The noble struggle of 1812 has lessons for us today

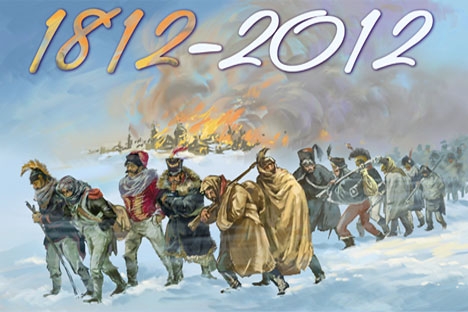

Drawing by Dmitry Divin

It was erected in June 1814 when Londoners enthusiastically greeted Russian Emperor Alexander I and his military commanders Field Marshal Barclay de Tolly and Cossack General Platov. Their visit marked the allied victory over Napoleon’s forces (though the final French defeat at Waterloo was still a year away).

The story began 200 years ago, when on June 24, 1812 Napoleon’s 600,000-strong Grand Armée crossed Russia’s western border. The 1812 campaign, named the Patriotic War by the Russians, is known to the British mainly through Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, which recounts how the seemingly invincible Corsican tasted defeat.

Related:

Nations united by ties of love, tragedy and friendship

Russian and British veterans celebrate together on Victory Day

Russia-UK: Why culture vultures can soar above political problems

Initially outnumbered by the French, the two Russian armies retreated, avoiding major battles. They eventually joined forces at Smolensk, where Field Marshal Kutuzov took command over the Russian forces. The bloodiest battle was fought on Sept. 7 at Borodino, a little more than 60 miles west of Moscow. The Russians consider it their victory although the Russian army had to retreat after a battle that was inconclusive in the military sense.

Tolstoy was right when he wrote that at Borodino “the Russians won a moral victory”. Both armies suffered crippling damage, two out of three casualties were killed by cannon fire, and Kutuzov let Napoleon enter Moscow, which was soon ravaged by fire. Meanwhile, the Russian army was gathering forces, the militia and guerrillas made life unbearable for the invaders, and in October Napoleon fled Moscow.

The rump of the Grand Armée was defeated in a series of engagements, the last of them being the disastrous crossing of the Berezina River. Before the end of the year, several thousand demoralized French soldiers were expelled from Russia, and in 1813 Alexander I led the European coalition to restore peace, stability and the balance of power in Europe, which was crucial for Russia’s development.

Thus, the road to Waterloo began at Borodino. Aside from diplomatic and military co-ordination of the war effort, we have a lot of other common legacies to celebrate. For example, Russia’s war minister and army commander Michael Barclay de Tolly, as his name suggests, came from a Scottish family. And the most magnificent monument of the war, the Military Gallery in the Winter Palace, comprising more than 300 images of Russian commanders of the period, was the work of the acclaimed British painter George Dawe. His work earned him more fame in Russia than in his native England. Portraits of Alexander I by British artists are also kept in Windsor and Apsley House.

It is especially significant to me that, here in London, I can shake hands with descendants of Russian soldiers and statesmen who won the crucial victory in 1812. One of them is Dominic Lieven, author of the brilliant Russia Against Napoleon and descendant of one of my predecessors, Prince Christopher von Lieven, who was in London between 1812 and 1834.

The 200-year anniversary of the war against Napoleon is a reminder that Russia and the United Kingdom were allies in 1812, confronting together common challenges, each doing its bit in the opposite extremes of the continent, and putting aside the mutual distrust, which was rife, like in some other periods of our history. Still, the leaders of 1812 were able to make the right decisions, prioritizing what was most important and what was secondary. We waged a just war to defend our countries’ sovereignty, not against the French nation but against the aggression personified by Napoleon.

Emperor Alexander I made an enormous effort to establish the Concert of Europe – which was the United Nations of its day – and urged Europe’s monarchs to treat their peoples and each other in a Christian way, for he believed that ties of brotherly love were stronger than coercion by force of arms or law. He also made a desperate attempt in 1812 to mediate between the then warring nations of Britain and the United States to ensure that the forces of important allies were not distracted by overseas conflicts.

Russia invested a lot in this principled foreign policy though the late 19th century was not an age of idealism. Thus, we saw the unnecessary Crimean War, which paved the way for German unification as a Greater Prussia and the countdown to the First World War.

Perhaps Britain should once more look at the lessons of 1812-1815, now that all of us in the Euro-Atlantic area share common threats and challenges. In a twist of history, we have been able to heal the discords with the French (as we did later with the Germans) and now Moscow and Paris enjoy a high degree of mutual trust and co-operation.

For Russia, the Patriotic War of 1812 was more than another armed conflict. It was an unprecedented cause of liberation for the whole of Europe, and it gave rise to a social and political awakening for Russian society. It shaped Russian patriotic sentiment and pride, and gave us a greater awareness of our Europeanness, of our national stakes in the peace and unity of Europe, which Fyodor Dostoevsky would later call “European nostalgia of the Russian soul”.

To commemorate the anniversary, our embassy, together with the Russian community in the UK and our British friends, has prepared a series of commemorative events. In a symbolic gesture, the first of them was the performance of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture with gunfire by HMS Belfast on Victory Day, May 9. In this way, the famous light cruiser, which led Arctic convoys in the Second World War when our nations struck an alliance again, resonated with much earlier common glory and sacrifice. I am sure the spirit of 1812 will live on.

Alexander Yakovenko is Ambassador of the Russian Federation to the United Kingdom. He was previously Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox