3 reasons to read ‘Woe from Wit’, Russia’s best comedy in verse

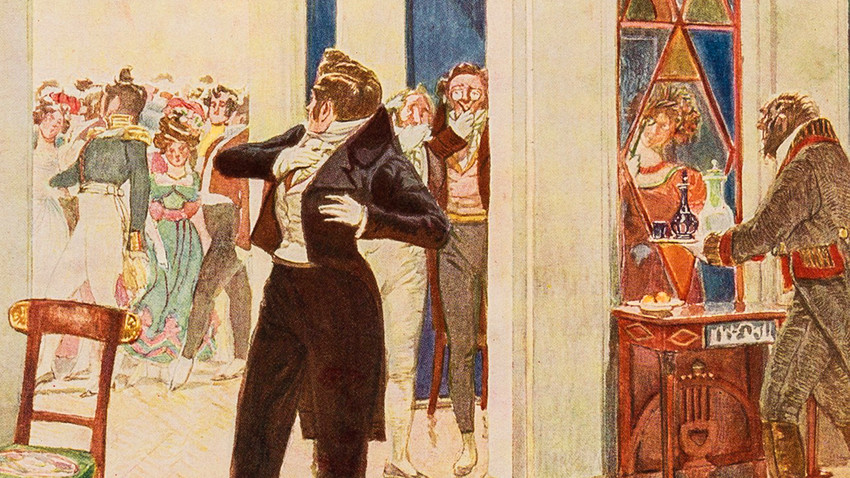

Illustration to the comedy Woe from Wit by Alexander Griboyedov, 1913.

Getty ImagesWoe from Wit, a comedy play by Alexander Griboedov, is a part of the Russian school curriculum and is read by every student across the country. While frequently staged in theaters across Russia, for some reason it is not well-known in the English-speaking world. However, we are sure that if you read it then you’ll certainly appreciate its brilliance. You won’t regret it!

1. It revolutionized Russian drama

Illustration for 'Woe from Wit'

Dmitry Kardovsky/Олма Медиа Групп, 2015Woe from Wit brings readers to Moscow of the early 19th century, right after the end of the war with Napoleonic France. Young noble men started to study abroad in Europe, and author Griboedov shows one of these ‘new’ men, Alexander Chatsky, who had already embraced the European values instead of the traditional values of older Russians.

He has a sense of duty and honor, but he doesn’t want to serve his country as a slave; he wants his own freedom and sense of dignity to be respected. With such a character Romanticism first appears in Russian literature, and this theme frequently translates into confrontation between one smart progressive man and the masses. Later, this type of character was developed by Alexander Pushkin in Eugene Onegin, by Mikhail Lermontov in Hero of Our Time, and even in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment.

Men such as Chatsky later created secret societies and plotted the Decembrist Uprising of 1825, when noblemen called for a Constitution and limits on autocracy in Russia.

2. The most quoted Russian book

Nearly a dozen phrases from the play are still widely used by Russians today in conversation, and many don’t realize that the roots of these aphorisms are in 19th-century comedy. Here are some of the most popular ones:

- “And who are the judges?”

An extremely apt rhetorical question, meaning that before judging anyone, a man should take a look at himself! The ‘judges’ in the play represent the older generation with their outdated views. Should one follow their advice or don’t heed their opinion? A young progressive man is sure of the answer - No, do not pay attention to them.

Alexander Chatsky, illustration by P.Sokolov

'Obshestvennaya polza' publications, 1866- “No one happy minds the clock”

A noble young woman spent the night with her beloved one, and lost track of time. While her father was looking and asking for her, the maid had to make up excuses so that the father didn’t find out the truth. When the young lady finally came out of her room, the maid was angry that she was so late, but the young woman only said: “No one happy minds the clock”. We all know this is true. Haven’t you ever noticed that time spent with your beloved passes extremely quickly?

Theater staging of 'Woe from Wit,' 1977: Sofia and her maid

Roman Vorobyev/youtube.com- “My carriage! Bring my carriage round!”

The main character, Chatsky, was extremely mad at everyone, and finally he finds his beloved, Sofia, with a new boyfriend! He is fed up with people lying and deceiving each other, and the fact that they judge each other harshly (remember, “And who are the judges?”). So, he decides to flee as soon as possible - and not only from his home, but from Moscow and to also leave the country. So, if you want to show that you’re entirely fed up with a situation and want to get away from it all, you can say “My carriage! Bring my carriage round!” (or in Russian “Карету мне, карету” - ‘Karetu mne, karetu’).

Theater staging of 'Woe from Wit,' 1977: Alexander Chatsky

Roman Vorobyev/youtube.com3. A brand new translation

Columbia University Press recently published a new translation of Griboedov’s Woe from Wit, as part of their project ‘Russian Library’. Translator and poet, Betsy Hulick, felt there are no existing translations in verse that can be either acted or read with ease or pleasure. “You have to plough your way through them,” she said.

So, Betsy decided to do something about this and to make the 19th century comedy easier to understand for the English-speaking audience. “Betsy Hulick’s translation is accurate, sprightly, inventive, and eminently playable. She has captured the sharp characterizations and aphoristic dialogue of the original," says Laurence Senelick, professor of Tufts University's Department of Theatre, Dance, and Performance Studies.

As an actress herself, Betsy would be happy if Woe from Wit would be staged in the U.S. theaters. However, it’s unlikely that Broadway will produce a play that has over 20 characters. According to Betsy, “One man up against all the prejudice and bigotry of the age is not an insignificant theme.”

‘Russian Library’ series editor Christine Dunbar says she would argue that Woe from Wit is not only still topical, but moreover, it’s fun! And she thinks that the goal is to show this other side of Russian literature.

“Most U.S. readers think of Russian literature as heavy and serious - important literature, for sure, but maybe not something you would read for fun,” she says. “Woe from Wit is witty and snarky and absolutely fun, even as Griboedov is making a larger point about a society that seems to prefer juicy gossip to the truth,” Christine adds.

So why do you still hesitate to read it?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox