Emperor’s reaction to such a

|

| “Saint versus Leo” by Pavel Pasinsky, AST 2013 |

The memoirs of the Countess feature a further interesting episode highlighting the Emperor’s relationship to “his” Tolstoy. In 1892, the London Daily Telegraph published a distorted translation of Tolstoy’s article “About Hunger,” which not even the specialist Russian journal Questions of Philosophy and Psychology was able to publish. The conservative newspaper Moskovskiye Vedomosti released excerptsof the piece in a reverse translation from English into Russian, even though the original text was at hand in Russia. Rather than expressing Tolstoy’s distress over starving peasants, these excerpts gave the impression that he was calling for the overthrow of the authorities, which precipitated a monstrous scandal.

Even the librarian from the Rumyantsev Museum, the philosopher Nikolai Fyodorov, refused to shake Tolstoy’s hand when they met, let alone the conservative strata of society. The office of the Interior Ministry was swamped with denunciations, and in accordance with the laws of the day, if he were to be subjected to a thorough investigation, Leo Tolstoy would at the very least be exiled to the remotest reaches of the Russian Empire. It was at this point that Countess Tolstaya rushed to her relative’s rescue, just as she had done on previous occasions.

“When I rode over to see the interior minister, Count Dmitry Andreyevich Tolstoy, I found him deep in thought,” she wrote. [Tolstaya is incorrect here, the interior minister at the time was Ivan Nikolaevich Durnovo, who was appointed to replace Dmitry Tolstoy after his death in 1889. She may be referring to a previous visit to Dmitry Tolstoy about a case involving Leo – PB.]

“I am really not sure what course to take,” he told the Countess. “Read these denunciations about Leo Nikolaevich Tolstoy. The first ones I put under wraps, but I cannot conceal the entire story from the Emperor.”

Alexander’s reaction exceeded the expectations of both the minister and the lady-in-waiting. “I ask you not to touch Leo Tolstoy; I have no intention of making a martyr of him and taking the resentment of the whole country upon myself,” he said. “If he is guilty, all the worse for him.”

“Dmitry Andreyevich came back from Gatchina in high spirits,” the Countess recollected, “because

Admonitions, but whose? “All of Russia’s?” Or the Emperor’s himself?

The minister’s report did not sit well with the Emperor, that much is certain. But however unfavorable he found it, the decision he made in response was favorable, the noble gesture of an enlightened aristocrat and not a Tsar. And Europe valued this.

“It was with such great joy,” recalled Countess Tolstaya, “that I began to inform in writing people all around Europe and across the ocean that Count Leo Tolstoy was living in peace at his home in Yasnaya Polyana and that our gracious Tsar had not even offered him a single reproach.”

However, when this gracious tsar lay on his deathbed in Livadia in October 1894, it was not Tolstoy who was summoned to his side, but Father John of Kronstadt; not the writer and philosopher, but the confessor and miracle-worker. It was not Tolstoy but John of Kronstadt who kept his hands above the tsar’s head and soothed his excruciating pain [he died of nephritis], and it was not the author of “The Kreutzer Sonata” who kept him company in his dying moments, but the author of “My Life in Christ.” And if by some miracle the Emperor had survived, there is no saying who would have assumed preeminence in his eyes as “the most remarkable man in Russia.”

But in October 1894, the Emperor had little to laugh about.

Fast-forward 14 years. In September 1908, the same confessor and miracle-worker who attempted to avert the Tsar’s death in the Crimea would enter in his diary his wish for a swift death for another sufferer. “Oh Lord, do not allow Leo Tolstoy, this heretic of all heretics, to survive until the Nativity of the Most Holy Mother of God, whom he has so terribly decried. Take him from the earth, this malodorous corpse, whose stench permeates everything worldly. Amen. 9 p.m.”

Tolstoy was seriously ill as he celebrated his 80th birthday, and so badly did his legs fail him that he had to be pushed out to his guests in a bath chair. There is documentary footage that shows the aged writer being wheeled onto the balcony of his house, sick but smiling and waving to reporters. The newspapers wrote endlessly about Tolstoy’s illness and John of Kronstadt certainly knew about it. But Tolstoy survived, and instead of

His body was transported on ice from the Gulf of Finland from Kronstadt to St. Petersburg with lavish, almost imperial honors. He was laid to rest in Ioannovsky Convent (which he founded), in a specially built white marble burial vault, complete with electrical lighting. No other priest in Russian history had ever been accorded such an honor.

People genuinely loved John of Kronstadt, millions believed in him and revered him as a saint, even while he was still alive. Chekhov said that in every log house he visited in Sakhalin he had seen portraits of Father John hung next to the icons. And as Russia lamented the death of the much-loved Tsar, Leo Tolstoy, who was also deeply fond of the Russian people, wrote in Yasnaya Polyana “how the man known as the Russian Emperor expressed his wish for the canonization of this great departed old fellow who had lived in Kronstadt. He also wanted the synod, i. e. that assembly which assumes the right to prescribe the only faith that should be observed by millions of people, to proclaim and celebrate nationwide the anniversary of the passing of this old fellow, and make his body an object of national worship.”

Two more years passed before Tolstoy in 1910 fled from Yasnaya Polyana to the monastery, first to Optina Pustyn and then to Shamoridino. He would have stayed in Shamoridino had it not been for a series of unfortunate and partly coincidental events. After his flight from

And so ends one of the most remarkable chapters of Russia’s religious and social history, which would later be dubbed “the fight of giants” by the future biographer of Father John of Kronstadt.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox