The Tretyakov Gallery’s 7 most scandalous paintings

The paintings were originally bought by the prominent gallery’s founder, Pavel Tretyakov, who had incredible artistic intuition and was exclusively guided by his own taste. Since his gallery was public, Tretyakov had to take into account the censors’ strict guidelines - some paintings were not only rejected but were entirely banned from display. Thanks to Tretyakov's efforts, however, they survived, and today it’s impossible to imagine the leading repository of Russian art without them.

1. Vasily Perov. Easter Procession in a Village (1861)

Vasily Perov was one of the founders of the association of Peredvizhniki artists (known in English as the “Wanderers” or “Itinerants”). He eschewed high society subjects and instead depicted the everyday lives of ordinary people. His well-known painting, Troika, shows poor children pulling a barrel of water. Perov was a celebrated artist but his Easter Procession in a Village caused an uproar. Above all, the public was upset that the artist depicted the celebration of Easter as a drunken procession - the peasants half-closed intoxicated eyes, the tipsy priest squashing an Easter egg under his foot, and drunks lying around beside the church doors. In St. Petersburg, the picture was withdrawn from exhibition and the artist accused of immorality. Pavel Tretyakov, however, despite attempts to dissuade him, still acquired the painting.

2. Vasily Vereshchagin. The Apotheosis of War (1871)

Vereshchagin travelled extensively in Central Asia and painted many canvases. This painting, however, became his most famous. Initially, it was titled The Triumph of Tamerlane and referred to a legend about the soldiers of the famous Mongol military leader who made pyramids from the skulls of decapitated enemies. The sight of the skulls, as well as the scorched, desolate desert and the city lying in ruins in the background shocked the genteel St. Petersburg public. Vereshchagin dedicated his painting to "all great conquerors - past, present and future".

3. Ivan Kramskoi. Christ in the Desert (1872)

The life of Christ was a popular subject with 19th century artists, but Jesus was usually portrayed as serene and inspirational, and never as emaciated and lonely in the middle of the wilderness. Kramskoi's canvas depicts the temptation of Christ by the devil during his 40-day fast after being baptized. His image is extremely human and attention is drawn not just to the strained facial expression but also the intertwined fingers of clasped hands. Eyewitnesses recalled how at the exhibition the painting split public opinion. Some were struck by its profundity and portrayal of suffering, while others expressed indignation at what they saw as "blasphemy" and the desecration of something sacred. Kramskoi himself recalled that people accosted him and asked why he depicted Christ in that manner. In despair, the artist defiantly retorted that they hadn’t seen him either. As for Pavel Tretyakov, he immediately bought the controversial painting and regarded it as one of his collection’s most powerful art works.

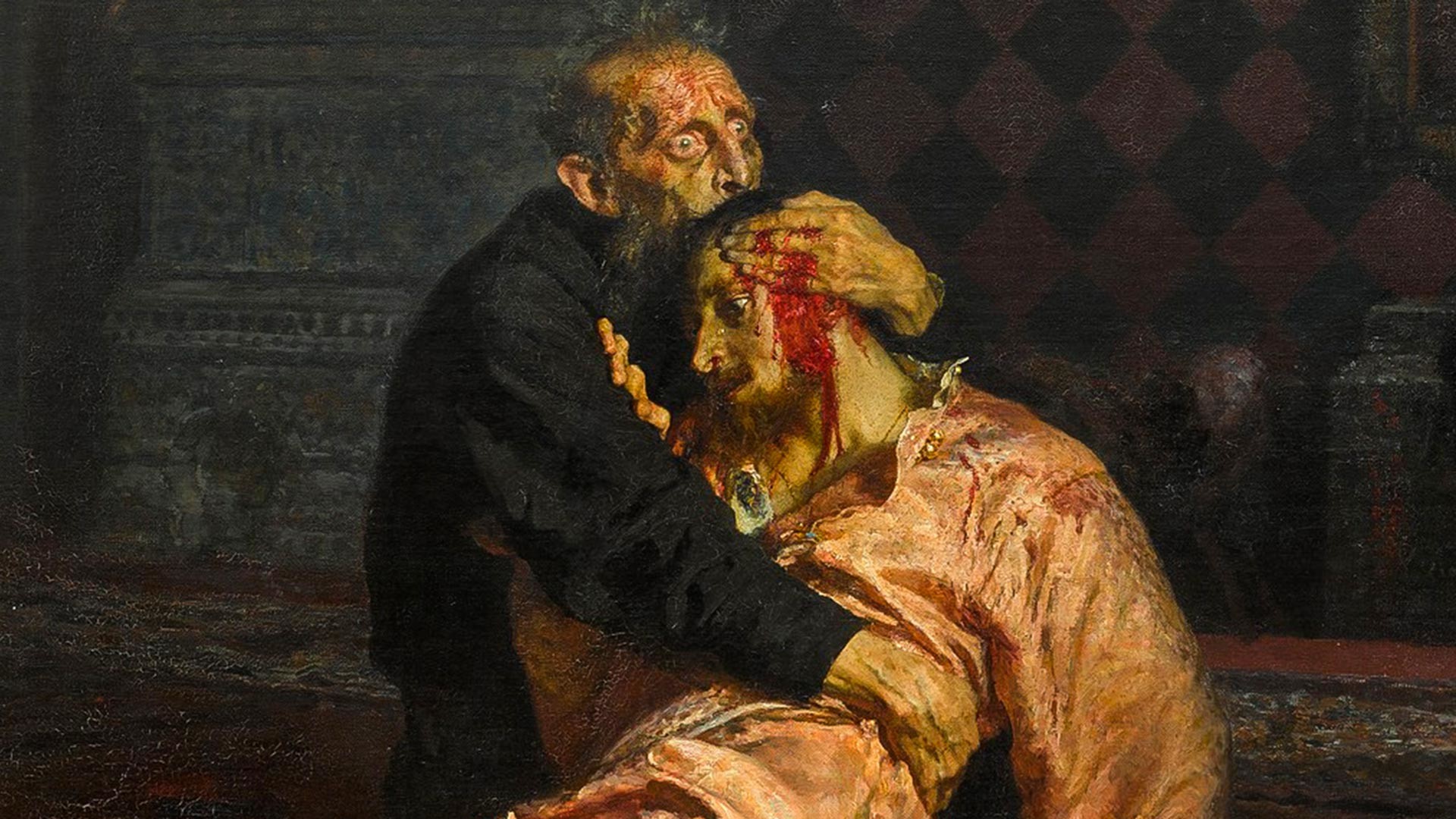

4. Ilya Repin. Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on 16 November 1581 (1883-1885)

This painting still provokes great emotion. In 2018, a vandal who didn't like its "mendacious" content seriously damaged the picture. Historians often dismiss the myth that Ivan the Terrible murdered his son, but it was Repin's scene - one of the first such bloody paintings based on a pseudo-historical story - that left an indelible mark on the popular imagination. Repin painted the canvas with the assassination of Emperor Alexander II fresh in his mind. Initially, he showed it to his fellow artists, who were stunned - everyone recognized his incredible talent. However, Emperor Alexander III didn't like the painting and the state ideologist Konstantin Pobedonostsev called it repulsive. The picture was bought by Tretyakov but the Tsarist censors banned it from display. The ban, of course, was later lifted.

5. Vasily Surikov. Boyarina Morozova (1887)

Surikov's monumental canvas deals with the 17th century split in the Russian Orthodox Church, and shows the scene of the arrest of Boyarina Morozova, an Old Believer who refused to make the sign of the cross with three fingers as required by the Church reform. The painting made a strong impression on the public as a successful experiment in a subject drawn from Russian history. Many people praised the skilful way in which Old Russia was authentically recreated, and also the depiction of a Russian (and a woman, at that!) as someone strong in spirit and unbroken by suffering. But the painting also had a multitude of critics who complained of faulty composition, wrong proportions, mistakes in gestures and the placing of people's arms and other details. Some even said the picture was more like a tasteless variegated carpet than a painting.

6. Arkhip Kuindzhi. The Birch Grove (1879)

What could possibly be controversial about a painting of a birch grove? In fact, the picture was surrounded by controversy: Kuindzhi was late finishing the work for an exhibition by the Wanderers group of artists in St Petersburg, causing the opening to be delayed, much to the chagrin of the other artists. In the end, the picture appeared on the walls two days after the inauguration. Viewers were full of admiration for its amazing play of light and shade, even suspecting Kuindzhi of some sort of ingenious optical trick and believing it to be specially illuminated with a light from behind. One critic savaged the painting, however, writing that the colors were unnatural and that the trees stood around like stage props and were arranged unnaturally and that they seemed to be "smeared with some muddy green coloration". The critic turned out to be one of the Wanderers, hiding behind a pseudonym. Kuindzhi was so offended that he left the Wanderers group - and The Birch Grove was thus the last work he displayed at their exhibitions. Naturally, it was eventually purchased by Tretyakov.

7. Mikhail Vrubel. Princess of Dreams (1896)

This painting’s story reads like an adventure novel. The panel was commissioned by art collector and patron Savva Mamontov for the arts pavilion of the All-Russian Industrial and Art Exhibition in Nizhny Novgorod. Vrubel at this time was still unknown. A theater production based on Edmond Rostand's play, La Princesse lointaine [The Princess Far Away], had recently premiered in Russia, but Mamontov hadn’t cleared the work with the Academy of Arts that was "hosting" the pavilion. On viewing the work, an Academy jury ordered it to be taken down, and a proper hullabaloo erupted, word of which even reached Emperor Nicholas II. The latter ruled that the Academy's wishes must be respected (even though in the future the Tsar was to express admiration for Vrubel).

A compromise was finally reached and the work was completed by well-known artist Vasily Polenov on Vrubel's behalf. Even though the panel itself was not put on display in the pavilion, Mamontov brought a large number of other paintings by Vrubel to the exhibition, and also organized a stage production for which Vrubel was set designer.

Those who had the chance to view the work were divided. Some admired its innovation, but others criticized the ugliness of the "decadent panels". Writer Maxim Gorky sweepingly pronounced that this "monstrosity" signified a "destitution of spirit and poverty of imagination". Eventually Mamontov was to make a majolica copy of the panel at his factory. It now adorns the facade of the Hotel Metropol in the very center of Moscow.

The panel ended up in Mamontov's private opera and was later transferred to the Bolshoi Theater, in the storerooms of which it was discovered in the mid-20th century and then moved to the Tretyakov Gallery, where it only went on display in 2007. A whole room devoted to Vrubel was opened and the building had to be specially adapted to accommodate the huge masterpiece.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox