Strengthening cultural ties between Russia and UK

Conan Doyle’s heroes are cast in their actual size. Source: Culture.ru.

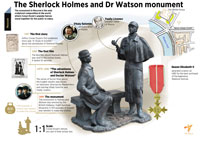

Its grand unveiling in 2007 was timed to coincide with the 120th anniversary of the release of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s first book about the ingenious detective, “A Study in Scarlet.”

The sculpture’s creator, Andrei Orlov, was inspired by the original illustrations of Sidney Paget, who first drew Holmes in his famous deer-hunter’s hat. Inspiration was also drawn from images of the Russian actors Vasily Livanov and Vitaly Solomin, who immortalized these characters in film.

Five Soviet films about Sherlock Holmes by the director Igor Maslennikov, made between 1979 and 1986, earned love and recognition not only in Russia but also in England. In 2006, the Queen of England, Her Majesty Elizabeth II, gave Vasily Livanov an order of the British Empire (OBE) for “the most convincing portrayal of Holmes in world cinema.”

In Russia, Conan Doyle’s famous pair has always been seen as the epitome of flawless English style – a look that deserved to be imitated. Their vital attributes were keen wit, a bright mind, a sophisticated sense of humor, self-deprecation, an aristocratic view of the world, straight morals, and an exquisite sense of style.

This is the classic image of an English gentleman that many people have tried to emulate.

What to do near the statue

1. If you need to make an important decision or solve a difficult problem, sit between the two sleuths and put your hand on Watson’s notebook. Be advised not to touch Sherlock Holmes’ pipe – this, according to Moscow superstition, will end in unpleasant consequences.

|

| Vasily Livanov (Sherlock Holmes). Source: Culture.ru |

2. Take a stroll along the embassy building and take in the minimalism of the architecture, designed by Richard Burton.

The main idea behind the statue is the proximity between Russian and English culture, which is expressed, for example, through the combination of traditional stones and environmentally-friendly wood materials used by English designers when they were building the interior.

The official opening on May 17, 2000, was attended by Princess Anne. Former prime minister of the UK, Tony Blair, said of the building: “It will not just be Britain’s window onto Eastern Europe; it will also be Russia’s window onto Britain.”

Anglo-Russian history

Cultural relations between Russia and England at the turn of the century gave rise to literary images and associations, but the two countries also held similar positions on a number of issues in world politics.

In 1698, when Peter I visited the British Isles, it marked the start of a new era in diplomatic and trade relations between the two countries. After a trade agreement in 1736, England and Russia fought together during the Seven Years’ War.

Relations cooled when Catherine the Great was on the throne, as she was skeptical of George’s “American campaign.”

Later, however, Russia and Britain joined forces to fight the French Revolution, and again in the war against Napoleon. All this released a wave of Anglo-mania in Russian diplomatic circles, and “everything British” became the latest craze in Petersburg.

At the beginning of the 19th century, a relationship of mutual sympathy and understanding was again tainted by suspicion. Alexander I had hardly returned from Europe, where he had been honored as the conqueror of the unconquerable Napoleon, when a bout of Russo-phobia broke out in London after Russian forces suppressed the Polish uprising of 1830-31.

Related:

Russia's underground art comes to London

Houston unveils monument to first cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin

Almost overnight, Russia seemed to take on the mantle of the number one enemy. Still, it was not long before a new common enemy appeared in the form of the Ottoman Empire.

When the Russian Imperial Ballet toured in London (a cultural event which served to cement a friendship between the two nations), any myths about the merciless barbarians threatening Europe from the East soon melted away.

Nicholas II’s tour of Europe with his wife Alexandra was crowned with a visit from Queen Victoria – Alexandra’s grandmother. Following the Anglo-Russian agreement of 1907, both powers became allies in the Triple Entente military and political alliance, which united them during World War I.

Russia and Britain remain key players and potential partners on the international stage. Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson, who now stand guard outside the British Embassy in Moscow, are proof of this, placing the friendship in its historical and cultural context.

Russian Anglophiles and Dandies

In the 19th century, European capital cities were gripped by a wave of Anglo-mania: it seems that St. Petersburg and Moscow were not immune from this trend.

In the years after 1840, Russians were not only traveling to England to read the fashionable works of Walter Scott and Dickens; people also went to the British Isles in droves on business and, more often than not, just for the pleasure it.

Upon their return from Britain, Russian counts Peter Shuvalov and Mikhail Vorontsov, along with the Golitsyn princes, established a number of parks in the English style, filled their estates with British colonial-style artifacts and made sure various important personages from England attended their soirees.

After Moscow’s German quarter burnt down in 1812, Anglican Church services were held in the house of the famous Anglophile Anna Golitsyna on Tverskaya Street.

In these same years, the upper-class youth, following in the footsteps of Pushkin, enjoyed making waves in high society by imitating the English dandies Byron and Вrummell.

Various eccentrics returned from fashionable London dressed in extravagant tailcoats and starched ties, turned down boots and with a new Russian speech littered with English words and phrases.

Some even went so far as to put on an English accent, pretending to be foreigners – something M. Pylyaev writes of in his book about the Russian aristocracy, “Wonderful Eccentrics and Originals.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox