Buratino or Pinocchio: The epic battle between Soviet and Western cartoons

'The Scarlet Flower' and 'Beauty and the Beast'

Kinopoisk.ruThe first cartoons appeared in Russia in the late 19th century, when Vladislav Starevich first invented stop-motion animation, whereupon the whole world began to observe the trials and tribulations of beetles living inside cardboard houses. Russian animation continued to develop primarily through Soyuzmultfilm, the studio that brought some of Russia’s

At roughly the same time as Soyuzmultfilm was founded in the 1930s, the great reformer of world cinema Sergei Eisenstein made the acquaintance of another recognized genius by the name of Walt Disney. The Soviet director remembered the encounter in an article entitled “Disney”.

“Disney’s animals, fish, and birds are wont to stretch and contract. <...> This cry of optimism could only be done in

During the Second World War, the great comforter became the great propagandist.

Almost simultaneously, in 1942, Disney released a grotesque fantasy about the misadventures of Donald Duck in the Third Reich.

While in 1941 Soviet animators produced the agitprop piece What Does Hitler Want? He wants to return the land to the landholders and the factories to the capitalists, of course. What he actually gets is also understandable – a speedy death impaled on a Soviet bayonet.

In peacetime, animation once more began to fulfill its edutainment mission. The game of cat and mouse, known to every child, was brought to the screen by the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studio in 1940.

Since then, the whole world has had its eyes glued to the love-hate (mostly hate) relationship

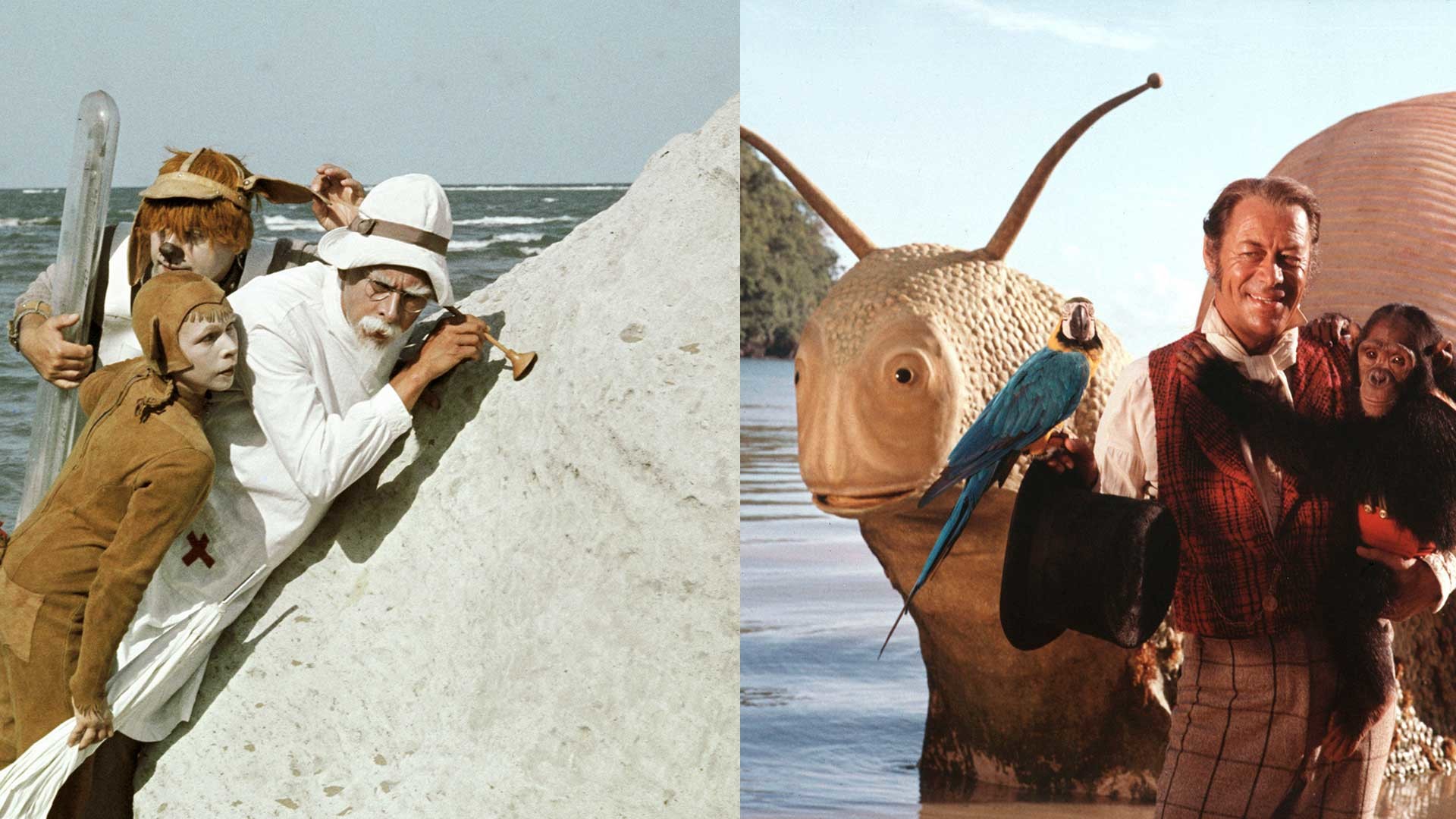

Soviet animation inspired and was inspired not only by Walt Disney Studios. For example, the English cartoon Doctor Dolittle (1971), based on the book by Hugh Lofting, influenced the Soviet Doctor Aybolit (1984), drawn (literally) from the tale by Korney Chukovsky.

Dr Aybolit VS Dr DoLittle

RIA Novosti / AFPAnother example is the Soviet Domovyonok Kuzya (1984), who is clearly a close relative of Pumukl (1982), who became a hero of German animated film.

Domovyonok Kuzya

Kinopoisk.ruAn undisputed success story of Soviet animation is the cartoon Winnie the Pooh and All, All, All. Who would have thought that Winnie the Pooh (1969) would end up capturing the hearts of Soviet audiences of all

Last but not least, let’s compare Disney's Beauty and the Beast (1991), based on the French fairy tale by Charles Perrault, and the Soviet cartoon The Scarlet Flower (1959), based on the fairy tale of the same name by Aksakov (1868), which drew heavily on Perrault’s work.

The assertion that different countries’ cartoons are alike is essentially a truism. The fairy tales of some countries do indeed resemble those of others, but fairy tales draw their ideas from mythology, which differs little in principle across the globe, from the tribes of Papua New

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox