16 delightfully bizarre Russian artworks

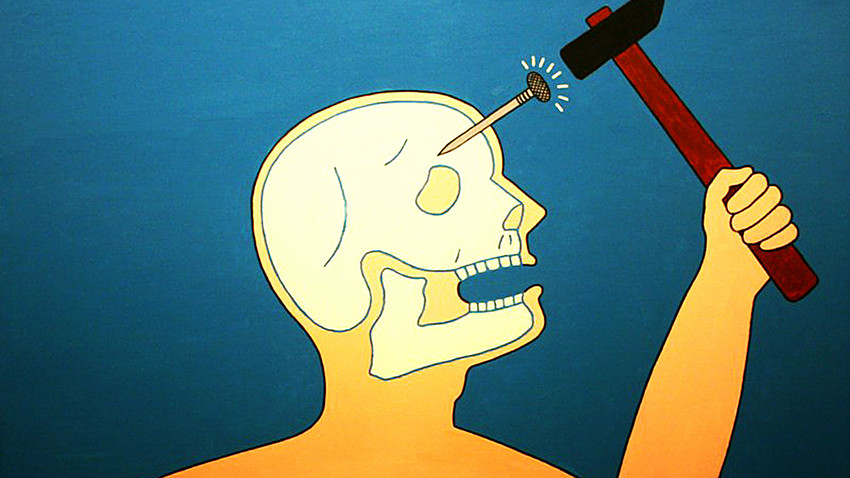

"The Knock Researcher" by Alexey Kozin and Oleg Maslov

Alexey Kozin, Oleg MaslovVK, the most popular Russian social network, is full of interesting pages bearing content that ranges from erotica to highbrow scientific articles. One such page, “Soviet-style Psychedelia,” contains avant-garde and underground paintings by Soviet and post-Soviet artists. Almost every single one looks absolutely cuckoo to the unprepared viewer.

You don’t need to know Russian to enjoy this extreme art: just follow the link above and scroll. For those who want to understand what this all is about, we selected our most-loved paintings and added short comments.

“The Movement of Thought”, Alexander Klimov (1999). Klimov specializes in so-called science fiction painting and his works touch upon the Universe, space

“

“The Knock Researcher”, Alexey Kozin and Oleg Maslov (1987). Painters from Leningrad, Kozin

“I Wave You Hello, My Second Self!”, Viktor Pivovarov (1999). Pivovarov was among the founders of Soviet conceptual art, where ideas take precedence over aesthetics. As you can see.

“Dangerous”, Erik Bulatov (1972-1973). Perhaps the most famous contemporary Russian artist, Bulatov mixes realistic sceneries with textual messages, which creates strange impressions. In this painting he transformed a picturesque Russian landscape into something more menacing by writing “DANGEROUS” on it.

“Your Time’s Up”, Alexander Dzhikiya (1989). Dzhikiya also combines painting with text but his work reminds one more of surrealistic and absurd dreams.

“Searching for History”, Alexander Kosolapov (1982). Those Soviet-era artists who were fed up with Communist ideology tried to deconstruct and mock it. In this work, Lenin gives scripts of wisdom to the Egyptian gods.

“The Sleeper”, Vasily Shulzhenko (year unknown). One of the gloomiest Russian painters, Shulzhenko portrays dying villages and depressing industrial zones of the former USSR.

“When the TV Screen Goes Black”, Georgy Kichigin (1991). When you turn the TV off, the only thing left is a black mirror where you see yourself lonely. The same idea gave Charlie Brooker inspiration for the popular Black Mirror series, but a Russian painter from Siberia thought of it decades earlier.

“Room 22”, Viktor Pivovarov (1992 - 1995). The text goes: “At night, she was turning into a beast, roaring terribly behind the wall and scratched with her claws.”

“Luck”, Damir Muratov (2005). Muratov, a painter from Siberia, claims to search for inspiration in the dumps of Omsk (a city 2,700 km east of Moscow).

“Mom, I’m Fine!”, Vladimir Safonov (1989).

“A Yawning Person”, Vadim Roklin (1969). With his avant-garde art, Vadim Rokhlin (1937 - 1985) opposed the state’s official socialist realism style. Unfortunately, success came to him only after he had passed away.

“The Queue”, Alexey Sundukov (1986). Long lines to buy any type of consumer product, which were always in short supply, were one of the hallmarks of Soviet life, and Sundukov was the first to portray this on canvas.

Untitled, Yulia Schuster (1968). Nothing to say here, just a face in the sky.

“Russia”, Sergey Shablavin (1992). A cybernetic physicist, Shablavin likes to experiment with angles, putting symmetric landscapes into geometrical shape. And the railroad is definitely something very Russian. So, this painting is a nice way to finish our list.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox