Cinematryoshka: Chechen War in the lens of young generation

| Press | to activate English subtitles |

After Turin graduated from the Ufa Petroleum University, he worked in his degree concentration on the oil fields of Siberia. Soon after, he truly understood that his heart lies in art: "The path to becoming a director is a long one; I’m not the first to come to directing with personal experience and education. Everything came together in a complex way. First, cinema was just a hobby while I was still at the petroleum institute. I made short films with an amateur camera and, only after some time had passed, I understood that this is the only thing I want to do."

Andrei Gelasimov, a theater director by education from Irkutsk, started his writing career in the 1990s with translations. In 2001, his first story, “Fox Mulder Looks Like A Pig”, was published and a year later, his story "Thirst" about young men returning from the Chechen War appeared (a sensitive issue in 2002). After this, all of Gelasimov’s books were met with huge success. At the Paris Book Fair in 2005, Andrei Gelasimov was acknowledged as the most popular Russian writer in France, surpassing Lyudmila Ulitskuya and Boris Akunin.

|

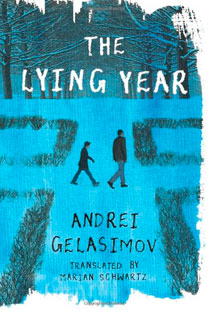

Review of the latest Gelasimov's book "The lying year" |

Andrei Gelasimov said at the press conference of the Kinotavr Film Festival this summer that the thing that irritates him the most in modern cinematography is “clichés of social drama.” He gave film director Andrei Zvyagintsev’s “Elena” as an example of cliché scenes and stereotypes. “There’s a poor family. The father doesn’t work, sits at home, and plays video games. A series of social clichés emerge: if a grown man sits at home, unemployed, and plays video games, then he’s an idiot. And I am supposed to not like this person.

Was the novice Turin able to avoid clichés in the big-screen version of “Thirst”? "I don’t think that we made some groundbreaking film or discovered a new language of cinema," - the director claims. "That wasn’t our task. However, we did use some techniques, like shots from a subjective camera. Our task was to tell the story of a man and how he came to the conscious desire to live. Some critics compare it to “The Belorussian Station” and other important films, but it’s hard for me myself to judge."

The life of Kostya (short for “Konstantin”), the main character, is split in two: before Chechnya and after. There’s very little that ties the recluse to the outside world. A veteran of the first Chechen campaign, he received a serious burn to his face in the war and an enduring resentment of life. Kostya completely shuts himself off from the external world, cutting ties to everyone around him, even his parents. Within the four walls of his house, he sips the last days of his life, mixing them with even harder drinks. Kostya fears the world outside his window, just as the world fears Kostya.

|

| Zachar Prilepin, special to RBTH |

"I don’t know if the attitude towards the Chechen War is changing in Russian society. Personally, it’s changing for me, says Gelasimov. "When I wrote “Thirst”, I was working at university and wrote about my students that were going to war at the time. But back then, I had the firm conviction that we should immediately end everything. I was a conscientious pacifist. But now, 10 years have passed, and I see what’s happening in Russia… We somehow presented ourselves in France with Zakhar Prilepin, but they gave us the cold shoulder because of Chechnya (both authors dedicated their works to the Chechen issue at the same time – editor’s note). Zakhar stood up to this and said, “You want us to apologize for Chechnya? That won’t happen!” And I raised my hand and said, “I agree. Excuse us, but the Caucasus will remain Russian." This sort of revolution has happened in my head over these years from the liberal intelligentsia to state “patriotism”.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.