8 Russian books to help you find the meaning of life

In his book, Man's Search for Meaning, Auschwitz survivor and psychiatrist Viktor Frankl insists that a man can survive any form of suffering if he has

If you read any classic Russian novel of the 19th century then you'll certainly find characters who think much and are in search of their mission on Earth. Many find meaning in various kinds of service – to God, society or family.

1. Ivan Goncharov. Oblomov, 1859

Actor Oleg Tabakov (C) as Oblomov in Nikita Mikhalkov's film 'Oblomov' based on Ivan Goncharov's novel

TASSLaziness

The only strong and honest person in the novel who can love is Olga, the woman who managed to drag Oblomov out of his comfort zone. And that’s what he eventually says about love and his vision of life: “Poor angel! Why does she care for me so much? And why am I so fond of her? Better that we had never met! It's all Schtoltz’s fault. He shed love

2. Ivan Turgenev. Fathers and Sons, 1862

'Old Parents Visiting the Grave of Their Son,' 1874. The painting's plot was probably taken from Turgenev's novel

Vasily Perov/State Tretyakov GalleryTurgenev was the first to declare the eternal problem of fathers and sons: the elder generation will never understand the younger. The main issue on which their opinions diverge is a different view on the meaning of life.

The elder generation sees love, happiness, enjoying art and nature among life’s most important facets. Sons reject the “old world,” even reject love and want to devote themselves to something useful. The main character is the nihilist Bazarov who wants to become a doctor. He is ready to give up love to avoid becoming a slave of passion.

When his beloved, Anna Odintsova, asks what future he sees for himself and who he actually is, he only says that he's a doctor. He intentionally doesn’t discuss the greater purpose of life, because you don’t need “these abstractions”... to put a piece of bread into your mouth.”

3. Fyodor Dostoyevsky. The Brothers Karamazov, 1880

Actor Andrei Myagkov as Alyosha in Ivan Pyryev's movie 'The Brothers Karamazov'

SputnikWe recently wrote that this novel is one of the leading books about God in Russian literature. In fact, it seems this entire ‘looking-for-meaning’ quest started with Dostoyevsky. He and his St. Petersburg depression led him to reflect much about why and for what do people live. (He had much time in a Siberian prison camp to ponder these questions).

Brothers Alyosha (a monk) and Ivan (an atheist) argue about God and

“As soon as he [Alyosha] reflected seriously he was convinced of the existence of God and immortality, and at once he instinctively said to himself: ‘I want to live for immortality, and I will accept no compromise.’ In the same way, if he had decided that God and immortality did not exist, he would at once have become an atheist and a socialist.”

4. Leo Tolstoy. Resurrection, 1899

Actor Yevgeny Matveyev as Prince Nekhludov in Mikhail Schweitzer's movie 'Resurrection,' 1960, an adaptation of Tolstoy's novel

MosfilmTolstoy considered this particular novel to be his finest, and he became angry when people praised him only for War and Peace. The writer reflected and worked on it for more than ten years.

A woman was sentenced to a Siberian prison camp by mistake. A member of the jury, Prince Nekhlyudov saw all the

Here, Tolstoy defines one of his main ideas: Do not fight evil with evil.

“And it happened to Nekhludoff, as it often happens to men who are living a spiritual life. The thought that seemed strange at first and paradoxical or even to be only a joke, being confirmed more and more often by life’s experience, suddenly appeared as the simplest, truest certainty. In this way the idea that the only certain means of salvation from the terrible evil from which men were suffering was that they should always acknowledge themselves to be sinning against God, and therefore unable to punish or correct

5. Maxim Gorky. The Lower Depths, 1902

Actor Ivan Moskvin (R) as Luka and Margarita Savitskaya as Anna in Maxim Gorky's play 'The Lower Depths' staged by Konstantin Stanislavsky and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko at the Moscow Art Theater

SputnikA stranger, Luka, comes to a homeless

Only in the very lower depths can a person reveal

Another character, the rude Satin, is Luka’s opponent, and he sometimes tells lies for a good reason. Gorky wrote later that he wanted to raise the question of what’s better: the truth, or compassion and the white lie? What is needed more? A person should rise higher than pity, Gorky thought.

6. Andrei Platonov. The Foundation Pit, 1930

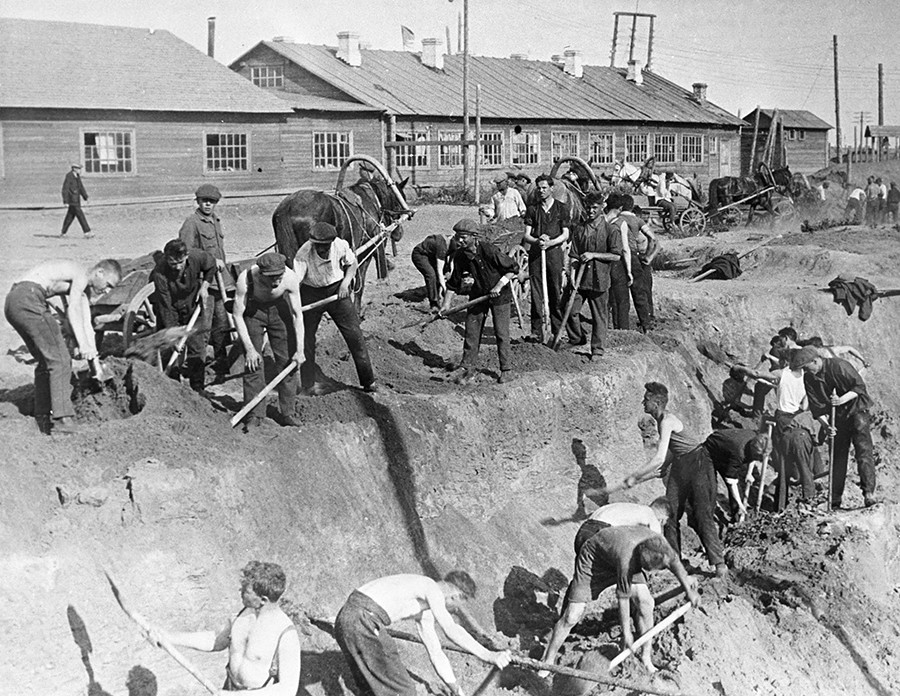

Builders at the Sharikopodshipnik plant digging in the ground, 1930s

SputnikThis dystopian story favors the pessimistic point of view, that nothing has any meaning. Working people are building a house for the happy proletarian future. Like

Platonov imitates the official Soviet language, and his characters even talk as if they sign those useless documents with exuberant formal vocabulary, even in speeches: “Here, however, rests the substance of creation and the aim and goal of every directive, a small person destined to become the universal element. That’s why it is essential we finish the foundation pit as soon as we can, so that the home may appear more quickly, and childhood personnel may be shielded from ill wind and ailment by a stone wall.”

Well, office plankton can probably learn from this.

7. Mikhail Bulgakov. The Master and Margarita, 1940

Mikhail Berlioz, Woland and Ivan Bezdomny, a screenshot from эThe Master and Margarita' series, 2005

Goskino, Telekanal RossiyaWhat if a book becomes the purpose of life? If a Master writes something that really matters for himself, then that can be a question of life and death; even when your Margarita signs a contract with the devil to let your book live. “Manuscripts don’t burn,” and characters are

As a result, the eternal powers decide the Master’s destiny, and his labor is rewarded with rest and eternal life.

“‘He [Jesus] has read the master's writings,’ said Matthew the Levite, ‘and asks you to take the master with you and reward him by granting him peace. Would that be hard for you to do,

8. Venedict Yerofeyev. Moscow – Petushki (a.k.a. Moscow to the End of the Line), 1970

'Moscow-Petushki' performance staged by Chelyabinsk Maneken theater

Alexander SapozhnikovIn this cruel world there is no place for the main character, Venichka, and his soul, pure like a newborn. Critics see Venichka as traveling in the

“For isn't the life of man a momentary giddiness of the soul? And an eclipse of the soul as well? We are all as if drunk, only everybody in his own way: one person has drunk more, the next less.”

Despite what everyone usually thinks, this novel (or poem, as the author defined it) is not about alcohol consumption. It’s about protesting social rules.

There is a passage that clearly refers to Jesus Christ: “Man should not be lonely – that’s my opinion.

Not sure which Russian books to read? There's so much choice. This quiz will help you figure out which novels best suit your interests.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox