7 most famous Russian writers who migrated abroad

Between the 1917 revolution and the collapse of the USSR, more than two million people emigrated from Russia, mainly for political reasons. Among them were many artists, musicians, philosophers, scientists and, of course, writers, who did not want to put up with a totalitarian regime.

1. Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977), emigrated in 1919

Works to read: Mary; Invitation to a Beheading; Lolita; The Gift; Speak, Memory, and other stories

Nabokov's father was a politician and an opponent of the Bolsheviks, so when power was seized by the Soviets the whole family left Russia: they had no other choice.

First, Nabokov went to a college in England. Later, he lived in Continental Europe, but then he was forced to flee again – this time from the Nazis. For many years he lived in the U.S. where he gave lectures on Russian literature. Nabokov spent the last years of his life in Montreux, Switzerland, where he is buried.

Nabokov is perhaps the only writer on our list to have become equally famous both as a Russian and an American author. He wrote several of his early novels in Russian, but then he completely switched to English, in which he had been fluent since childhood. He also translated his own works.

2. Ivan Bunin (1870-1953), emigrated in 1920

Works to read: The Life of Arseniev, Light Breathing, Mitya's Love, short story collection - Dark Avenues

Bunin became famous at the turn of the century as a poet and author of short stories. He was also known as a translator of English poetry. In the 1910s, Bunin traveled a lot, visiting Europe, the Middle East and Egypt. He was bitterly opposed to the Bolshevik Revolution and turned his diaries depicting its aftermath into a book of memoirs called Cursed Days, which he published in emigration.

In 1920, Bunin left the country and went to Paris. He was in close contact with other Russian emigres and openly criticized the Soviet authorities. In France, he wrote his first big novel, The Life of Arseniev, and in 1933, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Later, the Soviet authorities invited Bunin to restore his Russian citizenship, but he refused. Like many Russian emigres living in Paris, he is buried in the Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Cemetery.

3. Gaito Gazdanov (1903-1971), emigrate

Works to read: An Evening with Claire, Night Roads, The Return of the Buddha

Gazdanov left his homeland at a fairly young age, although by then he had already fought against the Bolsheviks on the side of the White Army. He began to write in exile in France.

Gazdanov spent most of his life in Paris. At first, he lived in abject poverty, taking up any odd jobs and sometimes even sleeping on the street. At the same time, he managed to study at the Sorbonne. Even after he published his first and very successful book, An Evening with Claire, his financial circumstances remained constrained and he worked as a night taxi driver, using the experience as the basis for his new book, Night Roads.

Gazdanov asked Russia's main proletarian writer, Maxim Gorky, for assistance in securing his return back home. However, Gorky died and these plans did not materialize.

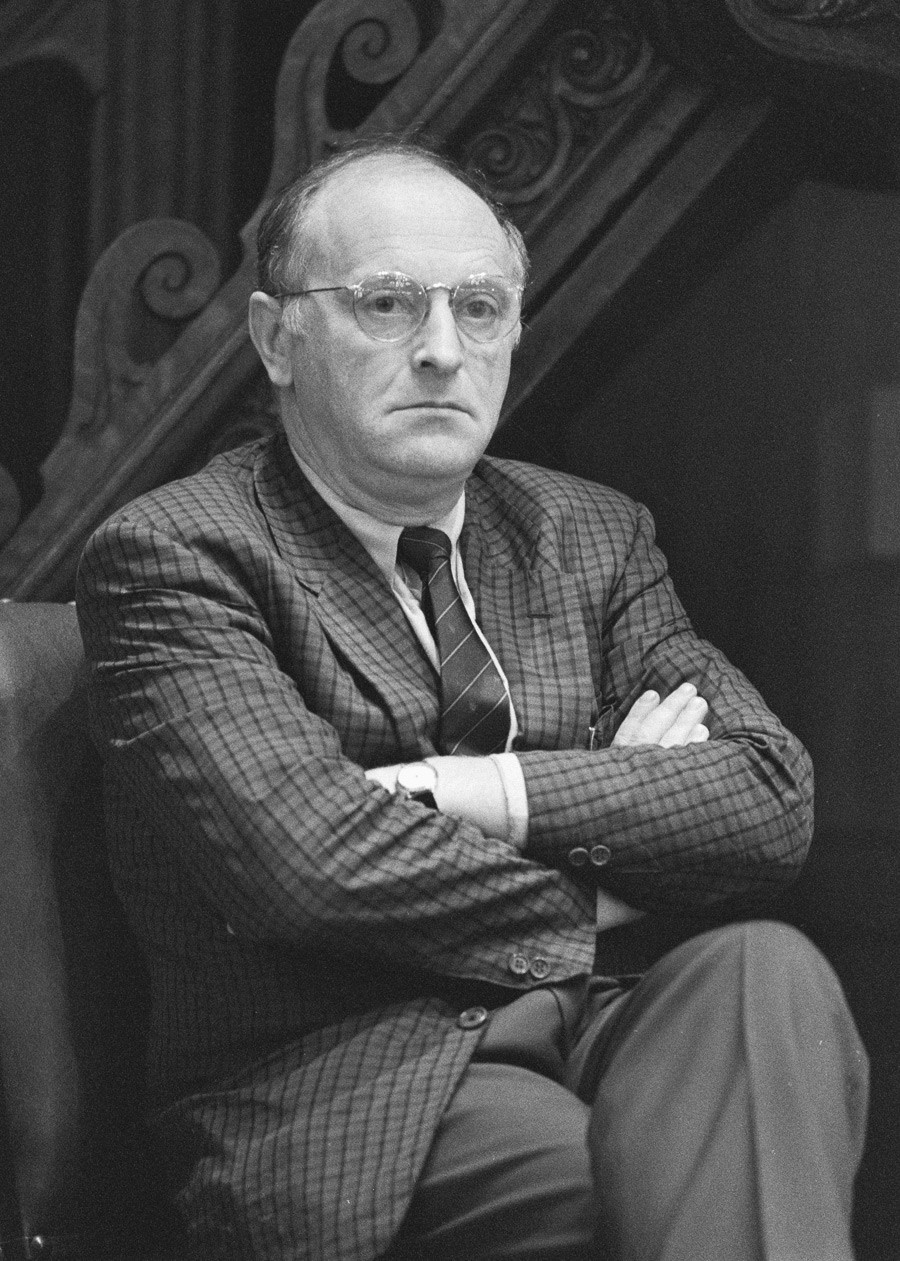

4. Joseph Brodsky (1940-1996), emigrated in 1972

Works to read: poetry, essays atermark, Less Than One

In the underground Soviet literature of the 1960s, he was a prominent poet who did not even have a secondary education. That was because Brodsky left school and went to work on geological expeditions and then in the morgue. However, for most of the time he did not have any employment, (which was a criminal offence in Soviet Russia), and he spent his time writing poetry. As a result, he served two years in prison for 'parasitism', and in 1972, with the help of publishers Carl and Ellendea Proffer, he emigrated to the United States.

Brodsky taught literature at the University of Michigan and tried to write poetry in English, which, however, did not quite work. Then he turned to the genre of the essay, and became famous in America as an essayist.

In 1987, Brodsky received the Nobel Prize in Literature. Although he refused to return to Russia even on a short visit, it was in his homeland that he became a real star and a symbol of an exiled poet who fights against the regime.

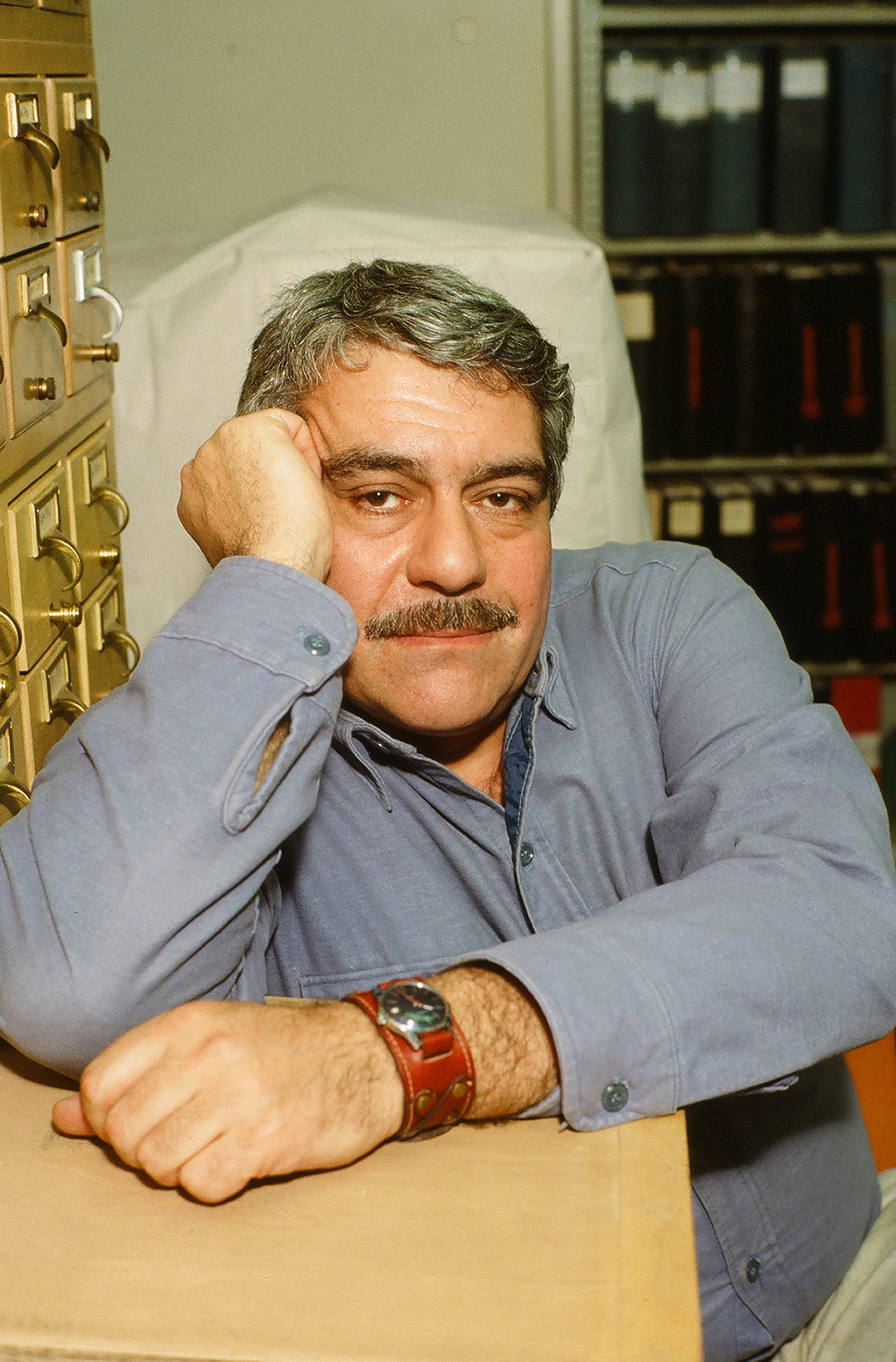

5. Sergei Dovlatov (1941-1990), emigrate

Works to read: The Zone, Pushkin Hills, The Compromise, The Suitcase

Dovlatov was one of the main Soviet humourists of his time. His stories are free of scathing satire, but are full of touching memories of the sometimes absurd life in the USSR. All his works are autobiographical: he described his experience of working as a prison warden and as a guide at the Pushkin Hills Museum, or of heavy drinking on journalistic trips.

Dovlatov's works were not published in the USSR because of his 'ideologically harmful' humor. In 1978, for disseminating samizdat he was asked to leave the country. He emigrated to the U.S. and settled in New York, where together with other Soviet journalists he published a newspaper, magazines and ran a radio in Russian. (His book, Affiliate, contains a jocular account of the émigré circles.)

Dovlatov died young, aged 48, and was buried in New York. His daughter, Ekaterina, managed to have a city street named after her father: Sergei Dovlatov Way. She also translates Dovlatov’s works into English.

6. Vasily Aksyonov (1932-2009), emigrate

Works to read: The Island of Crimea, The Moscow Saga, short stories

Aksyonov became a victim of the Soviet regime at an early age: his parents had been sentenced to 10 years in labor camps, and he himself was sent to an orphanage for children of prisoners. His mother, Eugenia Ginzburg, is the author of Journey into the Whirlwind, a memoir about Stalin’s purges that was turned into a 2009 film, Within the Whirlwind starring Emily Watson. He was later allowed to go to Magadan and live with his mother. Aksyonov depicted those years in his book, The Burn.

In the 1970s, Aksyonov was accused of anti-Soviet views and his novels were banned. In 1980, he was invited to the U.S. and he left, thus losing his Soviet citizenship. In the States, he read lectures on Russian literature and continued to write.

While in emigration, Aksyonov wrote a big novel about several generations of the same family against the backdrop of the first 30 years following the Bolshevik Revolution. The novel was a great success and was later turned into a TV series in Russia. In English it is known under the title, Generations of Winter, and is often compared to Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago.

Aksyonov was one of the few emigres to return to Russia after Perestroika. He divided his time between Russia and France. Aksyonov died and was buried in Moscow.

7. Sasha Sokolov (born in 1943), emigrated in 1976

Works to read: A School for Fools, Between Dog and Wolf, Palisandriia

This writer's life story reads like a spy thriller, although he now lives the life of a recluse in Canada. Sokolov was born in Ottawa, where his father was working either as a military attache or with the USSR Chamber of Commerce. Most likely he was a Soviet spy, which is why he was deported from Canada with his family.

Sokolov tried to flee the USSR when he was 19, but he was caught on the border with Iran. His father’s connections helped him avoid prison. Later, he worked as a journalist, and in 1975, he married an Austrian woman, which allowed him to leave the USSR.

A year later, he moved to the U.S., where Carl and Ellendea Proffer had just published his novel, A School for Fools, which Vladimir Nabokov, the No 1 on our list, was highly complimentary about. (In general, he was hardly ever complimentary about anyone).

Sokolov lived in the U.S., Canada, and Greece. He worked as a ski instructor and read lectures on literature. He visited Russia several times. In 2017, a documentary was made about him calledThe Last Russian Writer.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox