How the Soviet avant-garde made sex and death fashionable

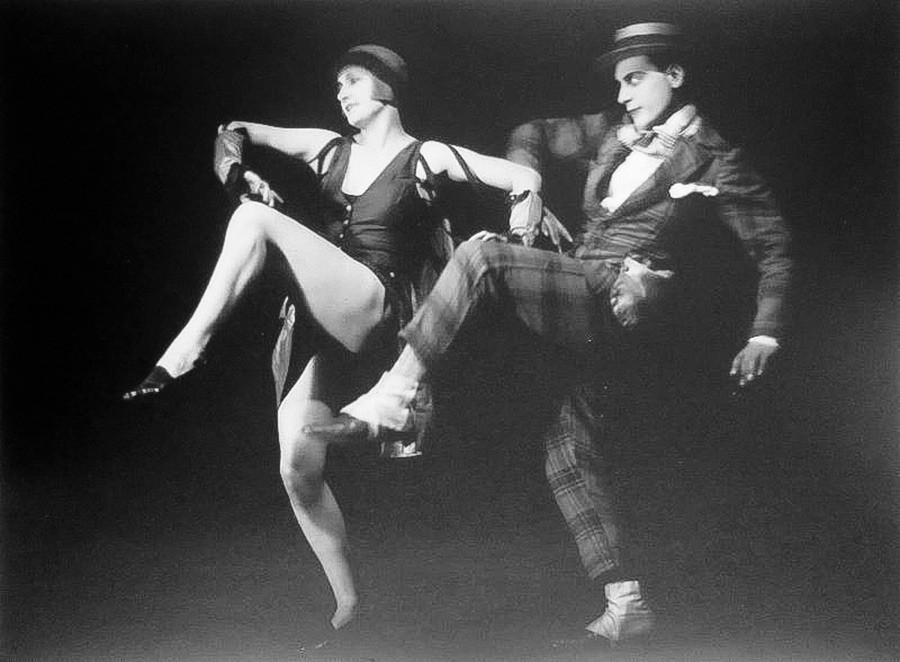

The epoch that follows any tremendous upheaval invariably delivers nothing but disappointment and shattered illusions. 1920s post-revolutionary Russia, according to Dmitry Bykov, was no exception. The first interwar decade produced no new genres or heroes, but merely reaped the fruits of the Silver Age in Russian poetry and the avant-garde in art. After the austerity of “war communism,” the New Economic Policy (NEP) promised an easing of economic hardships, and with it a headlong plunge into debauchery.

“In marriage and sexual relations, a revolution is approaching, in harmony with the proletarian one,” the famous German Marxist Clara Zetkin recalled Vladimir Lenin’s words. Yet the sad truth is that the sexual revolution happened instead of—not together with—its proletarian counterpart.

Marriage in the USSR: The foundation of society or the satisfaction of instincts?

During the revolutionary period, marital relations “arose as a by-product, to satisfy a purely biological need,” wrote the revolutionary and diplomat Alexandra Kollontai. Moreover, both sides of the process were supposedly keen to take care of this requirement as quickly as possible to prevent it from interfering with the main business of "working for the revolution."

NEP also failed to restore the traditional family. On the contrary, Bykov writes that “sexual needs were satisfied without prudishness.”

Later, however, the Soviet elite proved to be more puritan. People's Commissar for Education Anatoly Lunacharsky wrote that “... in our society, the only correct form of family is one based on the traditional couple,” and Leon Trotsky argued that the party should be the guardian of moral purity.

Where does free love lead?

Ideas of free love became fashionable and a symbol of the era. Sexual appetite was equated to hunger, which people satisfy without any pangs of conscience or moral handwringing. Love threw off its romantic veil, modesty, and courtship rituals.

Alexei Tolstoy, for instance, in his story The Viper (1928), describes a sign of the times as being the ease with which basic needs could be satisfied. The assistant manager of the trust where the female protagonist works takes her to one side and says that “Sexual desire is a real fact and a natural need.” He proposes ditching the romance and proceeds to embrace her vigorously. She, however, resists.

In practice, free love turned into a series of scandals and disappointments. Men were not prepared for the fact that women themselves would start to choose partners, and women for their part were offended by the lack of courtship

L-R: Osip and Lilya Brik, Vladimir Mayakovsky

Lara Simonova family archive/russiainphoto.ruDepravity and boredom

Early satiety leads to boredom, loneliness, and taking risks with one's own life, asserts Dmitry Bykov. After everything has been tried at an early age, death is perceived as the only acute sensation left to experience.

Gleb Alexeev's The Case of the Corpse is written in the form of a diary kept by a girl named Shura Golubeva, who commits suicide because of unrequited love. But the story is about neither love nor death, but about boredom and cultural emptiness. Shura kills herself not because she is in love, but because she has nothing else to do.

“In this sense, post-revolutionary Russian life turned out to be considerably worse than the pre-revolutionary one it replaced,” writes Bykov. Students at the turn of the century had high hopes and revolutionary aspirations, but the "red" students of the 1920s or factory workers could only shoot themselves: “They had already tried everything else, plus there were still enough weapons to go round.”

In his story The Flood (1929), Evgeny Zamyatin speaks of the total loss of the individual. Along with erotic insanity and a suicide epidemic, one of the hallmarks of the late NEP period was

Bykov believes that two phrases of Zamyatin encapsulate the atmosphere of the era: “All night from the coastal side, the wind battered the window, the glass rattled, and the water in the Neva swelled. And all the while blood was

Read more: How the Russian Avant-Garde came to serve the Revolution

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox