Russia among top 3 global leaders in solar module production

The Kosh-Agachskaya solar power plant in the Republic of Altai.

Alexandr Kryazhev/RIA NovostiEven though demand for solar energy in Russia is low, the Moscow-based company, Hevel, is producing solar modules with an energy conversion efficiency of 22 percent, which is the world’s highest.

In addition to Hevel, only two other companies in the world produce solar equipment with similar efficiency: Panasonic (Japan), and Sun Power (U.S.). Most other major global manufacturers, including Chinese and Korean companies, which have the largest market share, convert solar energy into electricity only with an energy conversion efficiency that rarely exceeds 15 percent.

How many solar power plants in Russia?

Russia's share of solar energy production is a paltry 0.03 percent of the country's total, and to meet its electricity needs the country relies heavily on traditional energy sources with high conversion efficiency, such as gas, oil, hydro and nuclear. Nevertheless, in the past three years Russia has been rapidly developing solar energy.

Kosh-Agachskaya solar power plant in the Republic of Altai was opened in 2014.

Press photoIn 2014, Russia opened its first solar power plant, and the country has 12 today. Soon the 13th will be launched. These are power plants that are part of the national unified energy system. Four are located in the Orenburg Region, two in Bashkortostan, two in Altai, one in Khakassia, one in Astrakhan Region, one in Dagestan and one in the Belgorod Region. Each has a capacity of 1-40 MW.

Overall, however, the total capacity of these solar plants is 150 MW, which is a mere fraction of the 300 GW that’s produced globally.

Buribaeyvskaya solar plant in Bashkortostan.

Press photoRussia began building solar power plants not because it was in vogue, but because their increasing effectiveness made them profitable in regions that are very remote from traditional energy sources, and which at the same time have much sunshine. Even in some regions of Siberia the number of sunny days is almost 300 a year, despite the low daily temperatures.

In addition to the plants that are a part of Russia's unified energy system, there are also solar power plants that function autonomously. For example, the solar farm in the Siberian village of Menza (3,800 miles east of Moscow) provides energy for three remote settlements, and the autonomous solar power plant in the village of Yailyu in Altai (2,500 miles east of Moscow) is more favorable for local residents than the old diesel generator. There is also a small plant on the famous island of Valaam (646 miles north of Moscow), which provides energy for the monastery's greenhouses.

The solar power plant in Menza.

Press photoMost of these solar power plants – with the exception of the Crimean plants, the one in the Orenburg Region, the one in the Belgorod Region and the plants in Khakassia - were built by Hevel. And the two largest also use Hevel’s photovoltaic modules.

In the near future, Russia plans to use another 334 MW of solar power in the Orenburg, Saratov, Volgograd and Astrakhan regions, as well as in the Altai, Buryatia and Bashkortostan republics. By 2022, Hevel plans to build solar power plants with capacity of up to 1 GW.

'Less silicon means lower prices'

Extensive plans to build new plants are related to the fact that Hevel has learned to produce solar modules with an energy conversion efficiency of 22-22.4 percent. This has significantly increased the profitability of solar energy.

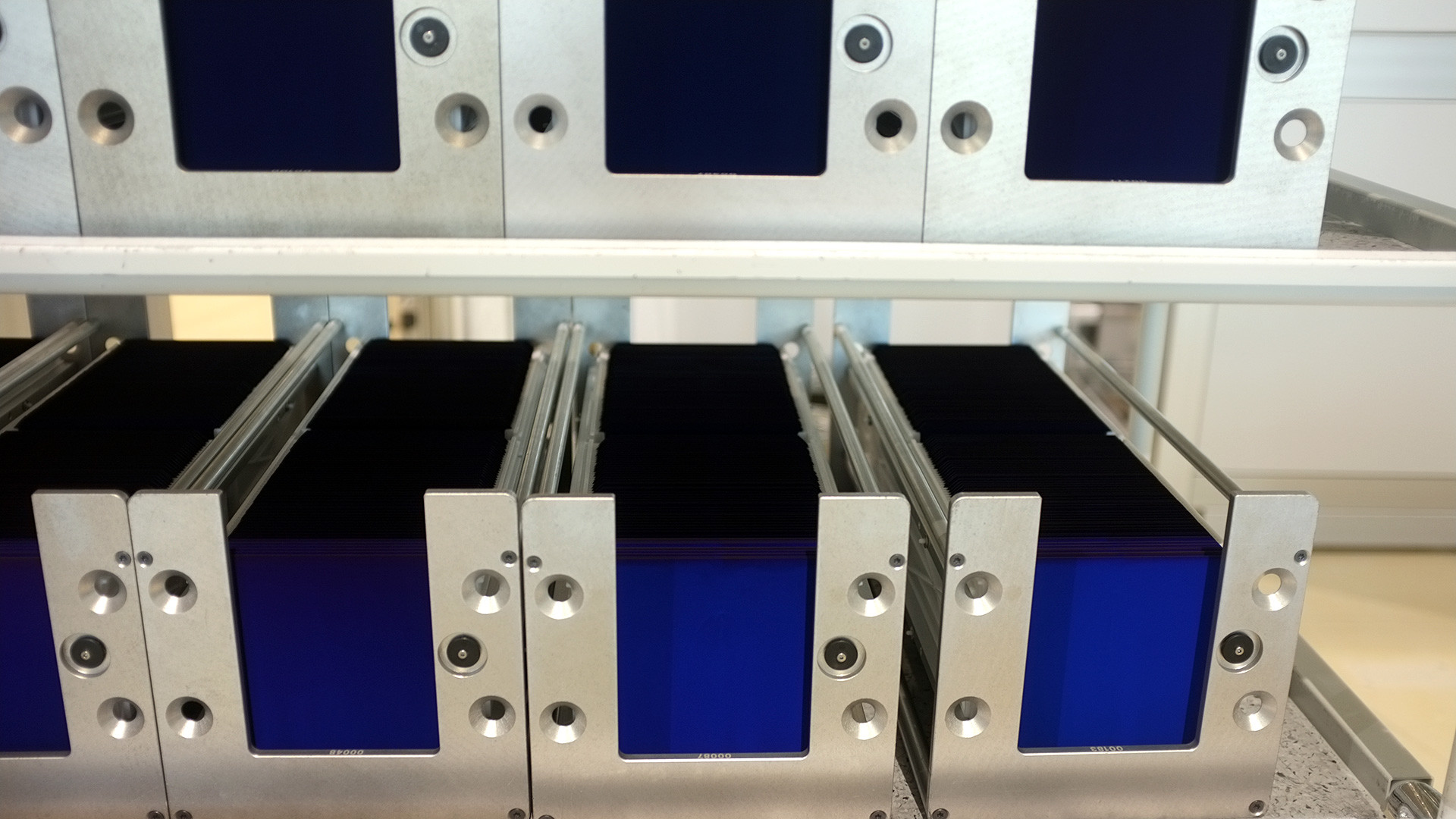

The new modules' energy conversion efficiency is more than 22%.

Anna SorokinaIn 2017, the company modernized its plant in Chuvashia with solar modules outfitted with heterostructured technology developed by a scientific research center in St. Petersburg. The average power capacity of these modules is 300 W, which is equal to two previous generation modules.

Furthermore, the new modules are more effective in cloudy weather, and they are also two-sided. According to Hevel's general director, Igor Shakhrai, the cells absorb light reflected from snow, water, sand or earth, and the lifetime is 25 years in a temperature range of -40 to 85 degrees Celsius.

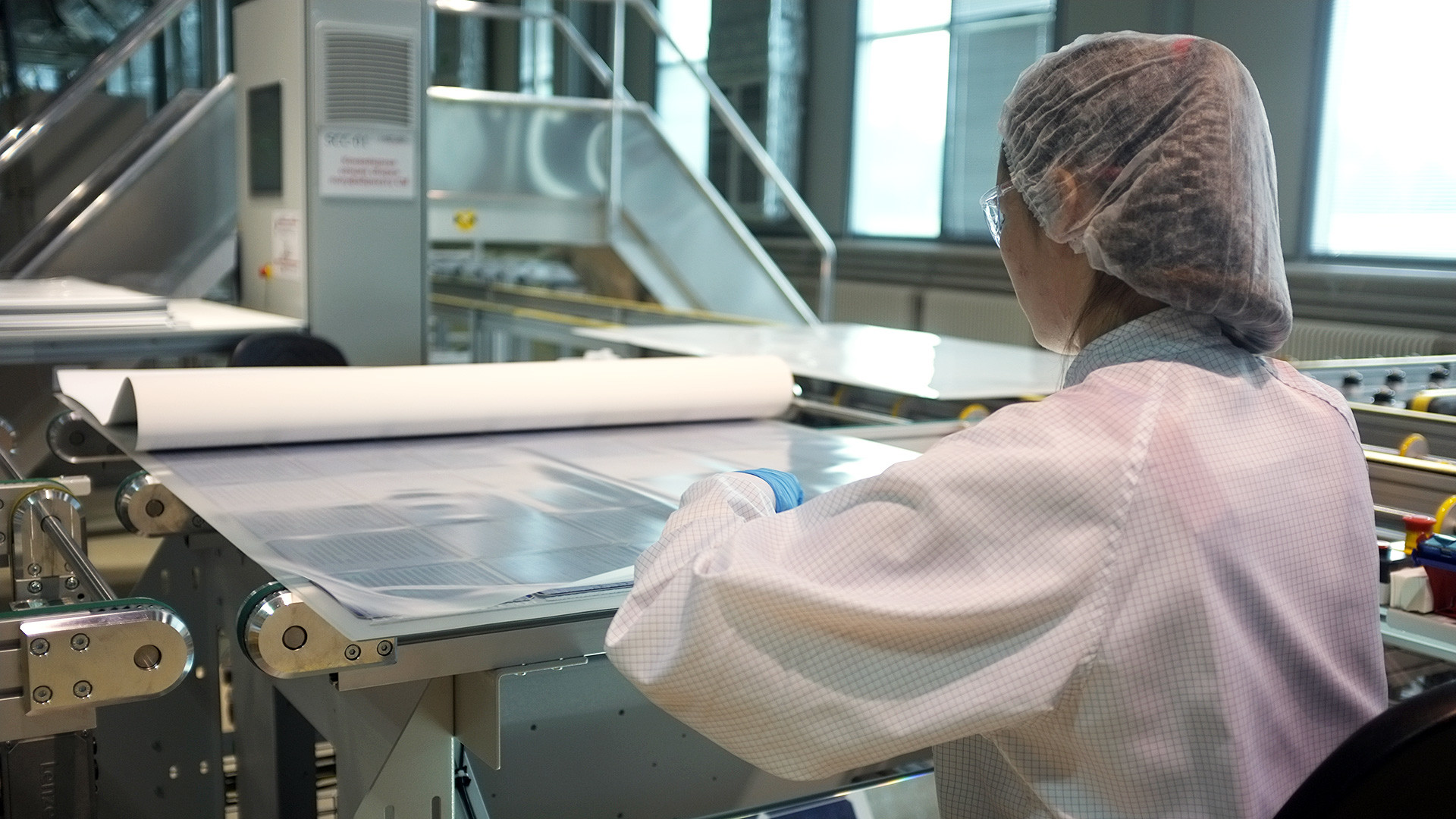

At the Hevel's plant in Novocheboksarsk, Chuvashia (430 miles east of Moscow).

Anna SorokinaThe cells themselves consist of mono-silicon plates whose surface is sprayed with nano-layers of amorphous silicon and then indium tin oxide (ITO). "This helps the future module cell to absorb the maximum quantity of light and then convert the light into electricity," said the plant's leasing engineer, Petr Ishmuratov.

Each plate is 180 microns thick, but there are plans to make plates with a thickness of 150 microns, and eventually even 90 microns. Why? The thinner the plate, the cheaper the module. "Less silicon means lower prices," Shakhrai pointed out.

Each cell is only 180 microns thick.

Anna SorokinaThe company has invested almost 4 billion rubles ($68 million) to modernize production, of which 300 million rubles ($5 million) came from the Industrial Development Foundation (IDF) created by the Russian government's Industry Ministry. The foundation partially covered the purchase, assembly and installation of the equipment.

"For now this is the first open IDF's project in the field of solar energy," said Roman Petrutsa, the foundation's director. Overall, there are 170 IDF's projects in the country with investment totaling 43 billion rubles ($750 million).

The first party of heterostructured modules was already sent to a new solar power plant in Altai. With a capacity of 20 MW, it will power about 4,000 homes and will be launched in September.

What about the consumer?

The construction of industrial solar power plants will help the company turn a profit within 15 years, according to Hevel’s press office.

The advantages of using solar energy are obvious: no damage to the environment, increased safety, and independence from fossil fuels. But can a homeowner save electricity and money if he installs a solar panel on his roof?

The solar plant on the island of Valaam provides energy for the monastery's greenhouses.

Press photo"Today, the demand for autonomous solar installations among consumers is growing," said Anton Usachev, director of the Association of Solar Energy of Russia. "In Russia the total capacity of such installations is about 6,000 KW, and the capacity of each is 5 KW. This is enough to provide electricity for home appliances: lighting, refrigerator, TV, etc. Basically, solar energy can be used for everything except heating."

Solar is most advantageous for consumers in Russia's South, Far East, south Siberia and in some central regions where traditional energy sources are distant and remote.

Some countries, such as Germany, have so-called "green tariffs," meaning that the consumer can sell his surplus to the national network. In Russia, however, residential homes use only autonomous solar installations. Yet, as Usachev explained, in 2018 Russia will develop the legal framework to facilitate the integration of homes with solar installations into the national network.

"Currently, market participants are preparing a proposal that will allow the consumer to sell his energy surplus to the network."

For this and other reasons, Usachev is beaming about Russia's solar future.

"Solar energy is gradually replacing traditional energy. Year after year, the costs of technologies and production are decreasing, while those of traditional energy do not."

If technology continues developing at this pace, in 10 years renewable energy will be more efficient than traditional ones. "Solar energy is the future," Usachev said.

Read more:

A sunny future in Russia: Developing alternative energy sources

Global energy: A long farewell to the hydrocarbon era

Russia joins the electric car race

Bio-fuel alchemy: Turning plant biomass into energy

How many EV-charging stations are there in Moscow?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox