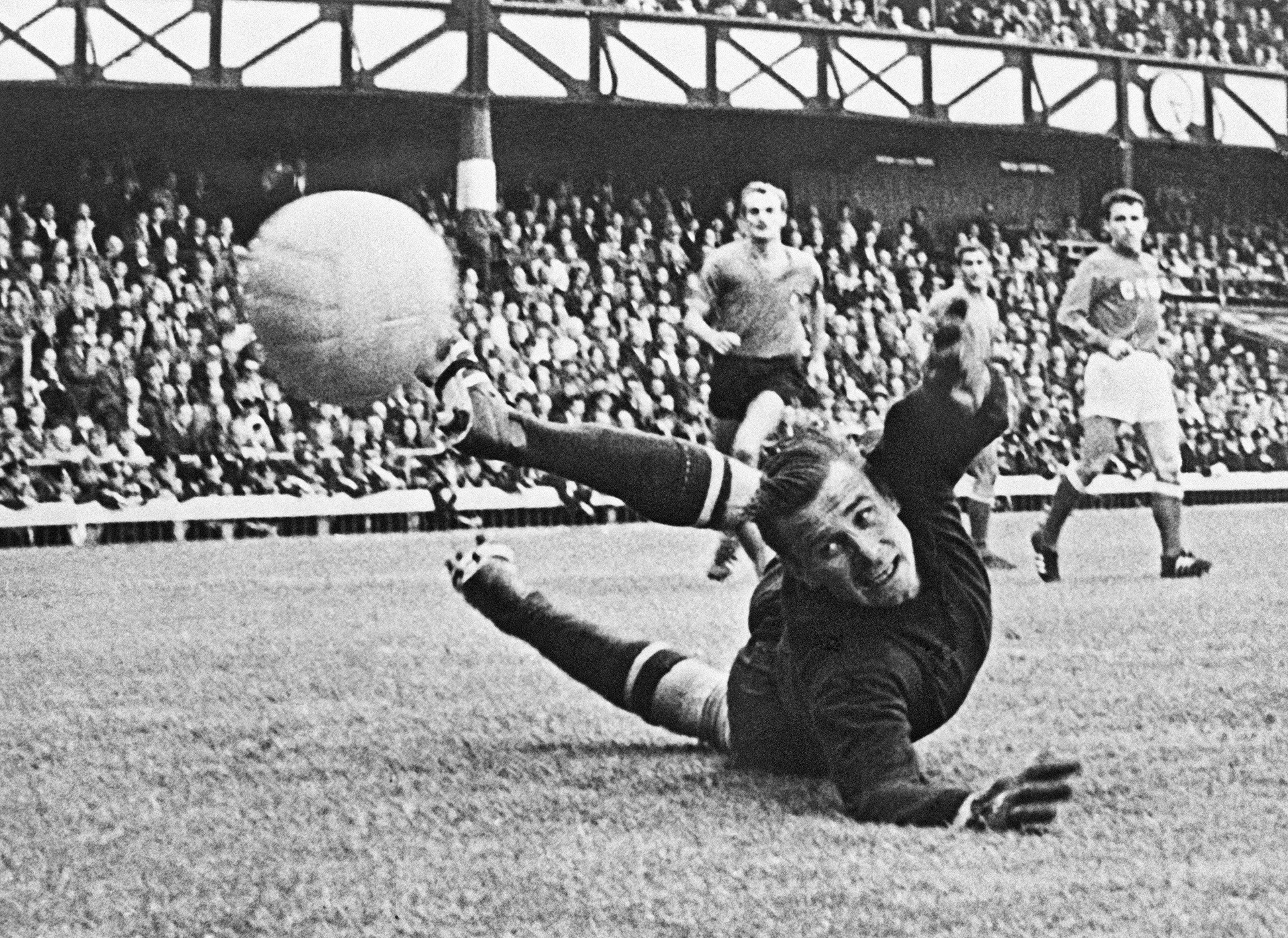

Lev Yashin (1929 - 1990), the best goalkeeper of the 20th century, portrayed during a play.

Viktor Shandrin/TASSIn football

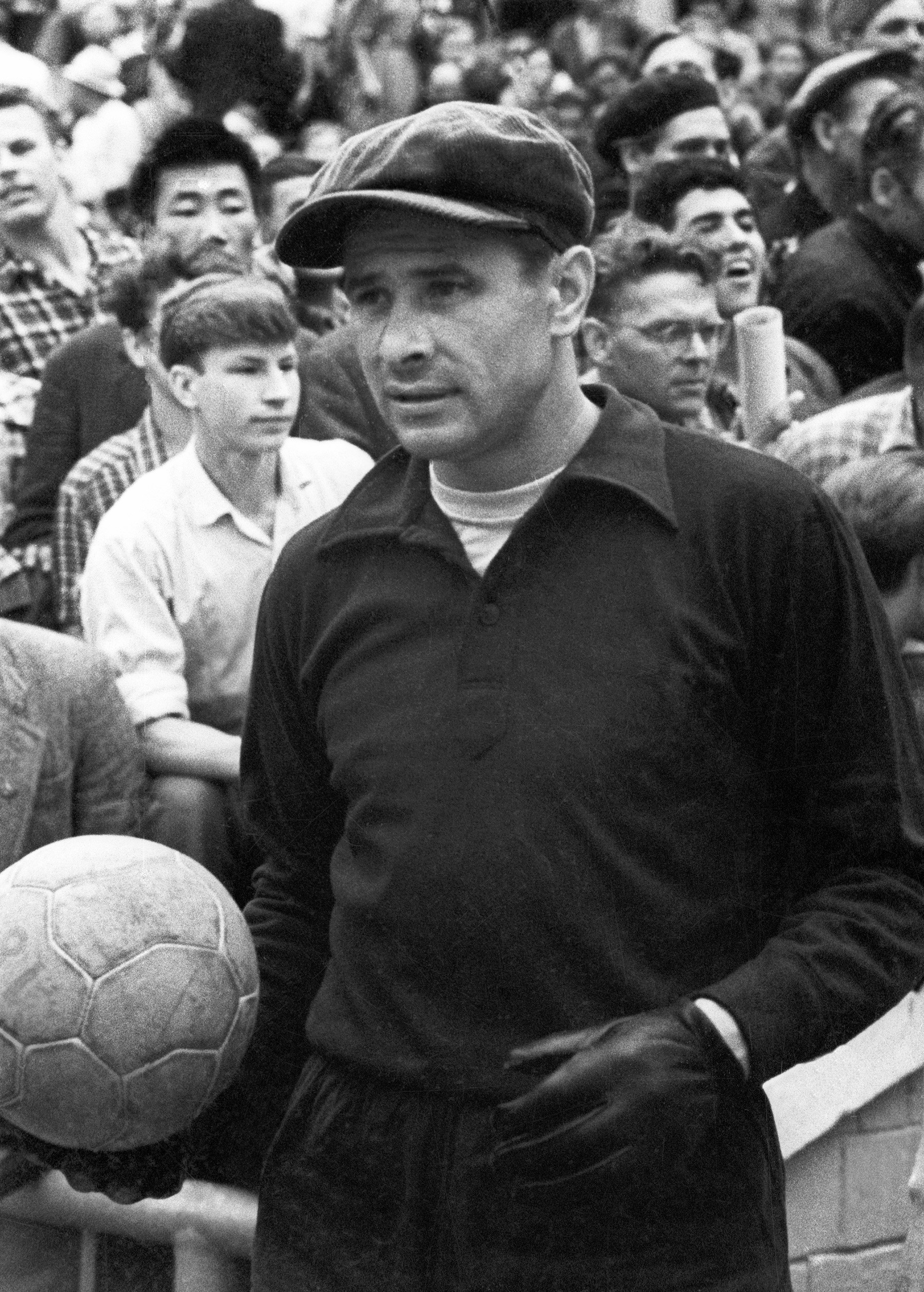

Yashin playing for Dynamo Moscow, his one and only club in the career.

Alexander Makarov/SputnikYashin had to earn it the hard way. Born into a family of a Moscow locksmith in 1929, the future legend was 11 when the war with Germany began – he worked unloading trains in Ulyanovsk (876 km east of Moscow) and then followed in his father’s footsteps as a locksmith.

Even after rising to fame while playing in international tournaments for the USSR, Yashin still thought of himself as a worker. “I need to touch the ball before a game just as a carpenter touches his wooden board before starting his work. It’s a working-class habit,” he once said in an interview.

Like many Soviet sportsmen, he didn’t enjoy the same salary compared to his European counterparts.

Nevertheless, Yashin never envied footballers playing from rich Western clubs, saying: “I couldn’t imagine living anywhere outside Russia.” He was incredibly loyal to his club – Dynamo Moscow – spending his whole professional career there, which lasted for 20 years (1950 – 1970).

However, it took the youngster from working districts several years to break into the senior squad. He became Dynamo’s number one keeper in 1953, going on to win five USSR championships and three USSR cups.

As his

Yashin was famous for his acrobatic skills and reaction, as well as changing the pattern of goalkeeper's play.

SputnikYashin was an innovator – he was one of the first “sweeper” goalkeepers. Nowadays, it’s normal – many goalkeepers, including Germany’s brilliant Manuel Neuer, play this way. Back in the

“Yashin, like many players whose game became a revelation for everyone, broke the common rules because they didn’t let him reveal his potential,” Mikhail Yakushin, Yashin’s first coach in Dynamo, wrote in his memoirs. “And it widened our team’s tactical potential.” The goalkeeper finished 160 of his 326 matches in the USSR championship with clean sheets.

In 1956 the Soviet national team won the Olympics in Melbourne, Australia, so they had a long return journey ahead of them: A ship to Vladivostok and then by train to Moscow, so that fans throughout Russia would have an opportunity to greet the champions. As team medic Oleg Belakovsky recalled, “On New Year’s Eve a bearded man came into a wagon with a bag, shouting: ‘Boys, where is Yashin?’ Lev came closer and this guy kneeled before him, taking a bottle of moonshine and a pack of sunflower seeds out of his bag: ‘It’s everything we have. Thank you – from all the Russian people!’”

With his hat and dark outfit, Yashin was an extremely stylish player back in the Soviet era.

Valentin Mastyukov/TASSYashin made sure he looked the part. Always dressed in a dark uniform from head to toe, he was nicknamed “Black Spider” for his flexibility and acrobatic skills. He also played in his iconic hat: “It’s my talisman, I always put it on,” he used to say.

Another, not so healthy part of Yashin’s image – cigarettes. “I’m a smoker, I know it’s a bad pattern to follow. I can smoke half of a pack in a day,” the goalkeeper confessed. Coaches tolerated it as Yashin’s habit did not appear to affect his performance. But it did damage his health and led to his leg being amputated due to artery damage in 1984. Six years later, he died.

The best goalkeepers, especially Russian ones, compare themselves to Yashin – and admit that his record is hard to surpass. “I’ll be happy if I can get to be anywhere near his level,” Igor Akinfeev, current number one of the Russian national team, said in November 2017, when Yashin appeared on the official poster of 2018 FIFA World Cup Russia™.

Not only Russia – the world remembers Yashin as well. He’s still included in all-star teams (FIFA 2018, for instance, has Yashin in its FUT ICONS team). Pelé, the Brazilian star who won three World Cups, still calls Yashin “forever number one.”

Nowadays, Russian national team is far from being on top – as it used to be in Yashin’s time. But this isn’t about bad players. Want to know the real reason? Read our article.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox