5 facts about ‘Worker and Kolkhoz Woman’ – an incredibly troublesome Soviet statue

The Worker and Kolkhoz Woman sculpture, designed back in the 1930s, still is among iconic destinations of Moscow

Serguei Fomine/Global Look PressUnited they stand – a muscular man in overalls and a…well, muscular woman in a sundress, holding a hammer and a sickle in their hands. The Worker and Kolkhoz Woman monument

And, as well as actual workers and peasants of the USSR, this stainless steel couple have been through a lot:

1. Inspired by ancient heroes

The statue was created by Vera Mukhina, the master of socialist realistic sculpture, for the 1937 World Fair in Paris. It was the first time the Soviets were invited to such an event so the government (namely Joseph Stalin) was keen to make a big splash.

While working on the Soviet pavilion, which Worker and Kolkhoz Woman

The statue of 'the Tyrannicides' which inspired the creators of Worker and Kolkhoz Woman. Roman copy of the Athenian version.

WikipediaWorker and Kolkhoz Woman, in turn, should represent the socialist state emerging victorious over the whole planet. As Iofan would later write, the architectural ensemble itself was expected to be the main Soviet exhibit. And so it was.

2. Statue suspected to resemble Leon Trotsky

An almost anecdotic event occurred while Mukhina was working on the monument: A hostile engineer wrote to Stalin, trying to denunciate her, claiming that she had secretly depicted Leon Trotsky’s face somewhere in the gathers of the Kolkhoz Woman’s dress.

Absurd as it sounds, it was a serious claim back then. Stalin’s Great Purge was on the rise in 1937 so Mukhina could have faced serious trouble if this had been true. But it wasn’t. The officials examined the statue meticulously and found no traces of Stalin’s archenemy. Everything turned out fine.

3. Rivaled by the Third Reich monument

During Paris’ World Fair, the main struggle unfolded between the two future enemies of WWII: The USSR and Nazi Germany. The two monumental pavilions of the authoritarian states were placed directly opposite each other on the main pedestrian boulevard at the Trocadéro. It was a stare off!

Soviet and German pavilions facing each other directly during the 1937 World Fair in Paris.

Getty ImagesThe German pavilion, designed by the infamous Nazi architect Albert Speer, resembled a giant “III” (Third Reich) crowned by an eagle with a swastika. Symbols of Soviet Socialism and German Nazism were facing off, literally – a touch of French humor from the World Fair’s administration.

Some critics praised the monumental masterpiece of Mukhina and Iofan, but some were skeptical, calling it “faceless modernism.” Nevertheless, both Soviet and German pavilions won the grand

4. Placed where it did not belong

After the fair was over, Worker and Kolkhoz Woman went home. But a problem awaited: As they were separated from their gigantic pedestal in France, the Russian government had to find somewhere to place the 24.5-meter tall statue.

Firstly they considered erecting it at the Rybinsk Hydroelectric Station on the Volga River, then thought about Sparrow Hills (Vorobyovy Gory) in Moscow where it could be seen from basically the entire city. But these ideas didn’t work out.

A view of Worker and Kolkhoz Woman monument (front) by Vera Mukhina and Central Pavillion (background) from the side of Mira Avenue, 1959. Mukhina was very displeased with that view.

Valentin Sobolev and Vasily Yegorov/TASSIn 1939, during the opening of VDNKh (Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy) in the Russian capital, the statue was placed in front of

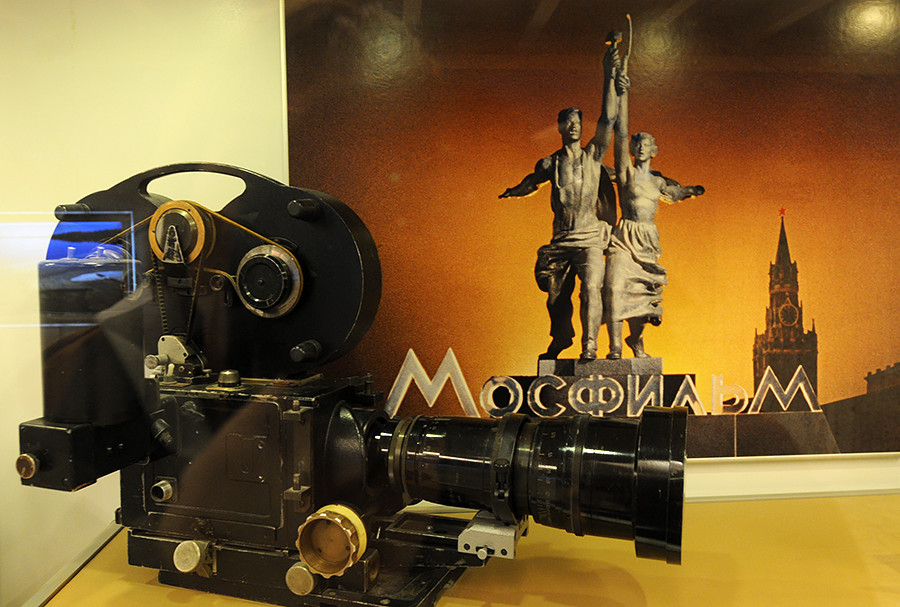

5. Became a cinema symbol and got a new pedestal

Though it hardly consoled Mukhina, her sculpture became an official emblem of the Mosfilm cinema studio in 1947. Since then every Soviet film made by this studio is introduced by a logo of a man and woman holding a hammer and sickle.

The emblem of Mosfilm cinema concern, picture taken in Mosfilm's museum.

Alexei Filippov/TASSIn 2003 the sculpture was cordoned off while repair works took place, and only in 2010 was it unveiled once again – and it finally got a higher pedestal (34.5 meters, 10 meters higher than the previous one), taking the total height to 58 meters: The fifth tallest statue in Russia. Now everyone can enjoy the beauty of this steel couple.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox