Russian artist in London: Visionary or cynical?

Works by Alexey Kallima. Source: courtesy of Regina Gallery

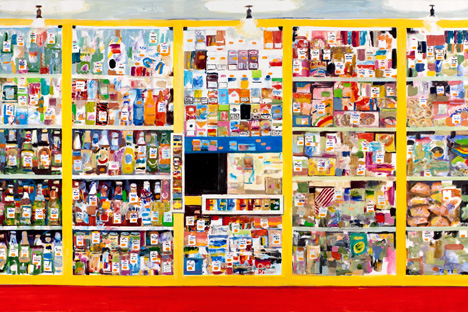

Chechen-born Alexey Kallima’s first solo show in London feels like a new departure. Where previous works have been heavily politicized and have used innovative media or a deliberately limited palette, “Everything is for Sale”is a series of bright paintings, naturalistically reproducing little Moscow shops so as to transform the gallery into a miniature market. The exhibition’s title suggests that these life-sized kiosks are a commentary on consumerism; but they are (perhaps with deliberate irony) perfect for sale in a commercial gallery.

In the late 1990s, Kallima worked with the performance art group, RADEK; in 2005, he created a 33-foot-long fresco in fluorescent paints, showing the Grozny football team, Terek, beating Roman Abramovich’s Chelsea. The picture vanishes in normal light and can only be viewed in the dark, reinforcing its subversive theme.

Related:

London celebrates Russian Art Week

Saatchi's collection of contemporary Russian art shocks, as usual

The 2008 series, the “Chechen Women's Parachute Team,” exhibited at Kallima’s first solo New York show, depicts crowds watching white parachutes falling from a blood-red sky or young women before or after the jump, echoing the heroic figures of socialist realism. As a refugee of the brutal war in Chechen, the themes of exile, heroism and resistance to the Russian state have been central to the artist’s prolific and widely exhibited work; Paris, Berlin, Barcelona, San Francisco, Perm and Kiev are just a few of the cities where his work has been shown.

Kallima (whose ethnically ambiguous assumed name is a type of butterfly) left Grozny for Moscow in 1995 and now lives and works in the Russian capital. His new series conjures up the details of life in his adopted hometown with uncanny verisimilitude. Large oils and watercolors depict the colorful contents of typical Russian kiosks: meat, fish, fruit and vegetables, books, clothes or vodka.

The displays of tins and packets are so realistic and evocative that anyone who has lived and shopped in Moscow is instantly transported back to the icy streets. The tiny window to keep in the warmth, which customers must bend down to speak through, is comically recognizable. An orange canvas depicting two green mobile services machines is a humorous addition to the exhibition – another ubiquitous feature of the typical street scene. There is also a nostalgic aspect to the paintings; “kioski” as retail outlets were among the earliest post-Soviet business ventures, but city authorities have recently regulated and demolished many of them.

Sometimes the labels are clearly legible; at other times, the indistinguishable rows of packaging take on an abstract quality, like a post-minimalist grid. There are also wall drawings in the artist’s characteristic fusion of charcoal and sanguine (red chalk); the technique recalls the age-old methods of artists like da Vinci or Rubens, but here it is used to depict a shelf of fashionable high-heel shoes or a contemporary watermelon-seller in a tracksuit jacket.

London’s Regina Gallery in Marylebone is a commercial gallery, with a branch in Moscow’s Vinzavod (also currently showing work by Kallima) and an active presence at international art fairs. The work on display in Moscow is radically different: a crowd scene called “Rain Theorem” is briefly illuminated to the sound of cheering as visitors enter. Vladimir and Regina Ovcharenko founded the Moscow gallery in 1990 and expanded with the Russian economy.

It is easy to see how these nostalgic slices of home would appeal to Regina’s Russian-expat client base in London. The paintings are visually attractive and engaging, drawing the viewer into the detail. Their size and price tags (roughly $16,254 for a large canvas) mean potential collectors need a suitably large wall and a healthy wallet. Tiba Fattori, the gallery manager, told RBTH that sales have been good.

So, is this mainly a moneymaking venture (artists must live somehow)? How does this exhibition fit Kallima’s reputation as a political painter – “the Russian Goya”? Visitors might find answers from the site-specific installation in the concrete-floor basement below the gallery. Downstairs, Kallima has created a “Stalactite Room,” and it is rubbish. The installation is literally trash: overflowing plastic sacks of newspaper, fast food packets and disposable coffee cups, all stuck to the ceiling of the dimly lit vault; but it is also disappointing as art.

Apart from the mild disorientation of turning the roof into a floor strewn with typical urban detritus and a clever sense of movement in the flyaway sheets of paper, the installation has little to recommend itself. Clearly, it is another comment on commercialism – but it is insubstantial, both materially and aesthetically. It might have been more convincing if the discarded wrappers came from the products painted upstairs. Apart from three, black, Russian cigarette packets, the trash is mundanely English, hastily assembled and installed. Kallima clearly believes that any old junk will pass for art in modern London, and he may have a point; in fact, that probably is the point.

The paintings are far more satisfyingly crafted, but, in some ways, more inscrutable. Tantalizing clues (the words “Ten letters” in various languages; the title “Art in Art” on one of the book stall’s volumes) seem designed to mock the search for meaning. The exhibition guide quotes Kallima’s friend and fellow artist, Valery Chtak, whose own London exhibition was called “Painting is a Dead Language.” Chtak insists that, in Kallima’s latest series, “there is no mystery … no moralism, no heroism, no bravado.” The simple goal, he explains, is to remove everyday things from their context and force the viewer to look more closely both at the painted images and at reality.

“Everything is for Sale” is open at the Regina Gallery in London through January 15, 2013.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox