More dangerous world promotes Russia’s development

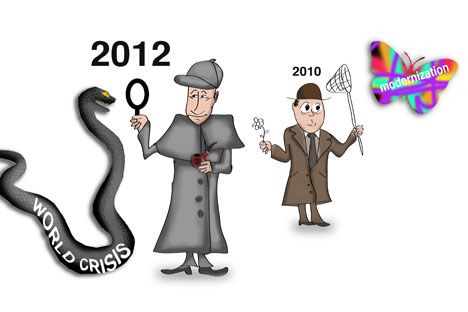

Drawing by Niyaz Karim

Former Russian President Dmitry Medvedev and current Russian President Vladimir Putin are close allies and like-minded people, as they have both repeatedly stressed. Yet a comparison of the speeches the men gave to Russian ambassadors and envoys – Medvedev’s in 2010 and Putin’s in 2012 – suggests that either the situation in the world has changed dramatically in the intervening period or that the two politicians see it from opposite angles.

Related:

Tough on foreign policy, soft on domestic

Putin confirms: Russia stands with Europe

“For all the sharp contradictions in the world arena, there is evidence today of a wish to harmonize relations, establish a dialogue and diminish conflict,” Medvedev said optimistically two years ago.

Yet last week Putin stated gloomily: “International relations are becoming ever more complicated… we cannot describe them as balanced and stable; on the contrary, the elements of tension and uncertainty are growing and confidence and openness are, unfortunately, not often in demand.”

Medvedev, 2010: “Spurred on by the international financial crisis, we are all looking together for new approaches to reforming not only the global financial and economic institutions, but the world order in general. We are talking, of course, about more fair collaboration principles, about building the relations between free nations on a firm foundation, on the firm principles of universal international law.”

Putin, 2012: “The world economy is afflicted by the metastases of crisis, and protectionism is becoming the norm… A significant number of our partners are seeking to ensure their own invulnerability while forgetting that, under present-day conditions, everything is interconnected. Nor does one see reliable ways to overcome the economic crisis… the outlook is becoming ever more alarming… The struggle for access to resources is intensifying, provoking anomalous fluctuations on the commodity and energy markets.”

This kind of contrasts are obvious throughout the speeches. Where the president in 2010 sees opportunities and prospects, the president in 2012 sees threats and cause for concern. Has the world really become so much more dangerous within such a short space of time? Or it is a difference of personal vision? It is both.

That the situation in the world is changing for the worse can hardly be denied. Since July 2010, when Medvedev visited the Russian Foreign Ministry, Europe has become mired in a debt crisis that keeps getting worse. The Arab Spring has brought mayhem to the entire Middle East, and the Iranian issue is becoming ever more acute. NATO has carried out another intervention to bring about a regime change. Afghanistan is still as far from peace as it was then; tension in Asia is growing and American politics are just as polarized. Yet all these trends were there before and, in 2010, Dmitry Medvedev’s radiant optimism surprised many, striking a note of discord with the opinions of most experts.

The difference lies in the point of departure. Medvedev proceeds from Russia’s internal development and looks for things in the external world that might promote this development. Putin, on the contrary, proceeds from the general picture of the world and draws conclusions as to how external events might influence internal Russian processes. To use a literary analogy, Putin uses Sherlock Holmes’s deductive method: on the basis of plentiful evidence, to reproduce the picture of the crime and, by contemplating it, conclude who is to blame. The evidence consists in the individual conflicts, crises and upheavals happening all over the place. The picture is one of an unstable, ungovernable, but aggressive and scary international environment that Putin described in a few touches in his Foreign Ministry speech and described earlier in detail in his election campaign article devoted to foreign policy. The criminals (or, to put it mildly, actors and agents) are the leading world powers, which, by their reckless actions, merely make the already very bad situation worse. “Those who are shooting and constantly launching missile strikes here and there, are great guys, and those who are warning of the need for a restrained dialogue are somehow culpable,” Putin said.

Putin’s trademark anti-Western attitude today has a very different character than did during his previous presidential term. At that time, it was aggressive: the West does not listen to Russia and does not want to take its interests into account, but we will make you listen to us and take those interests into consideration. Now, his skepticism has a touch of gloom and doom about it, as if he were saying: what are you doing? You are making things worse and worse... Not just in relation to Russia, but in general.

Putin keeps reminding the West that everything is interconnected and every action entails certain consequences. For example, recognizing the independence of a territory that is formally part of another state sets a precedent that will be repeated and forcible removal of a dictator triggers a chain of geopolitical shifts with unpredictable outcomes. The evidence creates a picture. The picture points to the culprit.

Although the Russian liberal constituency has dismissed Dmitry Medvedev as a like-minded person, a comparison of the two speeches shows that the third Russian president was a true liberal, at least as far as international relations are concerned. Like any liberal, he believes that external politics are determined by internal politics and must be geared to these. Most of the 2010 speech was a plea for modernization and innovation and for diplomats to be aware of all the basic principles of these processes. “We should decide which countries we should cooperate with to the greatest benefit of Russia’s development in terms of developing corresponding technologies and markets in order to bring domestic high-tech products on to the regional and global markets.” The second task, and remember that Medvedev here is still referring to foreign policy, is “to strengthen the institutions of Russian democracy and civil society. We should contribute to making social systems more humane everywhere in the world, and especially at home.”

This is an out-of-the-box approach. After all, from time immemorial, diplomacy has been grappling with one key issue, that of war and peace. The right answer to that question has always been the most tangible contribution by diplomats to the success of their country. Introducing the concepts of “democracy” and “humanization” into foreign policy discourse is a purely liberal approach.

Putin – as is particularly apparent by comparison with Medvedev – is a classical realist. To him, the structural factors, the international system that determines how states behave, come first. Sometimes it leaves no choice. Putin is concerned with the balance of power (which now also includes “soft” power), the country’s ability to be “self-reliant and independent,” i.e., not to sacrifice its sovereign rights. His speech, too, is sprinkled with references to markets and technologies (the word “modernization” is not used even once), but in a strictly applied, instrumental way. “Help our companies work more vigorously on foreign markets;” “do not be shy in promoting the products of the military-industrial complex;” to use the opportunities offered by the WTO, to abolish visas with the EU, to stimulate business… This is not a strategy. Putin simply does not believe it is possible in the modern world in principle. Instead, this is a tactic for expanding opportunities and building up strength because, without this, there is no chance of surviving in the modern environment.

There are other differences between President-2010 and President-2012. Medvedev, for example, tends to give priority to Asia and Putin to Europe. But these are details. One thing that President-2010 and President-2012 have in common is that they both know that Russia is an inalienable part of the world as a whole. “Russian foreign policy has nothing to do with isolationism or confrontation and it envisions integration into global processes.” The sentence sounds like Medvedev, but it is lifted out of Putin’s speech. One can see globalization as an opportunity, as Medvedev does, or as a threat, as Putin does, but there is nothing one can do about it. Herein lays the main cause of the continuity of the Russian foreign policy everyone is talking about.

Fyodor Lukyanov is Editor-in-Chief of the journal Russia in Global Affairs.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox