Russian-born novelist Vladimir Nabokov sits on a verandah overlooking Lake Geneva in his suite at the Montreux Palace Hotel, Switzerland (1965).

Getty ImagesMost people have read, seen the movie, or at least heard about Lolita, which chronicles an adult man’s love affair with a young girl. This controversial work brought Nabokov global success, but also closed off the Nobel Prize to him. There is much more to the writer than this work, though, and he lived a varied life that took him to many countries, as he fled first the Bolsheviks, then the Nazis. This overview highlights his key intellectual contributions.

At the age of 20, Nabokov left Russia with family, as his father had been engaged with politics during the time of the Russian Revolution – against the Bolsheviks. Nabokov was sent to study at Cambridge's Trinity College, where he founded the Slavonic Society, which was later reborn as the Cambridge University Russian Society. During this period Nabokov wrote poems in Russian and was produced the first translation of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland into Russian. As an interesting aside, Carroll wrote the novel after visiting St. Petersburg, where Nabokov was born.

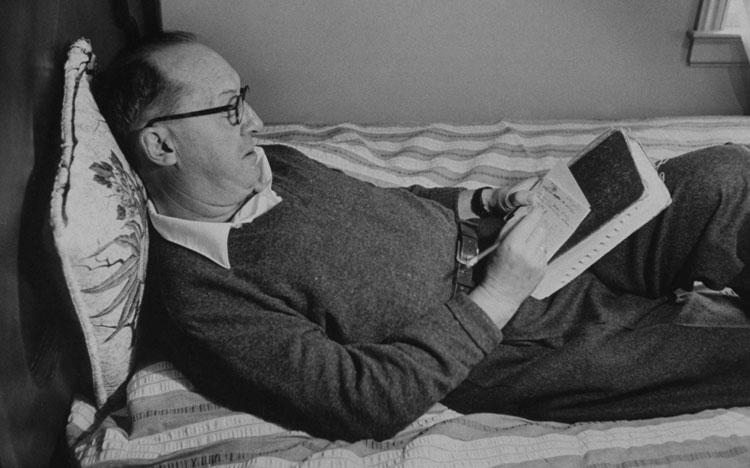

Nabokov began learning English before he learned Russian. Source: Getty Images/ Fotobank

Nabokov began learning English before he learned Russian. Source: Getty Images/ Fotobank

After studying in England, Nabokov moved to Berlin, where he married Vera Slonim. It was also where their son Dmitry was born, who went on to be heavily involved in preserving his father’s legacy, translating his novels and even bringing Nabokov’s unfinished work The Original of Laura to publication.

Because of his hasty exile, one of Nabokov’s leitmotifs is nostalgia. Some of his novels written in Russian while he was living in Europe explore the issue of homesickness, as well as shining a spotlight on the Russian émigré community in Berlin and Paris. Mashenka, The Defense, The Gift, Invitation to a Beheading and other works were published in Russian in Europe and were highly valued among émigrés. Although the works were not published in the Soviet Union until perestroika, they are now considered masterpieces in Russia too.

Nabokov’s novels reflect his intellectual depth; they show a spiritually rich man experiencing issues with the vulgarity of the external world. They are highly metaphysical, traveling between Nabokov’s imagination, real locations in Berlin, memories of his native country and the world of ordinary people.

Growing anti-Semitism led Nabokov to first leave Berlin for Paris, before fleeing Europe for the United States altogether in 1940. In America he lectured on Russian literature in universities, teaching at Wellesley College, where he founded the Russian Department, and then at Cornell University. Fredson Bowers published the full text of Nabokov’s lectures in English with an introduction by the author. They show Nabokov introducing Russia’s most important classic writers to an American audience, while also intellectually rethinking them. Among his subjects are Nikolai Gogol, Ivan Turgenev, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Leo Tolstoy, Anton Chekhov and Maxim Gorky.

Vladimir Nabokov standing with a butterfly net outdoors in the hills of Switzerland, circa 1975. Source: Getty Images

Vladimir Nabokov standing with a butterfly net outdoors in the hills of Switzerland, circa 1975. Source: Getty Images

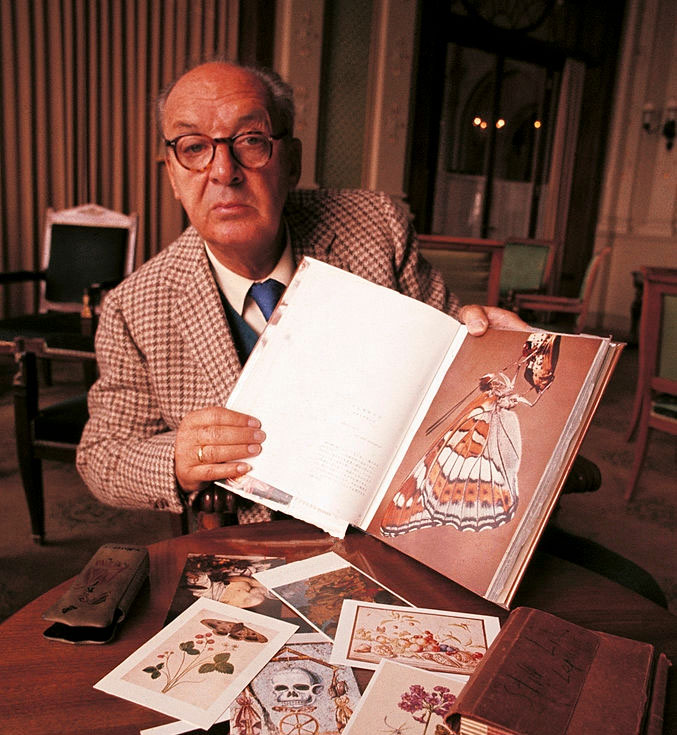

Besides working as a literature professor, Nabokov worked as the curator of the butterfly collection at Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. He was obsessed with butterflies and gathered a huge collection of them, which his wife Vera presented to the University of Lausanne after his death. He wrote more than 25 articles and pamphlets on lepidopterology and made up a new classification for the Polyommatus genus of butterflies. He mentions these insects about 570 times in his fiction.

There is even a butterfly genus Nabokovia named for Vladimir Nabokov. Source: wikipedia.org

There is even a butterfly genus Nabokovia named for Vladimir Nabokov. Source: wikipedia.org

There has been a great deal of research carried out on the subject of butterflies in his work, and literary critics suggest that certain butterflies depicted in Nabokov’s novels make allusions to real life. For example, in The Gift a yellow butterfly flies through locations in St. Petersburg that remind the author of his father, while in the autobiographical Other Shores the route of a swallowtail symbolizes the route that Nabokov’s grandfather – a revolutionary Decembrist – took on his way to exile in Siberia.

Alexander Pushkin’s novel-in-verse Eugene Onegin is one of the most challenging pieces for any Russian-English translator, due to its special strophes and rhyming structure. Nabokov decided not to follow Pushkin’s structure in his translation, saying that keeping the original rhyme and rhythm would kill Pushkin’s spirit and the work’s literary essence. Hence he translated the work into prose with a detailed two-volume commentary; this work has become fundamental to translators and researchers who are interested in Pushkin’s piece. Nabokov highly criticized his contemporary Walter Werner Arndt, who published his translation of Eugene Onegin a year earlier (in 1963), keeping the strophe structure and rhymes.

Besides Eugene Onegin, Nabokov translated Mikhail Lermontov’s classic novel A Hero of Our Time into English. He was also the first person to translate The Tale of Igor's Campaign, an epic poem about the 12th century that was purportedly written in the 15th century.

Another great work Nabokov wrote in English is his autobiography Speak, Memory, where he relates his childhood in a Russian noble family in St. Petersburg from 1903 onwards, and his emigration period up until 1940. There is also an earlier edition of memoirs published in Russian called Other Shores.

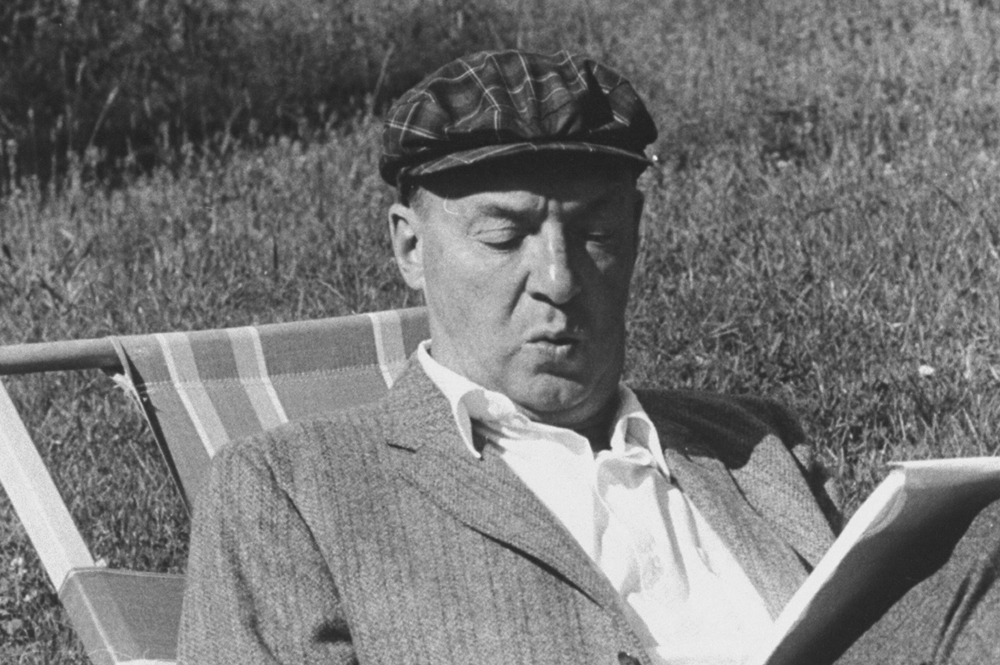

Vladimir Nabokov writing on paper in the garden. Source: Getty Images

Vladimir Nabokov writing on paper in the garden. Source: Getty Images

As is perhaps already clear, Nabokov was a highly intelligent man who combined both scientific and linguistic abilities. He was genuinely trilingual, once commenting “my head says English, my heart, Russian, my ear, French”, and applied these skills to writing, teaching, and translating. He also had synesthesia, which manifested itself as seeing music and having a specific feeling about the color of certain sounds and letters. This condition is quite rare – with Isaac Newton, Goethe and Carl Jung the only other intellectuals to experience it.

Another curious fact about Nabokov is that he wrote his novels on index cards. He had thousands of them, and only he could understand their order and meaning. When his son published The Original of Laura, he took it upon himself to assemble these cards, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, there are many critics who disagree with his choices.

Nabokov was also a fan of chess and would make up chess problems. Several of his novels mention chess or have a chess motif in them, most notably The Defense, which has a chess grandmaster as its main character.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox